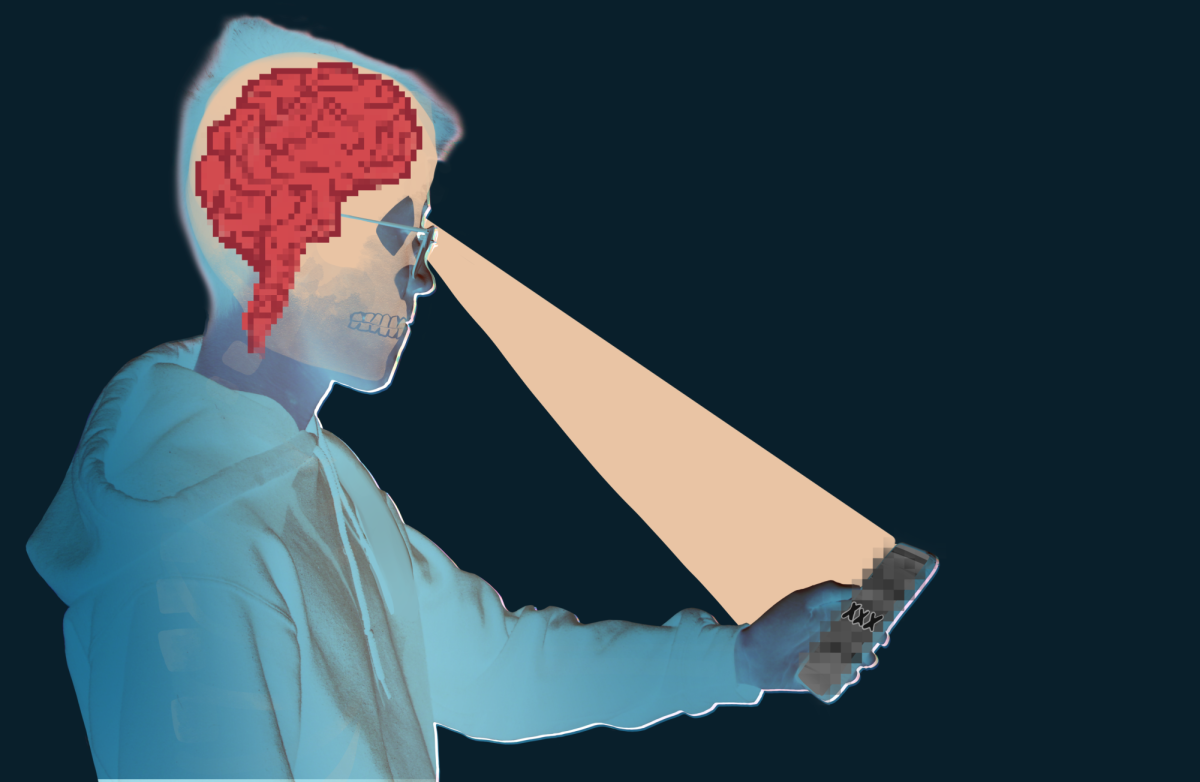

Flipping through my peers’ Instagram Stories, I’m bombarded with infographic after infographic. From climate change to overseas conflicts, each post presents new information explaining what’s wrong with the world and why. Yet, as the posts keep rolling in, I can’t help but wonder how my classmates’ are internalizing so much information within minutes. Are these all issues that they’re actively attempting to research and fight for? Or are these reposts just there to make the poster look like they’re doing so? And at the same time, I wonder, am I not posting enough?

The spreading of these posts can be seen as performative activism, an issue especially prevalent among teens.

Performative activism is activism done out of a desire to make oneself look better, rather than a desire to help the cause being promoted. As silence during world events is becoming increasingly frowned upon, some teenagers put pressure on each other to speak out, and others are desperate to prove to their peers that they care. Although youth activism is incredibly important, when said activism comes from a performative place, it can cause more harm than good.

Activism among youth is undoubtedly essential. Although a lot of people see it as pointless, teenagers’ collective push to educate the masses on world issues has a real impact. I’ve seen a massive change in public perspective regarding issues like systemic racism because of dialogues amplified by young people.

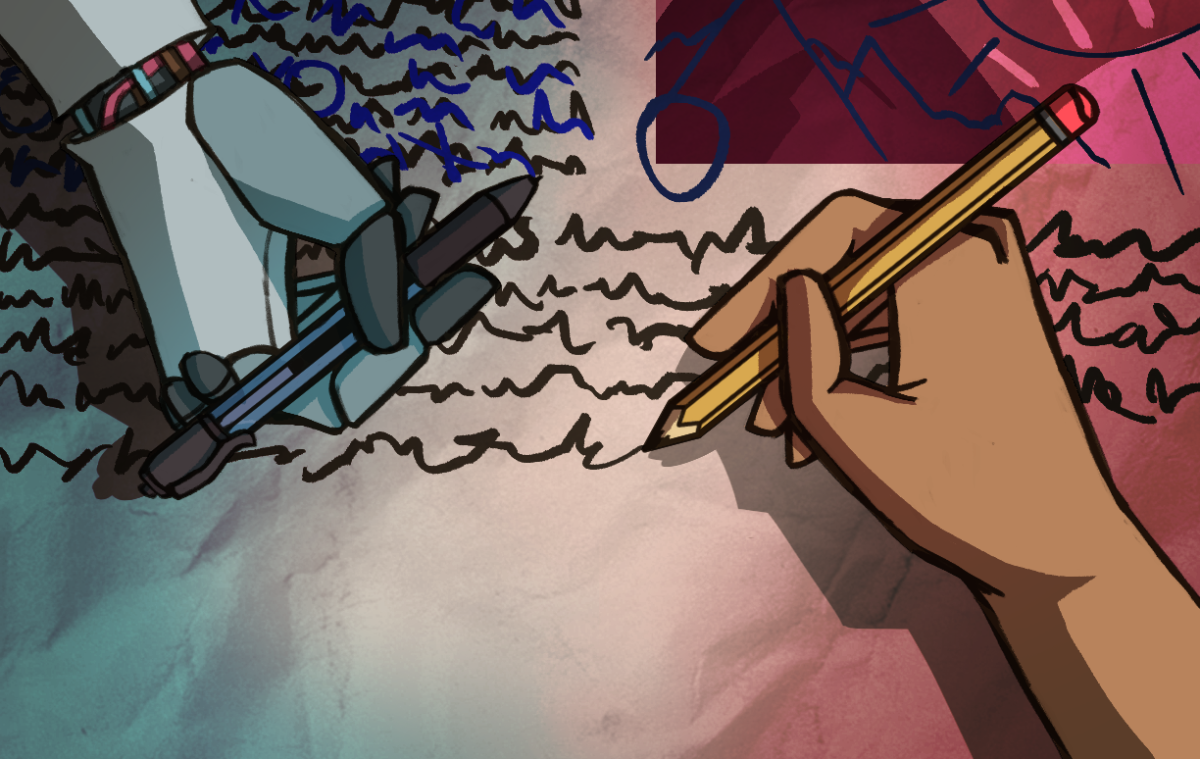

However, when teens put pressure on each other to be activists, many feel the need to look informed and involved in fighting major issues, even if they aren’t willing to put in the effort to do so. As a result, a lot of teenage activism is performative, and revolves more around looking like an activist than actually fighting for a cause. Much of this involves the spread of infographics. This easy-to-digest format leads to performative activists spreading and absorbing only surface level and one-sided information, which oversimplifies nuanced issues in harmful ways.

One famous example of performative activism revolved around Blackout Tuesday in June 2020. After the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer, millions of Instagram users posted black squares with the hashtag “#blackouttuesday,” refrained from posting unrelated posts, and encouraged others to do the same. I saw my peers putting heavy pressure on others to join the movement, and even scorning people who didn’t. Because of the influx of people pressured into making posts despite not fully understanding the situation, many people mistakenly posted black squares under other activist hashtags such as “#blacklivesmatter,” which was being used to spread information. This led to actual Black voices and important updates being drowned out by posts made solely due to pressure and not to the benefit of any movement.

The effects of performative activism can be seen in some ongoing boycotts against Israel. In the past few weeks, I’ve seen many different posts spreading through my classmates’ Instagram Stories, all listing different companies to boycott. Each list seems to grow longer than the last. However, major boycott organizers such as the ones behind the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement (BDS) are against these lists. BDS claims on their website that only certain companies should be targeted at a time for maximum impact. Though their intentions were good, when teens repost these boycott lists without doing any outside research, they are actively harming larger movements across the country.

Because the creators of these posts do not have to comply with any reliability rules or guidelines, misinformation can spread easily. I saw dozens of sensible people repost an infographic denying a commonly accepted genocide overseas solely because it was written from an angle that made it seem like the activist thing to do. The post blamed racism and American propaganda for making the world see the actions of their country as genocidal, and despite those claims not holding any weight, they matched the voice shared amongst activists and were, therefore, considered true. A few days later, the inevitable callout post on the infographic began to spread, and despite many reposting it, nobody stopped to rethink what they were doing. This allowed them to accidentally promote genocide denial in the first place.

I myself am definitely not exempt from spreading questionable information to help my image. Because I saw so many of my peers posting opinionated infographics as if they were fact, I felt like taking the time to research was counterproductive. People were speaking about injustice now, at this very moment, and I didn’t want to miss that window just because I doubted some post. The sheer amount of issues being discussed added to this pressure; if I took the time to look deeply into every single thing I stood for, it would take months. Whenever I saw an infographic at the peak of my performative activism, my first instinct wasn’t to see if it was true, it was to see if it fit the “activist” worldview I felt pressured to maintain.

When teens are spoon fed infographics and news solely from other activists, their views are never challenged, leading to little room for discussion and a less nuanced understanding of major issues. People have their own opinions echoed back to them tenfold, and those with opposing perspectives are alienated, even when their overarching views are largely the same. Yelling at people with differing views is an easy way for someone to feel like they’re making a change without putting in any work or questioning their own actions.

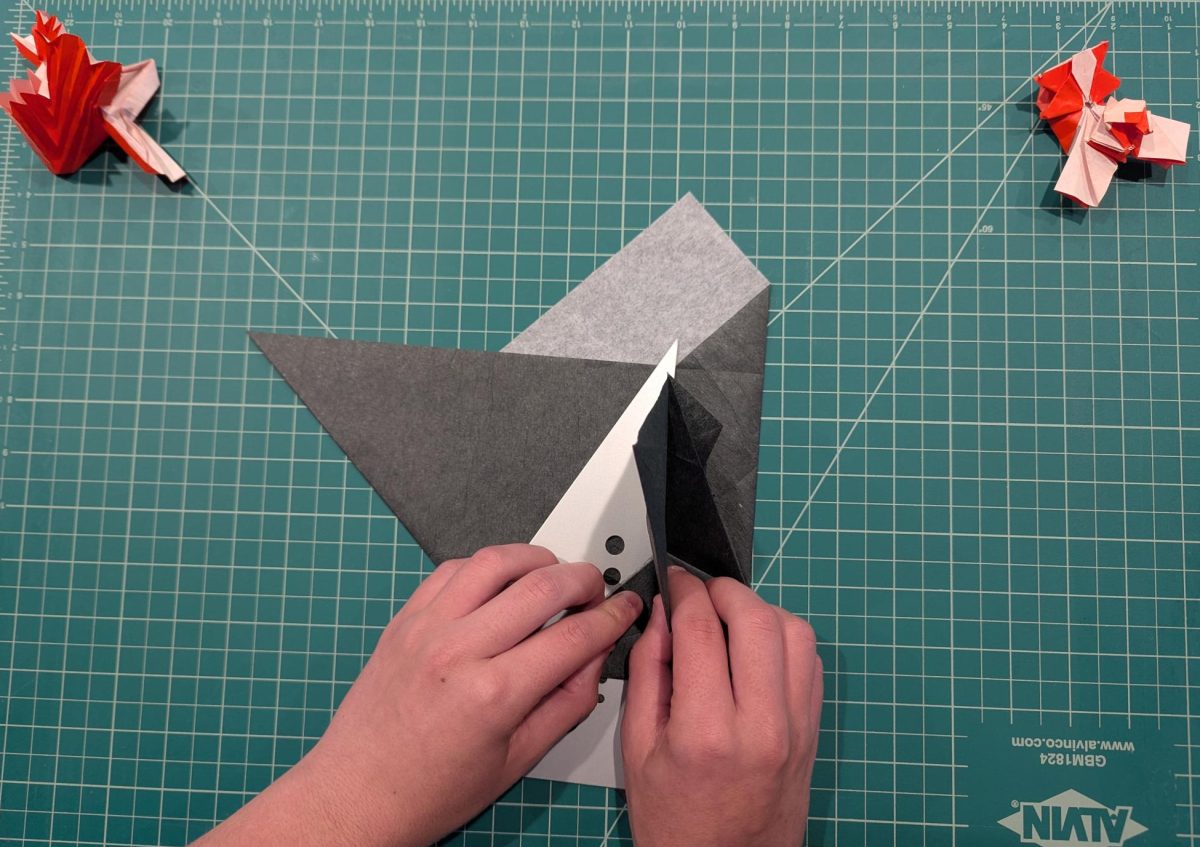

Although the value of teenage activism can’t be overstated, it must go beyond simple and performative actions. While resources like infographics can be helpful in learning about global issues, it’s important that teens, including myself, consult multiple sources and perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of the issues they fight. Once they eliminate the pressure to look like activists and focus on actually being ones, teens can use their voices to much greater effects.