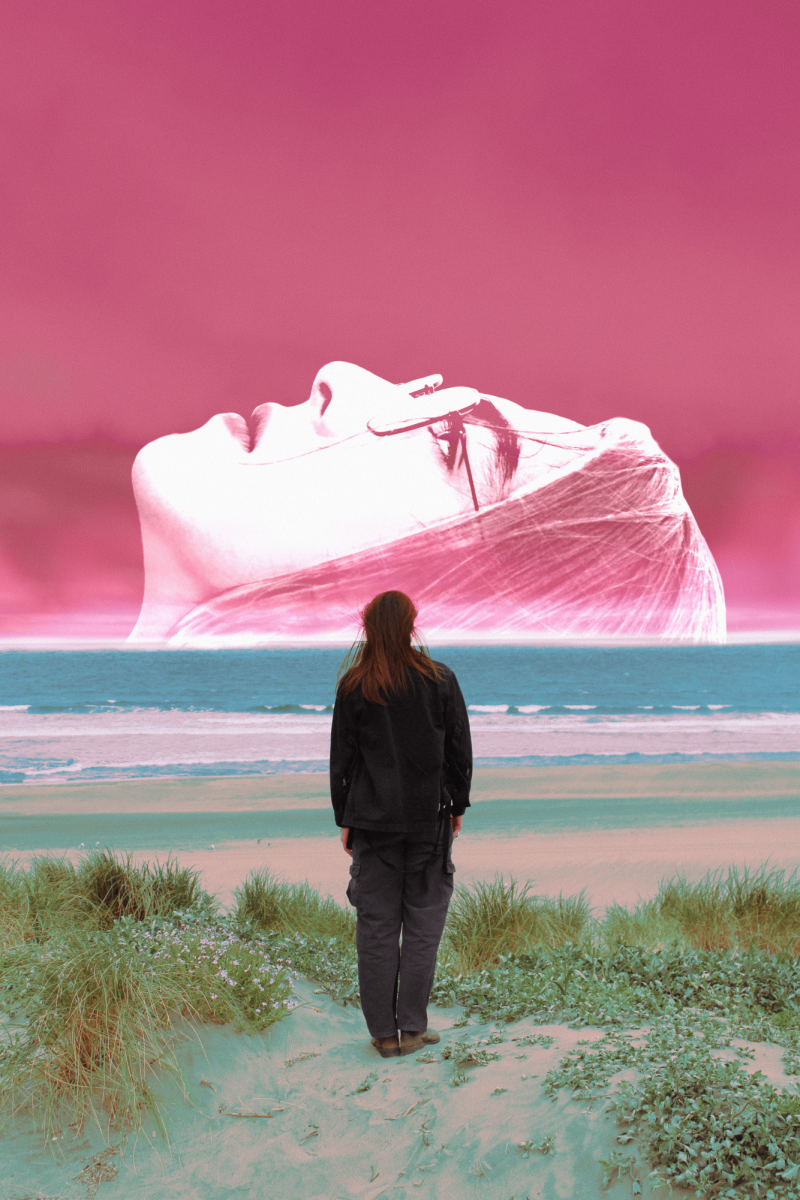

Does the truth matter when we live through our own perceptions? In Ottessa Moshfegh’s psychological thriller novel, Death In Her Hands, Moshfegh effectively compels readers to confront their flawed views of reality through Vesta, an elderly widow who lives in the woods. When Vesta discovers an anonymous note informing her that a girl was murdered, she attempts to solve this murder mystery alone, using the internet and a list of suspects. As she becomes entangled in this project, her reality becomes distorted, leaving readers doubtful of her narration’s accuracy. Through Vesta’s unreliable storytelling, the line between truth and fiction is blurred. By providing an alarmingly authentic portrayal of Vesta’s spiral into delusion, Moshfegh asks readers to reflect on their own distorted perspectives.

More than a murder mystery, Death In Her Hands is a reflection on the consequences of isolation. As the novel progresses, Vesta spirals into an elaborate fantasy where she makes up parts of the story, including events and people, and accepts them as truth. These fictional creations become part of her reality, enabling her to believe that she’s actually solving the mystery. In this way, her delusional perspective is revealed. Vesta’s delusions are largely a result of her loneliness. Removed from society, she is left with only her own mind for company. This isolation fosters her skewed perception and causes her to create narratives to protect herself from her lonely reality.

Vesta is a microcosm of the human tendency to cope with challenges by escaping into fantasy. When her dog runs away, she convinces herself the dog was kidnapped by an evil creature she calls “Ghod.” When her dog returns, rabid and aggressive, she believes that Ghod caused this. In this way, she avoids responsibility for the struggles in her life and blames an imaginary villain instead. Vesta’s escapist tendencies are shared, to an extent, by many people. Some use daydreaming as a way to cope with unwanted emotions like loneliness and boredom. For others, this escapism manifests more severely, in the form of delusions like the ones Vesta experiences. Through this, Moshfegh holds a mirror to the reader’s own distorted view of reality. Vesta’s made-up world allows readers to contemplate, How much of my experience is fabricated by my brain?