For the past five blocks, senior Annie Li has avoided looking over their shoulder. Even without looking, however, Li can feel the eyes digging into their back and can hear the footsteps of the man following them. Clutching their phone and bag with a tight grip, Li hurries into the nearest Walgreens, hoping to find safety in the crowded store.

This isn’t Li’s first time being followed home, and while not all Lowell students can relate to being followed on the street, concerns regarding safety in San Francisco are shared by many.

An increasing number of Lowell students feel unsafe in San Francisco, despite declining violent crime rate. An internal poll has found the perceived threat to Lowell students’ safety has intensified. However, whether students are directly impacted by crime or not, the media emphasis on issues like homelessness, cleanliness, and public safety have contributed significantly to this heightened sense of fear. The impact of crime extends beyond some Lowell students’ immediate fear, affecting their mental and physical health. While building a sense of community and getting professional help may relieve the negative effects of crime, Lowell students are still affected by it every day.

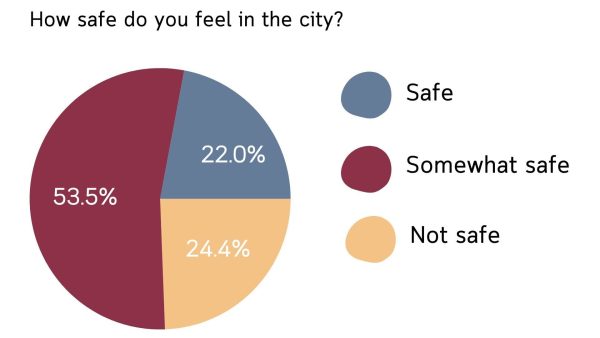

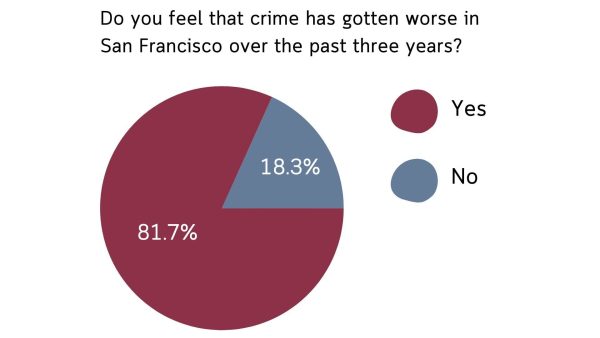

Since the pandemic, San Francisco has gained a reputation for having an excessively high crime rate, despite a downward trend in the amount of violent crime. While violent crime rates are down by as much as 25 percent since 2006, many San Francisco residents feel increasingly unsafe. According to a 2023 survey by the City and County of San Francisco, 63 percent of San Francisco residents feel safe while outside in their neighborhoods during the day and 36 percent feel safe at night, decreasing from 85 percent and 53 percent, respectively, in 2019. Although neighborhoods with lower SES like the Western Addition and Visitacion Valley have higher crime rates, the poll by the City found high safety concerns in more affluent areas as well. However, according to the City poll, Nob Hill was rated only slightly safer than Visitacion Valley. An internal survey conducted by The Lowell found that out of 125 students, 81.6 percent of students feel like crime in the city has gotten worse over the past three years.

The disconnect between declining crime rates and heightened feelings of unsafety can be attributed to preconceived opinions on public concerns such as homelessness or cleanliness. According to Dr. John Boman, an associate professor at Bowling Green State University, this discrepancy between crime rates and feelings of unsafety cannot be solely explained by direct victimization, where students themselves have had crimes committed against them, but by vicarious victimization. Boman describes vicarious victimization as witnessing a crime or having a preconceived perception of disorder, as opposed to being directly affected by it. Many San Francisco residents believe homelessness, cleanliness, and public safety are among the city’s top issues. According to Boman, while homelessness and cleanliness don’t explicitly translate to crime, public concern over those issues are examples of such perceptions of disorder. “The fear is that this is some type of criminal behavior, and that fear can transform your perception of ‘I feel unsafe,’” Boman said. “The fear of crime is certainly something that can change, irrespective of what crime is actually doing in a population.”

Areas residing lower socioeconomic status (SES) individuals tend to experience heightened issues related to homelessness, drug use, and crime, contributing to the prevailing negative perceptions of unsafety. Owen Gallupe, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo, who collaborated with Boman on a 2020 study researching crime rates after the beginning of the pandemic, stated that because neighborhoods with lower SES tend to have more problems with homelessness, drug use, and crime, negative feelings of unsafety exacerbates. “Those things are a visual sign that things are not going well, so whether that’s true or not, that’s how people internalize it,” Gallupe said.

While students like senior Brandon Liu have never been directly affected by crime, Liu has experienced vicarious victimization, contributing to increased concerns about his safety. As a Western Addition resident, Liu is surrounded by higher rates of homelessness and crime, adding to an overall perception of disorder. “It’s very chaotic,” Liu said. “There are a lot of car accidents and there’s a lot of homelessness around my area. Generally, I feel safe inside my home, but there are some times when it just feels sketchy.” Although he drives to school now, he’d notice altercations between other people on the street while walking to the bus. “I had to be more aware of my surroundings and just make sure I wasn’t holding anything valuable or make sure that there was like nothing that could be easily taken,” Liu said. “No one’s actually approached me before, but I do know it’s dangerous because I’ve seen what people can do.”

Li has been followed home on MUNI on multiple occasions, including a time when a man tried making physical advances on them. “I was on the M bus just sitting alone, and then some random guy just came over and tried to put his arm around me,” Li said. “I ran up to the bus driver and the guy just stayed in the back looking at me. It wasn’t even my stop to get off, but I got off immediately.” This wasn’t an isolated event, however. Li remembers walking away from a man at a MUNI stop, only to look back a block later to see him following them. “I thought that, maybe, it’s all in my head and I’m not actually being followed, but four blocks later, I’m speed walking and he’s still following me,” Li said. Something that bothered Li particularly was the fact that those incidents occurred in broad daylight. “Those things didn’t happen at night, where I normally would expect it to happen. It’s really concerning because you don’t know where and when something can happen to you,” Li said. “I’ve been more paranoid about safety. You never know what might happen.”

While experiences like Li’s may seem characteristic of neighborhoods with lower SES, Lowell students who live in upscale neighborhoods are feeling unsafe. Senior Tomás la Sala lives between Russian and Nob Hill, areas that are typically seen as safer. According to la Sala, however, crime and feelings of unsafety aren’t uncommon in his neighborhood. Coming back from football practice one night, la Sala discovered his house had been broken into, and his family had valuables stolen from them. This incident increased his concern about safety in the neighborhood; La Sala has become more wary of what happens in his neighborhood, recalling gunshots, car break-ins, and most recently, someone stealing the Christmas wreaths from every door on his block. “Some nights if I hear footsteps outside – or I’ll even imagine footsteps downstairs of people in the basement – I think someone could break in again, and if someone is in the house, hurt them,” la Sala said. “You’re kind of like a victim in your own neighborhood and you’re scared to live a regular life.”

According to Brooke Wollet, a Ph.D. criminology student, victimization, whether direct or vicarious, renders a plethora of negative health effects, including high blood pressure, PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Wollet and Dr. Boman explained that while direct victimization – such as being mugged or assaulted – leads to significantly worse mental effects than vicarious victimization, the effects of both have implications on physical health as well. “High levels of anxiety, depression, [and] PTSD, are not conducive to living a high-quality physical life if they are left untreated,” Boman said. “Because of [those effects], blood pressure goes up. When blood pressure goes up, lifespan goes down.” According to Professor Gallupe, these effects on mental health also negatively affect social interactions, specifically among teenagers. “The teenage years are when peers are most important,” Gallupe said. “Being victimized can make them more anxious, more depressed and those changes in the brain can manifest themselves in personal relationships, where people have a harder time being around others.”

According to Boman, one way for people to alleviate feelings of unsafety is to look at real data, such as statistics from the San Francisco Police Department, as opposed to relying on inflated media coverage. However, Boman noted flaws in this method, one being that not all crimes are reported, and two, that the average person prefers to have data presented to them through the news or social media, instead of digging online for more reflective trends and numerical evidence.

Students like la Sala have found a balance between real numbers and easily accessible news. La Sala uses an app called Nextdoor, which serves as a place where people who live in a neighborhood can buy and sell items, send messages, and alert each other about crimes in the area. La Sala sees the app as a way to reinforce a feeling of community and awareness within his neighborhood which is what Boman attributes as a way for populations and individuals to mitigate feelings of unsafety. Boman labeled it as collective efficacy, an idea that community members work together in looking out for their neighbors to achieve a tighter-knit environment. “I’m talking about a real sense of belonging in a place,” Boman said. “That is a huge thing that impacts not only crime and victimization but also perceptions of safety. If that is present in a neighborhood, the crime rate drops, the victimization rate thus drops, so everything gets better, even real estate value.”

However, Boman stated that for structurally disadvantaged and lower SES neighborhoods, developing collective efficacy is often difficult. According to him, higher crime rates and lower SES in such neighborhoods cause a higher likelihood of residents wanting to move out. Gallupe says that lower SES areas may work backward in terms of collective efficacy, considering turnover and crime rate. “If there’s a lot of crime in an area, then that might cause people to be less willing to look out for others in that area,” Gallupe said. “If they’re scared for their own safety, then they may not step in if they see something. That essentially sends a message that there are not people looking out for other people in the community, and that can be a green light for crime to occur.”

Li feels that the sense of safety they felt in their neighborhood has disintegrated since their

childhood years, largely due to an increasing fear of crime. “The streets were a lot livelier,” Li said. “You would feel a sense of community, but now, it’s like you’re too busy worrying about other things to feel safe in them,” Li said. “Sometimes at night, you’ll hear very questionable beeping noises and the occasional gunshot. Everywhere you go there is a lot of homelessness and drugs.”

Liu tries to keep in mind that disorder in the city doesn’t necessarily relate to crime. To him, San Francisco’s rising drug and homeless population doesn’t help combat the negative perceptions of it, and for some students, crime is just a hard truth they must live with. “Not all the people on the street are hard drug addicts,” Liu said. “For those people and on a wide scale, to help them is more political. It would come down to the city.” La Sala agrees, stating that crime is something that citizens have to accept, regardless of socioeconomic standing. “It’s upsetting that we have to accept it, but at the same time, there are advantages that city life brings that tie into the nature of crime, like the density of people, stores, and businesses,” he said. “San Francisco has its positives, things like diversity, but it also has crime. It’s just a shame that we have to think of our city in such a negative way.”

John J Donohue • Dec 23, 2023 at 3:51 pm

As always, Roman contacted a number of different sources, both Lowell students and professionals to create a great look at what worries many in SF. I may miss the first baseball preseason game because Oakland is a lot worse with no police chief and a police force late to the call. —John Donohue, Retired Lowell faculty 1983-2015