Shoplifters will not be prosecuted

A sophomore sits down at their usual table in the courtyard to enjoy their free block. A friend brings beef jerky and gum to share, casually throwing them on the table for the group to enjoy. No one bats an eye at the fact that he has just stolen these snacks from the nearby Lucky’s. Knowing a friend who does this regularly is not something unique to this lunch table.

During their free blocks, many students head to either Stonestown or Lakeshore Plaza to shoplift. When caught, most suffer little to no consequences, and, knowing that they will not face repercussions, keep doing it. Even if their fellow students find out, almost none are ever reported, and the administration doesn’t know that there is an issue.

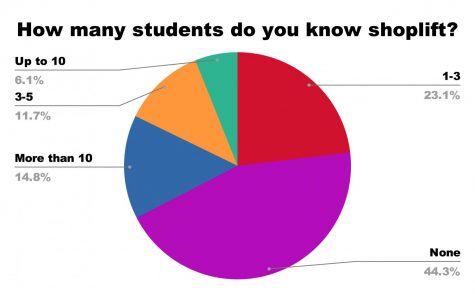

Data from a random survey of 300 students

(3 registries per grade) conducted by the Lowell in March 2019

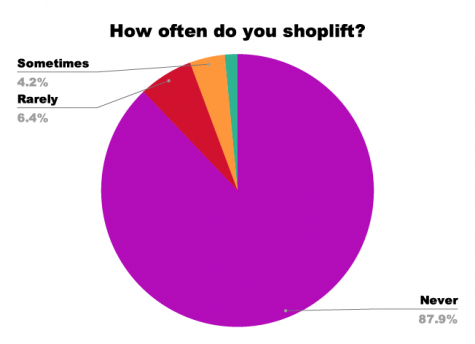

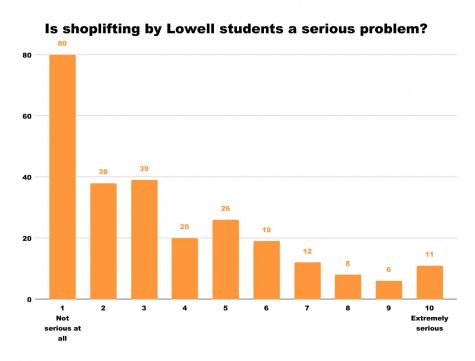

Lowellites’ majority opinions about shoplifting are apathetic. According to an anonymous survey taken by randomly chosen registries, only 11.5 percent said that they themselves shoplifted, but 54.4 percent said that they knew of someone at Lowell who did shoplift. Fifteen point one percent said that they knew of more than ten people who shoplifted. Eighty three percent of those said that few of those they knew had ever been caught. The number of those who were punished almost exactly matches the number that were caught. Ninety nine point three percent of responders never reported shoplifters to adults. Of the most common responses as to why surveyees never reported them, many included the word “snitch,” some variation of “not my business” and “[the shoplifters] are my friends.” Less common responses said that they didn’t report because so many people did it, because of loyalty and because they didn’t think it was an issue or not harming anyone.

Data from a random survey of 300 students

(3 registries per grade) conducted by the Lowell in March 2019

Most Lowell students steal things they desire, not what they need. Stealing anything from their most common target, snacks, to clothes, to high-risk things like Apple Airpods and hard liquor, they take items that would not reasonably be justified as necessary and unaffordable, or otherwise difficult to obtain. Even though some of their targets have been higher-end and more dangerous to be caught with, and their classmates have been aware of their antics for some time, they continue to do it–both during and after school hours.

One student, Tom, a Lowell student who we have given a fake name because he prefers to remain anonymous, has been shoplifting on a regular basis since last year. He claims that he has probably stolen over $3,000 worth of items from Stonestown over just two years, and well over $1,000 in snacks from Target alone. He began stealing when one day, he simply felt hungry but wasn’t carrying any money with him, and took some food and left without paying for it. His minor “snatch-and-runs” quickly turned into a small scheme, and he developed a tried-and-tested method of getting things out of Target. He also occasionally resold items stolen from other stores, even managing to resell a total of six sets of Apple Airpod wireless headphones, which Apple sells for $159. However, after the store he took from significantly increased their security and he realized what would happen if he were caught with $159 worth of merchandise, he stopped stealing from Apple.

Tom doesn’t see shoplifting as an issue, and even provides encouragement to prospective shoplifters. “If you’re confident that you [won’t] get caught, you should probably start doing it, ’cause it saves money,” Tom said. “If you do get caught, that’s kinda tough, but… just don’t steal like, AirPods. Then if you get caught, you’re f****d.” Every day and every off block I’ve had at Lowell, I’ve known that there is always a lot of kids going down to Target or Lucky’s to shoplift — Jack Stern

One reason for the persistence of stealing is that a majority of youth shoplifters don’t plan to shoplift in advance of committing the crime, only doing so once they are already in a store, according to Patricia Raffini, executive director of Colorado Springs Teen Court. “Most adolescents can’t explain themselves,” said Raffini. “In rare cases, genuine need is the issue. Some are troubled and looking for attention, or lashing out at authority. And many do it to fit in with peers.”

To shoplifters, stealing is an isolated crime, strictly between them and the store. However, simply by interacting with them, shoplifting adolescents can influence their peers to shoplift as well, according to a 2016 study conducted in the Netherlands. The study concluded that those who frequently interacted with their peers who committed crimes were themselves more likely to commit crimes, which means that as more and more students shoplift, more are motivated by their friends to follow suit. To put some numbers into perspective, according to the National Association of Shoplifting Prevention (NASP), 89 percent of American youth know of other youth that shoplift, and 66 percent say that they regularly interact with them. Additionally, a 2011 study from the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law showed that shoplifting is connected to other problems, like poor grades, behavioral issues and substance abuse.

Many Lowell students are aware of their peers stealing. “Every day and every off block I’ve had at Lowell, I’ve known that there is always a lot of kids going down to Target or Lucky’s to shoplift,” sophomore Jack Stern said. Despite this, neither he nor anyone he knows has not reported the stealing to anyone. “No one really cares bruh, unless you’re like a snitch,” Tom said.

There haven’t been any cases of students reporting Lowell shoplifters, according to Beauvais. From the survey’s many responses that contained the word ‘snitch’ in them, it’s quite clear that student don’t want to betray their peers. “I know that there’s kind of a culture of ‘snitches get stitches’ and that kind of stuff,” Fong said. “Those who do report do remain anonymous, and we try and make sure that if you guys see something happening then we want to make sure that we know about it just to make sure that you guys are safer.”

Data from a random survey of 300 students

(3 registries per grade) conducted by the Lowell in March 2019

When asked if he worried about the consequences for his actions, Tom said, “Uh, not really, it’s like, you know those small stores? Those are like, off-limits. But like, Target, it’s like hella big, and it’s like a big-ass company, it’s fine [to shoplift from], ’cause they don’t really lose that much money.” These large companies are “too big to hurt,” according to Tom.

In reality, shoplifting can cause issues for buying customers of those stores. When stores lose money from shoplifting, they have to offset those losses somehow, by raising store prices, or they may install more security, possibly making customer service worse, wrote Neil Kokemuller, a reporter for the Houston Chronicle. Additionally, because a shoplifter isn’t going to pay taxes on the stolen items, the public also loses money for government projects, and police and courts have to deal with the frequent shoplifting cases, since there are about 27 million shoplifters in the US according to the NASP. Last year, there were $16.7 billion in losses just from shoplifting, as revealed by the 2018 National Retail Security Survey. Convenience Store News reports a total $48.9 billion from shoplifting and employee theft combined.

Another Lowell student and a friend of Tom’s, Alex, who also asked to remain anonymous, used to shoplift for reasons similar to Tom, but stopped because she felt bad for the stores, was afraid of what would go on her academic record and because she didn’t want to disappoint her parents. “I do [feel bad for the stores], and I’ve made a conscious decision to stop shoplifting,” Alex said.

Even with the significant amount of Lowell students shoplifting, there is no clear guideline on discipline or prevention, because the school appears to be largely unaware of the scope of the issue. “It’s almost a nonexistent problem,” said Dean David Beauvais. “It’s not my number one issue here. Not even close.” Counselor Cheryl Fong estimated that there were fewer than two dozen students who shoplifted at the school. While she could not comment on disciplinary policy for a student found to be stealing, Fong added that, given enough cases, “We would have to probably, as a school, look at the off-campus policies, and see if that privilege needs to be taken away.” However, the great majority of students who responded to the anonymous survey were aggressively against changing off-campus free blocks in any way.

Tom didn’t fear being caught at all, citing the experience of one of his friends who stole vodka from the nearby Lucky’s and got drunk with it at school. “The school can’t really do shit ’cause it’s not on school property,” Tom said. “Cause you know that guy that got drunk? [The school] didn’t do s**t to him, so…I barely steal stuff that isn’t snacks, but I do it a lot, so like, if I get caught for it, it’ll probably be fine.”

Every one of the students interviewed for this article said that they did not fear punishment from the school, because none of their peers were ever heavily punished. However, according to the NASP and Palmer Recovery Attorneys, even if no criminal charges can be brought against the student, stores can still make civil demands against the students, which essentially forces their parents or guardians to pay for what the students stole, even if it was eventually returned.

M. Taguinod, a security supervisor at Stonestown, estimated that every day, about eight students are caught shoplifting from a store, and out of those eight, two are normally from Lowell. Stonestown’s response to catching minors with low-value items is to give them a talking-to to try and change their minds, and forcing them to pay for what they tried to steal, according to Taguinod. Then, in order to stop it in the long run, they collect photo and video evidence and other information to present to the minor’s school. “We actually keep communication with them, and we try to work out a solution,” Taguinod said. Shoplifting is not acknowledged as an issue by students and the administration alike

Beauvais, however, says that the two-a-day number provided by Taguinod is inaccurate. “A lot of times Stonestown’s people think that they’re Lowell students [stealing] when they aren’t,” he said. “I don’t get contacted by stores a lot saying that this is a problem.”

Currently, the school doesn’t have a specific policy for dealing with student shoplifters. “It’s up to the store to involve any police,” Beauvais said. When a student is caught and it is confirmed that they are from Lowell through video evidence, they are disciplined, which usually entails a call to a parent or guardian.

Even though Stonestown security shares video evidence with the school dean, and Principal Ishibashi can request evidence from Stonestown when there is a related incident that comes to his notice, shoplifting is still taking place. Because the administration’s policy is to leave punishment up to the stores and if necessary, police, when a student is reported to the school, Lowell can do little to keep them from stealing again. Fong suggested that there could be contractual agreements for students to not leave campus if they have been caught shoplifting, which at least prevents shoplifting during school hours.

Shoplifting is not acknowledged as an issue by students and the administration alike. While many students are aware of its prevalence, they don’t see it as a problem. The administration isn’t fully aware of the magnitude of the issue, and, as a result, doesn’t see the need to create distinct policies that discourage it. Until these two sides gain a more complete picture of the issue, the amount of shoplifting by Lowell students is unlikely to decrease.