Who Gets In? Opening up the Lowell Admissions Controversy

“It’s been an issue for many years about African American and Latino attendance at Lowell,” San Francisco Board of Education vice president Mark Sanchez said at an October 9, 2018 school board meeting. “[But] there’s a bigger issue that we don’t tend to talk a lot about which is whether [the San Francisco Unified School District] is following the law in actually how we enter kids into Lowell. That’s the discussion that we really should be having with the public and with ourselves.”

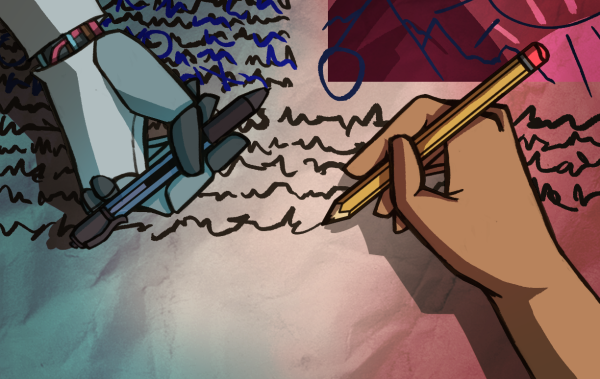

This comment, as well as others made by school board members and featured in local newspapers, such as the San Francisco Chronicle, has put Lowell’s admissions policy under fire once again, with the controversial topic pitting district officials against Lowell students and alumni. The question of the legality of Lowell’s admissions process is centered around a section of the California education code which states that the acceptance policy for a comprehensive high school, such as Lowell, must ensure “that selection of pupils to enroll in the school is made through a random, unbiased process that prohibits an evaluation of whether a pupil should be enrolled based upon his or her academic or athletic performance.”

With the matter currently under review by attorneys for SFUSD, the Board stoked the flames of the smoldering situation when its members voted unanimously on October 9 to make an amendment to Lowell’s admissions policy. This revision is paving the way for students from one significantly under-enrolled and academically struggling middle school to gain admittance to Lowell in the hope that the policy shift might help to attract more applicants to this middle school.

The admissions policy for Lowell has been the subject of controversy ever since it was put into place in 1966. In the early to mid-1960s, the number of applicants to Lowell began to exceed the capacity that the school’s physical structure could accommodate. To avoid over-enrollment, SFUSD instituted a GPA-based admissions policy. Since that time, variations of Lowell’s admissions policy have been debated within the SFUSD community and also challenged in court.

The legal saga began in 1978 when the San Francisco branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (SFNAACP), along with a group of African American parents in San Francisco, filed a lawsuit against SFUSD, then-superintendent Robert Alioto, the San Francisco and California boards of education, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction and the State Department of Education. The SFNAACP charged the defendants with participating in racially discriminatory practices and maintaining a segregated school system in San Francisco.

A 1983 consent decree settlement of the lawsuit provided that no racial or ethnic group could exceed 45 percent of the student body at any traditional school or 40 percent at any “alternative” school in San Francisco. As a result, in 1985, SFUSD implemented a race-based admissions policy at Lowell with the goal of creating a more equal distribution of ethnicities, as the school’s student body was largely Asian-American. Lowell was classified as an “alternative” school under this decree, and thus had to cap the number of students of any ethnicity or race at 40 percent. Given the significant number of Asian-American students attending Lowell at the time, these applicants would have to score significantly higher on the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills and have a higher GPA than students of other races to gain acceptance to Lowell under this new admissions policy.

By the 1990s, the 40 percent quota was becoming increasingly difficult for district officials to enforce at Lowell, given the dramatic rise in the number of Asian-American students then living in San Francisco who also qualified for admission to Lowell. Consequently, in 1993, the cutoff test score for admittance to Lowell for Asian-American students jumped to an all-time high, while scores for Caucasian, Latinx and African American students remained the same, resulting in dozens of Asian-American students being rejected from Lowell despite having scores well above those students in other racial groups.

In a 1994 lawsuit, Ho v. San Francisco Unified School District, the Asian American Legal Foundation and a group of parents from the Chinese American Democratic Club challenged the use of racial quotas to limit the enrollment of Asian-American students in San Francisco public schools. As an outcome of the suit, SFUSD agreed to create a new “diversity index” system for admission to all public schools. The “diversity index” would consider a variety of other factors, including socioeconomic background, mother’s educational level, academic achievement, language spoken at home and English learner status, rather than a student’s race. For Lowell, then-superintendent Bill Rojas proposed a new admissions policy, which entailed the establishment of a single academic entrance criterion for students of all ethnicities and races. However, in order to comply with a federal desegregation plan, about 20 percent of applicants to Lowell would come from families on public assistance and/or residing in public housing. This pool would be judged partly on their academic record, but also on involvement in clubs, sports, hobbies and community work. Rojas’ proposal was approved unanimously by the Board of Education in February 1996 and went into effect for the 1996-97 academic year. Under the new policy, all students would now be required to score 63 out of a possible 69 points to be admitted to Lowell, except for students residing in public housing or on public assistance, who would be required to score above 50 points to be admitted to Lowell.

Five years later, in 2001, Lowell’s current “three-band” admissions policy was put into place by the SFUSD Taskforce on Admissions to Lowell High School and School of the Arts. According to a historical summary about the policy from SFUSD, “The Taskforce believed that [the band system]… will ensure that SFUSD identifies students who have demonstrated a pattern of achievement and who will benefit from the unique and challenging program at Lowell, while providing welcoming, equal access to all students with the potential for success at Lowell.”

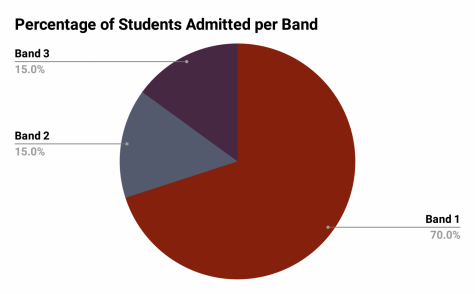

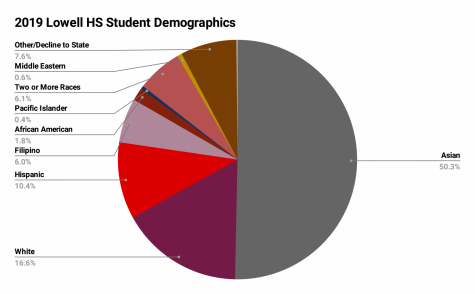

Data courtesy of Lowell High School

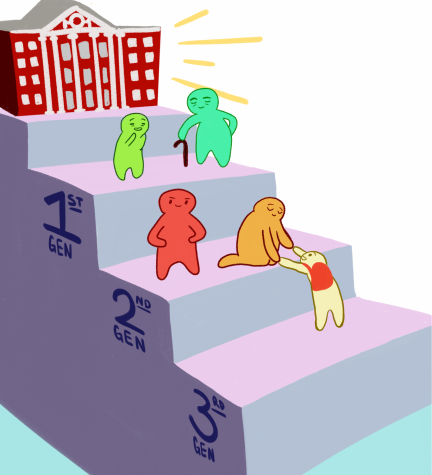

Through the current band system, applicants to Lowell can be accepted through one of three bands: Band One, through which 70 percent of incoming freshmen are admitted; Band Two, through which an additional 15 percent of incoming freshmen are admitted; or Band Three, through which the final 15 percent of incoming freshmen are admitted.

Band One admission is based solely on a student’s GPA in the seventh grade and the first semester of eighth grade, along with the score earned on the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) for students applying from public schools, or the Lowell Admissions Test for students applying from private schools.

Students admitted through Band Two will also have been admitted based on their GPA and SBAC results or Lowell Admissions Test scores. However, with lower GPAs and test scores than students qualifying through Band One, these Band Two students are admitted with consideration to a third criterion that includes elements such as community service, socioeconomic status and ability to overcome hardship.

Students gaining admission through Band Three must come from San Francisco public or private schools currently underrepresented among the student body at Lowell.

On October 9, 2018, the Board of Education revised the Band Three policy to stipulate that, unlike other Band Three schools that have a cap on the number of students who can be admitted to Lowell, all students from Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School who qualify under Band Three will

be accepted to Lowell regardless of their overrepresentation or underrepresentation at the high school.

Data courtesy of Lowell High School.

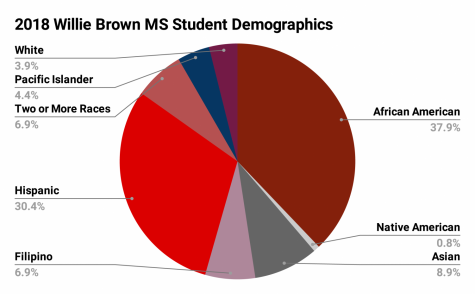

Sanchez says the key goal of the policy amendment is to increase both enrollment and racial diversity at Willie Brown, a middle school in which 76 percent of the student body is socioeconomically disadvantaged, and the majority of students are African American (35.9 percent) and Hispanic (28.8 percent). He says that guaranteed acceptance to Lowell through Band Three for qualifying Willie Brown students may provide an incentive for more SFUSD families to send their children to the middle school. “One thing it could do is it could make Willie Brown a more integrated school and a more robust school,” said Sanchez. “It’s a school that can hold 600 to 800 kids and it has fewer than

Data from the California Department of Education.

300 [382 per the most recent statistics from the California Department of Education]… So, I think that having this policy for Willie Brown will be really helpful over time to make it more diverse.” In February, Sanchez was already beginning to see such potential positive effects, with 100 students applying to Willie Brown for the 2019-20 academic year as opposed to the typical 60 students of previous years.

However, in the eyes of many Lowell students, including senior Chris Ying, this latest adjustment to their school’s admissions policy amounts to one more step toward dismantling the Lowell meritocracy. “There’s nothing wrong with awarding people for the work that they do and the work they put in,” Ying said. “If the numbers suggest that you have been putting in work and you have been putting in the effort that other people don’t put in, then I think that you should be rewarded with that and you should be able to go to a higher school where you can learn even more and be able to experience education on a different level with people who are just as passionate as you are about learning.”

The fear of Ying and other students that Lowell could become a watered down academic high school originates from what they know about the academic reputation of Willie Brown, which is currently ranked in the bottom 5 percent of California public schools. “You have to take a look at whether or not this could be used as a slippery slope, in the sense that you admit a couple [Willie Brown students] based off this and then we expand it into other schools that are not performing that high,” Ying said. “We target the schools because they are minority heavy and then you have to start asking yourself, okay, Willie Brown was just a drop in the bucket, but if we’re just continuously pouring water into the bucket, then maybe we’ll see some of the negative effects.”

From the Board’s standpoint, Sanchez is confident that such concerns will not come to pass. “It’s such a small percentage of 10 or 11 kids so [the policy] will have an impact on Willie Brown in a positive way and it’ll be negligible on Lowell’s side,” he said.

Numbers aside, many Lowell students, including sophomore co-president of the Black Student Union Shavonne Hines-Foster, are concerned that the Board is not making a thoughtful effort to ensure that the students from Willie Brown and other low-performing middle schools succeed once they are enrolled at Lowell. “I feel like now everyone is just targeting Lowell because of the low diversity rate,” Hines-Foster said. “So, I feel like [the Board] is just throwing something on the plate that we can eat for now and we’ll deal with the rest of it later.”

To help those students who are from schools and racial groups that are currently underrepresented at Lowell, Lowell Alumni Association (LAA) president John Trasviña says the LAA has proposed to SFUSD implementing a program in which tutoring and necessary academic preparation would be given to students wishing to apply to Lowell. This “mentoring program” would be offered to students starting in the fifth and sixth grades, so that by eighth grade, they would have grades and test scores that would give them a higher chance of gaining admission to Lowell. “We would work with [the district] so that the schools could identify students of promise who come from backgrounds that are not well represented here at Lowell,” Trasviña said. “[We would] start with them three years in advance to give them the kind of mentoring, tutoring and preparation so that they would get a greater familiarity with Lowell High School, with Lowell students, with Lowell programs, whether it’s the play, or whether it’s sports, or whether it’s with different organizations so that students would feel that this is what it takes to get into Lowell.”

Ultimately, Trasviña believes that such a program should begin even earlier than fifth grade. “What needs to be done is to increase the academic offerings for all students at all schools, starting at grade one if not earlier,” he said. “Developing that pipeline would enable students to have the necessary preparation and grade level attainment that would then make them qualify for Lowell and make them be competitive for the admissions process.”

So, I feel like [the Board] is just throwing something on the plate that we can eat for now and we’ll deal with the rest of it later.

— Shavonne Hines-Foster

Freshman Kuresa Liu, a graduate of Willie Brown, says that coming to Lowell has indeed been a big adjustment academically and socially. “At Willie Brown, a lot of times the teachers would go through their lessons, but they would kind of give up on those who didn’t want to listen,” he said. “There would be a lot of goofing off in the class while the teacher was teaching and it was a little bit of a struggle trying to learn. I was kind of one of those people who goofed off, so academically, coming here was a lot different because it’s a lot more serious.”

Liu, who is Polynesian, was “kind of worried I wouldn’t find many people like me,” he said. “I was worried about sticking out.” He also was fearful about telling his classmates that he had attended Willie Brown. “I’m aware that Willie Brown isn’t the greatest of schools, like there are a lot of fights,” he said. “In my head, I thought that if I told people that I came from that school, they would think differently of me, that I’m like those types of people who are aggressive and mean.”

Now, more than halfway through his first year at Lowell, Liu, who has forged friendships through the Lowell Polynesian Club and his classes, feels comfortable at the school.

Landon Dickey, a member of Lowell’s class of 2005 and now a special assistant to the superintendent for African American achievement and leadership, says that African American and Latinx students are often reluctant to apply to Lowell due to the small number of students of their race currently attending Lowell. However, he believes that the revised Band Three policy will bring more African American and Latinx students into Lowell, helping to gradually erase the stigma surrounding the high school. “There are a lot of students that feel like Lowell is not for them based on who they see going to the school,” Dickey said. “I think that just seeing an increase in the numbers of underrepresented students that are able to attend Lowell will start to change the narrative around Lowell.”

In an attempt to help ensure the success of the seven Willie Brown graduates joining the Lowell student body next fall, the Lowell administration will introduce to them, and other underrepresented students, three programs principal Andrew Ishibashi has established to help provide academic and social support to African American, Latinx, Filipino and Pacific Islander students.

Since he joined Lowell in 2007, Ishibashi has been actively recruiting African American, Latinx, Filipino and Pacific Islander students. Every academic year, before applications to Lowell become available, Ishibashi reviews a list of every Latinx, African American, Filipino and Pacific Islander student in SFUSD who has at least a 3.0 GPA. He then sends letters to the families of those students, encouraging them to meet with him and have their student apply to Lowell. Ishibashi also assists African American, Latinx, Filipino and Pacific Islander families with their applications to Lowell.

His efforts have paid off to some degree, with the number of Latinx students attending Lowell doubling since he became principal. However, the African American, Filipino and Pacific Islander student population at Lowell has remained relatively unchanged.

Board of Education vice president Sanchez recognizes that SFUSD has much work to be done concerning Lowell, its admissions policy and the perceptions around racial disparity. He also acknowledges that the responsibility for the situation as it stands today lies with San Francisco’s policymakers. “It’s not the students’ fault, it’s not the teachers’ fault, it’s not Lowell’s fault, it’s not the [Lowell] Alumni Association’s fault,” he said. “It’s our fault as the policymakers, as the people who are charged by the public to ensure that our district is equitable and fair-minded and leading us in a positive direction for all of our students.”

Although the debate has settled down for now, given the history surrounding Lowell’s admissions policy, it’s just a matter of time before the issue resurfaces. Finding a balance between academic rigor and racial diversity is a goal SFUSD and much of the Lowell community wants to achieve, but how to achieve that goal remains elusive.