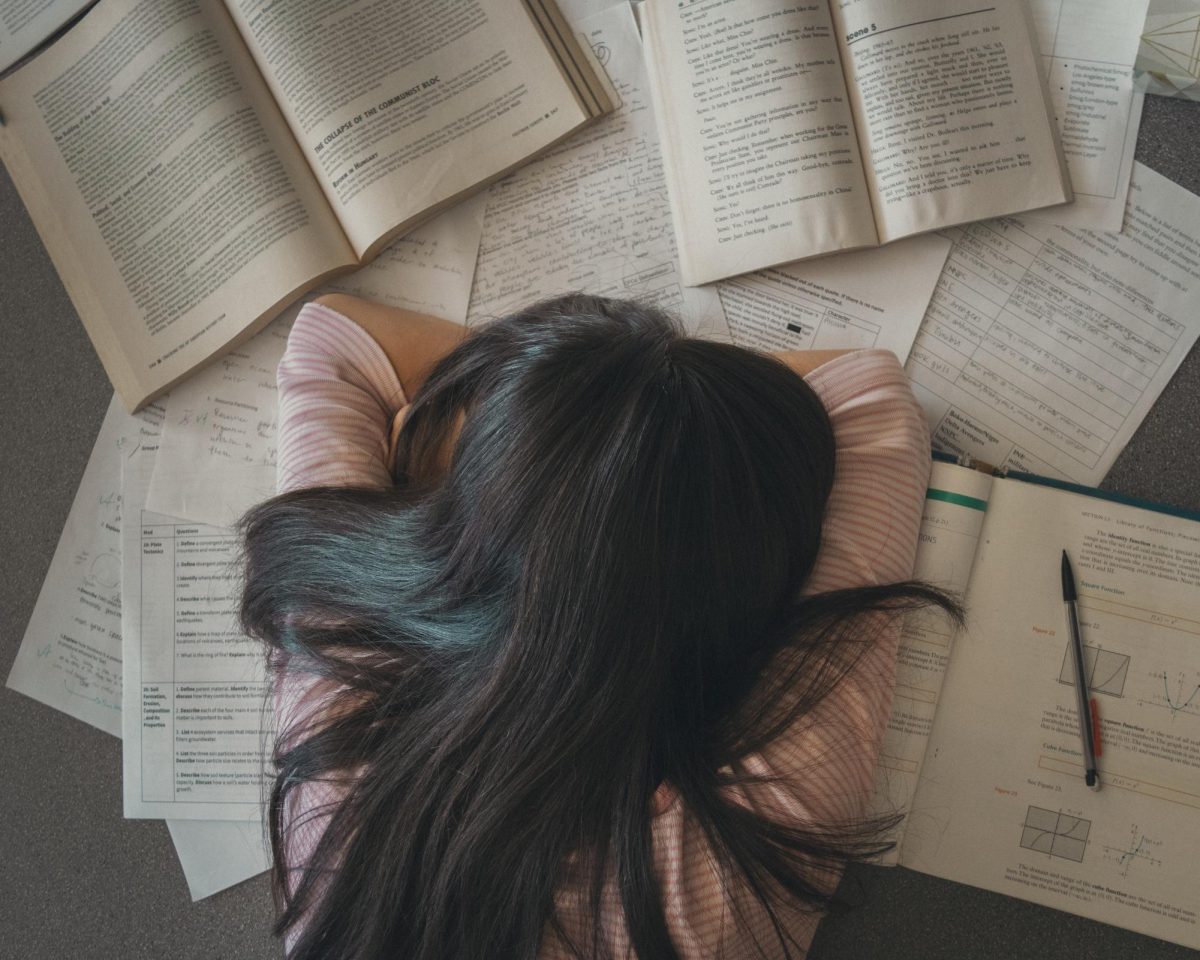

As the exhaustion of the day sets in, sophomore Violette Walenne collapses onto her bed. The clock is already ticking 6 p.m., but every time she attempts to tackle the mountain of assignments due the next day, she can’t seem to focus past the first few words. Although she knows that she shouldn’t, Walenne instinctively reaches for her phone. She knows as soon as she opens a social media app, she’ll be distracted for hours. Yet, with one decisive click, Instagram Reels fills her phone screen and a flurry of bright colors and eye-catching videos illuminates her field of vision, taking hold of her mind more easily than her assignments ever could. With her untouched schoolwork by her side, Walenne spends the next two hours scrolling mindlessly through video after video.

Walenne is among many Lowell students whose attention spans have been negatively affected by their increased consumption of social media content.

The rapid rise of short-form content has been detrimental to Lowell students. Because of the addictive dopamine feedback loop that social media provides, students are finding it difficult to focus on their life outside of social media, including keeping up with schoolwork, and even their own hobbies. This has led many students to scroll on their mobile devices mindlessly, instead of participating in the activities they once cared about. As a result, social media addiction among students has skyrocketed, as attention spans have plummeted. While many students like Walenne hope to distance themselves from social media and its harmful effects, they believe it is nearly impossible to end their dependance on such applications.

The impact of social media on human dopamine levels is causing widespread social media addiction. According to a 2021 study from the Bulletin of Integrated Psychiatry, widespread usage is making social media addiction more prevalent than ever. Social media addiction, defined as excessive or compulsive use of social media platforms, activates the brain’s production of dopamine, a neurotransmitter

that allows for feelings of pleasure, satisfaction, and motivation. In The Chaos Machine, New York Times reporter Max Fisher writes, “Dopamine creates a positive association with whatever behaviors prompted its release, training you to repeat them…. When that dopamine reward system gets hijacked, it can compel you to repeat self-destructive behaviors.” Acknowledging how human addiction to particular social media content forms, many software producers take advantage of such behaviors to increase their dopamine levels.

Producers of social media apps have successfully utilized shorter length content and algorithms to reel consumers in. Short-form video content is fueling problematic social media use, as stated by a 2021 study published by the National Library of Medicine. These media platforms, such as Instagram Reels, TikTok, or Youtube Shorts, feed users content based on an analysis of their preferences, continuously providing them with personalized videos. This constant consumption of quick and easily digestible content increases the risk of developing a dependence on social media, as stated in the study. Students like junior Ronin Datangel are experiencing this compulsion firsthand. “Short, 15-second videos [are] just so easy to watch and laugh at and then find another one to do that same thing with,” Datangel said. “It gets really addicting, even just after one scroll.”

For junior Isaac Phan, the accessibility of short-form content makes it difficult to avoid. “You could be scrolling through pictures on Instagram, and all of the sudden you come across Reels and you just need to keep watching,” Phan said. Walenne says that although she rarely enjoys using social media anymore, she continues to use it because of how convenient it is to access when she wants to fill time. Walenne describes her interactions with short-form content as “brainrot” habits. “[Brainrot] is stuff that you watch and you watch and you watch and nothing about it is particularly entertaining but it’s just so addictive. It’s like rotting your brain, it’s stupid and you know that it’s stupid but you still watch it.”

It’s stupid and you know that it’s stupid but you still watch it.

Short-form social media content has plummeted the attention spans of their consumers. As found in a study conducted between 2016 and 2021 by Dr. Gloria Mark, author of Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity, the average person can only pay attention to one screen for 47 seconds. This is a 103-second decline from 2004. Phan believes consuming short-form content has propelled this decline. “[Social media] has decreased my attention span so if a video isn’t less than a minute, I’ve got to skip it,” Phan said. “It’s too long. I don’t think I can focus on that.” Therefore, Phan finds it easier to divert his attention to easily digestible, short-form social media content.

Datangel feels his dependence on social media has harmed his work ethic and the caliber of his academics. “I can’t seem to not pick up my phone when I’m studying, even when I’m in school. I’d rather just be scrolling than focusing on my [schoolwork] and stuff,” Datangel said. “It’s affecting my grades, definitely.” However, Datangel is not alone in this. In an anonymous survey administered to 173 students by The Lowell on Sep. 22, nearly half of survey respondents reported a decline in school-related attention span over time as a result of their social media consumption.

Lowell students are also facing the effects of social media beyond the classroom, feeling as though the time they spend on social media is detracting from their hobbies. Ever since senior Leo Needleman began spending more time on sites like Youtube, he notes spending much less time engaging in his favorite activities, such as creative writing and model rocketry, despite him finding those activities more enjoyable. “Instead of focusing down a big chunk of time on something, I focus a small amount of time and then I’ll go to a social media site to watch a video or read a post,” he said. Similarly, Walenne noticed that she no longer has the attention span to do the things that she loves. “I used to be a really avid reader, I read like 20 books in one summer. Now I can’t even get 10 pages into a book without getting bored, and same thing with movies and TV shows,” Walenne said. “I just lose attention so quickly that I’ll stop watching them all together.”

Professor Mark defines these addictive tendencies as a lack of meta-awareness. “Meta-awareness means knowing what you are experiencing as it is unfolding, like when you are conscious of your choice to switch screens from work to read the New York Times,” she said. Without a good sense of meta-awareness, it’s hard to realize just how much time is passing while you scroll. This can cause users to fall into the “sunk cost attention trap,” which Mark describes as a state where it’s psychologically difficult to pull yourself out of the cycle of videos you’re in.

Datangel, who has admittedly fallen into this “sunk cost attention trap,” realized the severity of his depleting attention span when others began to confront him about it. Datangel, who enjoys playing video games in his spare time, says that his friends started calling him out for his inability to stop scrolling through Instagram Reels during their gaming sessions. “When my friends started noticing, it made me feel more insecure about how bad my attention span was,” Datangel said. “I went to a therapist to see if there was anything I could do to fix it. Nothing really worked, and I’m still afraid of the long term effects.”

When my friends started noticing, it made me feel more insecure about how bad my attention span was.

Educators, including computer science teacher Samantha Yu, believe student’s increased technology usage during distance learning exacerbated their declining attention spans. Since the pandemic, Yu and other teachers have noticed a substantial shift in the way students engage with the material being taught. “Even though the curriculum probably hasn’t changed that much, [student’s] ability to tune in, redirect focus, and lock into what they’re doing has been very obviously weakened from pre-pandemic times,” Yu said. In some cases she needs to repeat lessons because some students were not able to focus the way they could years prior.

Although Lowell students acknowledge the negative effects of social media, many find it difficult to distance themselves from these platforms. Walenne, who spends between two and 10 hours on social media every day, wishes she could use the time spent on her phone more effectively. “I feel like I could be doing so much more during the time I am scrolling on social media. Five hours, it’s so much…. I could read an entire book during that time,” she said. Yet for Walenne, among other students, the instant gratification she garners from these apps inhibits her capacity to delete them. “I keep scrolling but I hate it. I wish I could be more productive, but it’s so hard to stop,” an anonymous survey respondent said. “Sometimes it feels physically painful to stop.”

After realizing the power social media had over her, Walenne made an attempt to delete all the apps she frequented most. Anticipating its difficulty, she decided to start small. “I’m gonna try [for] like a week,” Walenne said, before announcing on her story that she was deleting Instagram “for real this time.” However, she returned to the app in just four days. In the days following, she began deleting Instagram multiple times a day, but could never go more than a few hours without reinstalling it. “I think I’ve deleted it, like, five times today,” she said. She cites the need for stimulation as a major cause for this. Although she was more productive without Instagram, she was so used to Instagram’s constant gratification loop that she felt dependent on it to feel “fine.”

Sometimes it feels physically painful to stop.

Some students, like Walenne, worry about losing the connections social media apps afford. However, since there is currently no way to disable short-form content from apps like Instagram, Walenne is unable to avoid this content while still using the more communicative features. Similarly, Phan worries that young people might feel forced to stay active on social media, despite the negative effects. “Without [social media], you fall out of touch with the rest of society,” he said. Datangel agrees, saying that virality of social media’s content forces him to continue using the apps if he wants to stay connected. “I feel that if I’m not up to date with what’s funny, and my friends make a reference to it, then I’ll feel out of touch,” Datangel said.

Concerns are being raised by both Lowell students and teachers about the long-term effects that social media can have on young people. Despite having a similar increase in social media usage over the pandemic, Yu believes that she can distance herself from these platforms in a way that members of younger generations cannot. “I’m able to break away from social media because I didn’t grow up with it,” Yu said. “As an adult, it’s easier to [quit] cold turkey than if you used social media in elementary and middle school.” Similarly, Datangel is worried by the six-year-old children he frequently sees watching nothing but short-form content in public. Since his life and attention span have already been so severely impacted by social media, he fears the impact it could have on a generation who’s grown up with it.

Experts are beginning to find ways for people to address this addiction, and its subsequent impact on attention span. In order to adapt to the impact of social media, people must learn how to take agency over their attention spans, according to Mark. “If you know you are a person with a trait of high impulsivity and you respond automatically to the sight of your phone

then make a personalized routine to create friction to make it harder to be distracted by your phone,” she said. Mark recommends setting “hooks” to pull yourself out of social media. “For example, plan a social media break ten minutes before a scheduled phone call. The appointment becomes the hook, and you know you will have to stop browsing social media and take that call.” Mark knows that it’s nearly impossible to detach from social media entirely, but she believes that learning how to take agency over your social media usage will help you break free of its effects.

Students and educators are also hopeful that the issue can be resolved. “The good news is that I think that people’s attention spans can be re-trained,” Yu said. “As long as they’re in school, and are asked to do challenging material that requires more focus… they could easily rebuild that skill.” Mark backs this up in her book. “We can become aware of our conditioning and circumstances,” she said, “and while we may not be able to control our desires, we can control our behaviors.” Datangel believes that it’s up to the users of social media to make a change. “I feel like it’s so normal for people to be on their phones all the time, and I’ve even seen people [showing off] how many hours a day they spend on their phone,” Datangel said. “I don’t think it’s really something that companies want to fix. But, I think as their audience, we need to control our time better.”

Other people feel that media companies need to be held accountable for causing these social media addictions. Multiple school districts around the country are forming lawsuits against social media giants like Meta and Bytedance, parent companies of Instagram and TikTok. For instance, the District of Maryland alleges that Bytedance, the creator of TikTok, “markets and designs its TikTok to addict young users.” The District claims that TikTok profits off targeting young people and engages them in a way where it’s hard for them to discontinue use of the app, and should be held accountable as such. In addition, several Seattle public schools have filed a lawsuit against the companies behind TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and YouTube in a federal district court, “alleging that students are being recommended harmful content online, exacerbating a mental health crisis, and social media companies are allowing it to happen.”

In an ideal world, I wouldn’t have social media. I would optimize that time to do what I actually want to.

As student addictions to social media continually rise, attention spans subsequently drop, making it increasingly difficult for students to address their own habits. Students like Walenne and Datangel know that they need to change their behaviors, but the deeper they sink into their addictions, the more distant a solution seems. Walenne desperately wishes that she was capable of spending her time doing the things she loves instead of scrolling through videos she doesn’t care about. Yet, she can’t help re-downloading the apps she uses every time she tries to quit. “In an ideal world, I wouldn’t have social media,” Walenne said. “I would optimize that time to do what I actually want to.”