Lowell social studies teacher Erin Hanlon, who is in her first year of teaching, wanted to live in the city where she works but was unable to find affordable housing. She wasn’t looking for much. “I just need a clean and quiet place to live where I can cook,” Hanlon said. But her search for housing yielded only less-than-optimal results. In one case, a lady refused to rent to her because Hanlon is not tenured. Most of the housing options that she could afford were “flop houses,” unclean and unattractive living complexes shared by many roommates, according to Hanlon. The only housing in San Francisco she could find within her budget wasn’t much more than a room in someone’s house. “You weren’t allowed to use the kitchen,” Hanlon said. “You had your room in his house, and the bathroom, and that was it.”

The cost of housing forced Hanlon out of the city to the East Bay and now to Pacifica, where she lives with a friend’s mother. So why is it that a full-time employee at a prestigious high school can’t make enough to afford decent housing in the city where she teaches?

The combination of unusually low teacher salaries and rising housing costs in San Francisco has been creating problems for teachers throughout the district. Many struggle to pay rent, and most can’t afford to buy houses. Because of these obstacles, fewer people are entering the teaching profession in the first place, and many of those that do, switch professions after a short time.

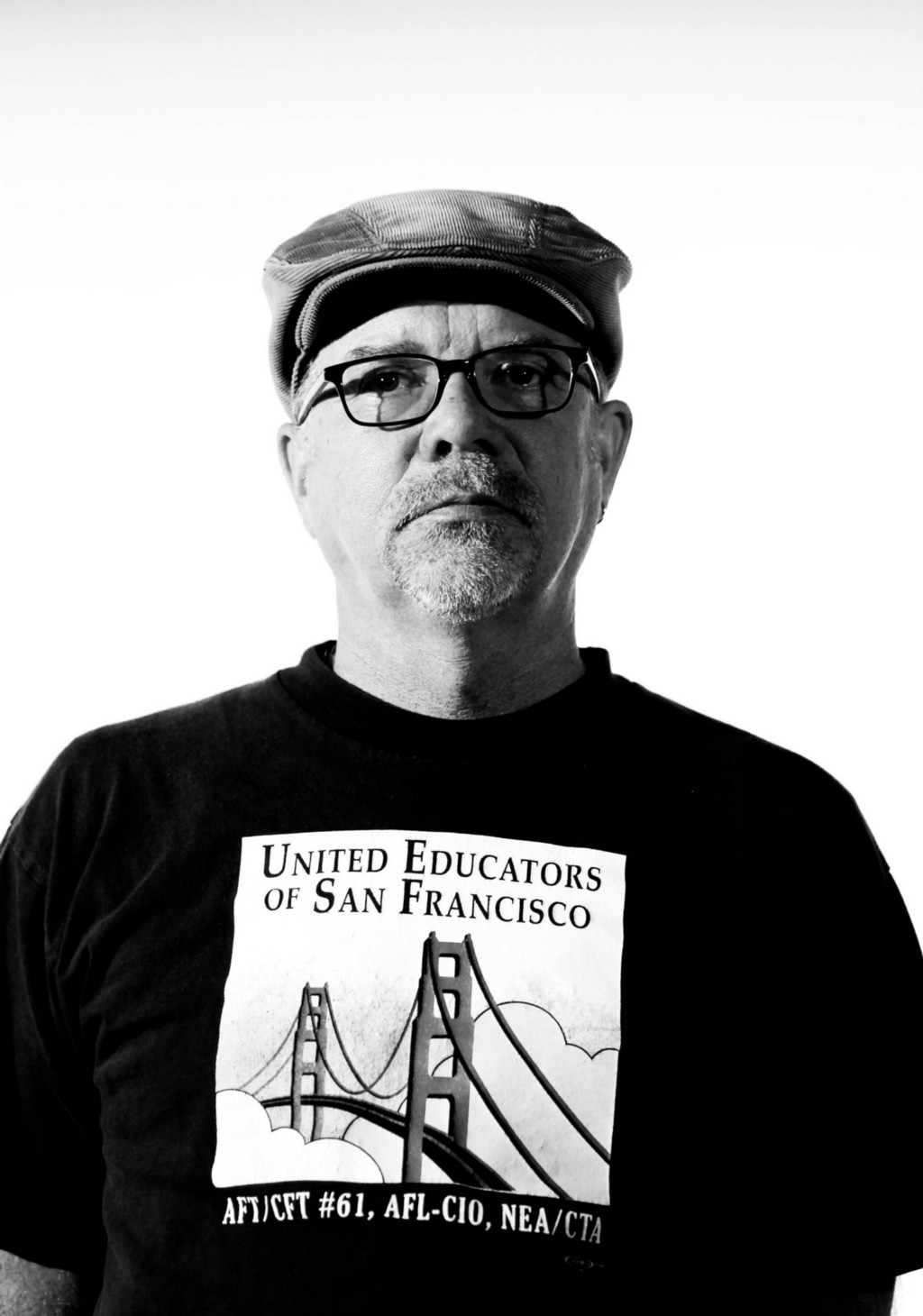

The root of many of these problems is low teacher pay. SFUSD teachers receive wildly disproportionate pay compared to teachers in the rest of the state. San Francisco is one of the most expensive housing markets in the country, and has one of the lowest average teacher salaries in California. A credentialed first-year SFUSD teacher only makes $52,687 according to the contract between San Francisco Unified School District and United Educators of San Francisco. In contrast, a credentialed first-year teacher with a Bachelor’s degree in the Santa Clara Unified School District makes $67,233, and first-year teachers there with a higher level of education can make up to $74,689.

More experienced SFUSD teachers can make more than $52,000. Unionized teachers are paid on a standardized scale, where all teachers of the same work experience and level of education are given the same raise every year. So a teacher can make up to $91,934 a year, but that’s only after 28 years of work, according to the SFUSD United Educators Union contract. That’s 28 years many people can’t afford to get through with the high cost of housing in San Francisco.

It’s also nowhere near the $107,922 that a top earner in Santa Clara Unified School District can make in less than half that time, after only 12 years of experience.

Social studies teacher Matthew Bell is in his 10th year of teaching. He’s a second-career teacher who left his higher paying job working on political campaigns because he has a passion for teaching. “Despite the significant pay cut, it was always plan A, and it was much more conducive to family life,” Bell said. “If you had asked me when I was 17 what I wanted to do, it was to be a history teacher.”

Some people don’t understand how much work goes into being a good teacher, according to Hanlon. “They think, ‘oh you work from 8–3 and you have summers off’ that’s easy,” she said. “I have never worked so hard in my life. I should be making a fortune, because I’m putting in very long days.”

So why is teacher pay so low?

SFUSD’s budget comes primarily from property taxes. In the 2016–17 fiscal year, the city brought in around $2.5 billion. Of that amount, about a third goes to educational services, including SFUSD. The district’s budget has been increasing the last few years, with the 2016–17 budget being $823.9 million, up $38 million from the year before. However, only $11 million of that went to increasing employee salary.

According to assistant principal Dacotah Swett, this is due in part to other high operating costs. A large part of the budget goes to programs that other districts don’t often have, like Wellness Centers, immersion programs and English as a Second Language programs.

Still, the allocation of district funds is a bit mysterious. SFUSD administrators have looked into where the budget goes, with no concrete results, according to a San Francisco Chronicle article. According to school board president Shamann Walton, about 50 percent of the district’s budget goes to “overhead” costs, meaning district offices and personnel. That means only 50 percent of our budget actually goes towards running schools and paying for teachers.

“At some point the walls might close in on us.”

With how little money out of the budget ends up in teacher’s pockets, many can’t afford to live in San Francisco.

According to the Numbeo Cost of Living Index, which scores the price of living in a city based on prices for rent, groceries, restaurants and local purchasing power, San Francisco has the second overall highest cost of living in the continental United States, behind New York City. The factor that makes San Francisco so expensive is the cost of housing, with average monthly rent amounting to the steep price of $3,684.

Take computer science teacher Arthur Simon for example. Simon was evicted from his home in 2002 under the Ellis Act, which gives landlords the unconditional right to evict tenants to “go out of business,” according to the San Francisco Tenants Union. Unable to find affordable housing for his family, he moved across the bay to Albany.

Bell is fortunate: he lives in the city with his family, but getting housing wasn’t easy. Before moving here, his family lived in a rental in Pacifica until the landlord decided to renovate the house and jack up the rent, forcing them to move out. Luckily, Bell found a house in the Parkside neighborhood but he had to bargain with the landlord for a lower rent. “The place had been paid off for years and years, and we negotiated them down,” he said. “Basically saying, ‘Look I’m a teacher, we have a daughter, so can you work with our family?’”

Still, it’s not cheap. “Our monthly rent takes up my entire paycheck,” Bell said. He can afford that only because his wife also works.

Though Bell wants to live and work in San Francisco long term, he doesn’t know if it’s possible. A move to a state with more affordable housing may be inevitable.“We are under no illusions that they aren’t going to raise our rent,” Bell said. “At some point the walls might close in on us.”

Bell wanted to buy in San Francisco but couldn’t afford it. Buying a house in San Francisco is an expensive proposition. A two or three bedroom house in the Lake Merced and Sunset areas costs upwards of $1 million. Average down payment on a house is between 10 and 20 percent of the total cost. For teachers who make about $50,000 a year, the down payment alone would comprise two to four years of salary. And for teachers like Hanlon, who are in the process of paying tuition or have outstanding student loans, buying a house or even paying rent is practically impossible.

When teachers can’t afford to live in the city, they’re forced out. Living outside of the city doesn’t just make for a frustrating commute. Teachers who live far outside of San Francisco can’t be a part of the school community in the same way they could if they lived closer. “For a sports event or a play or whatever, I can’t leave or come back because it’s more than half an hour each way, so I need to decide: Do I go home and do work, or do I stay and be part of the school community?” social studies teacher Amanda Klein said. “Those are decisions I wouldn’t have to make if I were 10 minutes away.”

Isolation and lack of community are big reasons teachers across the nation leave their jobs, according to a report by the National Institute on Teaching and America’s Future.

“New teachers and young teachers will go to a school district in the South Bay, or in the North Bay. They don’t even apply.”

Teacher turnover, the percentages of teachers who leave their job compared to the amount who stay, has been increasing in recent years in San Francisco and across the country, according to a study by the National Department for Education Statistics.

However, teacher turnover is only part of the problem. Because wages are higher and the cost of living is lower in surrounding school districts, fewer and fewer people are applying to work in SFUSD in the first place. “New teachers and young teachers will go to a school district in the South Bay, or in the North Bay,” Swett said. “They don’t even apply.”

Fewer people are teaching altogether. Eight percent of teachers in the United States leave the profession each year, and 17 percent of new teachers will switch careers within five years, according to a study by the Department of Education. That number is about four percent higher than other similar professions in the United States, and higher than teacher attrition in other countries similar to the United States.

Though the teacher shortage has been a problem in all of SFUSD, the impact hits harder in low-performing schools, where teachers are often less satisfied with their work conditions.

SFUSD has a list of “hard to staff” schools, which are mostly located in less affluent neighborhoods. The list has 25 schools of different levels, including Starr King Elementary, James Lick Middle School, Thurgood Marshall High, Everett Middle School, John O’Connell High School and Willie Brown Junior Middle School.

Teachers at these schools receive an extra $2,000 on top of their salaries, but often still struggle. According to an Examiner article, 40 percent of Bayview school teachers were new in the 2016–17 school year, compared to the district’s overall 21 percent.

Turnover rates are already abnormally high in low-performing schools, so teachers being unable to find adequate housing makes staffing them even harder.

Teacher housing, or lack thereof has been a hot topic in San Francisco. People aren’t staying quiet. The United Educators Union held an emergency hearing on educator housing back in March. At the meeting, hundreds of SFUSD employees gathered to share their stories of trying to live in the city, all with one thing in common — it’s too expensive.

After decades of talk about affordable housing for teachers, a San Francisco Chronicle article on a homeless SFUSD teacher prompted mayor Ed Lee to promise $44 million towards a subsidized teacher housing complex at the Francis Scott Key Annex in the Outer Sunset, a site already owned by the school district which is currently being used as a playground, skate park and office space.

According to the mayor’s office, the complex will include over 150 mixed size units for low-to-middle income SFUSD educators. The housing is set to be available in mid 2022.

“The subsidized housing idea is a band-aid on a severed limb. I need to be paid more so that I can afford to teach here in the city.”

Projects like this were made easier to do in 2016 when the school district’s Employee Housing bill was passed. The goal was to have a state-wide policy that supported the development of rental properties for district employees on land already owned by the school district.

Other school districts have done similar things. Santa Clara Unified School District’s “Casa Del Maestro,” as the district calls it, is a 70-unit housing complex on district owned land, that has been around since 2002. It provides below-market housing for teachers for up to seven years. A two-bedroom apartment costs less than half of what it would at a market price, at $1,500 a month.

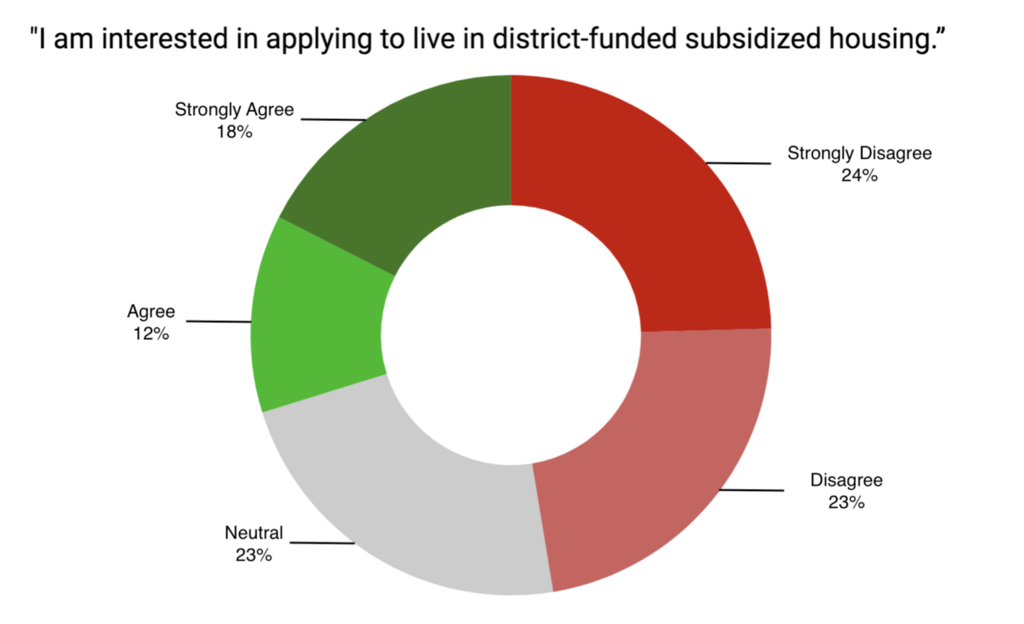

The Lowell staff conducted a survey of Lowell teachers to find out how the San Francisco housing crisis is impacting them. Some teachers don’t think the subsidised housing proposal will get to the root of the problem. “The subsidized housing idea is a band-aid on a severed limb,” said one teacher. “I need to be paid more so that I can afford to teach here in the city.”

Another teacher expressed concern that her family would not qualify for subsidizing housing because her household income is too high, even though they’re still living paycheck-to-paycheck in their rent controlled apartment.

There are other ways to address the lack of teacher housing in San Francisco. Hanlon thinks repealing Prop 13, which limited the amount of property tax homeowners pay back in 1978, would be a better solution. According to her, this would incentivize people to build more housing, and help all “essential workers” to find housing, not just teachers.

The city does have other programs aimed at helping teachers afford housing, including the “Teacher Next Door” program, which gives grants to SFUSD teachers to help them buy houses. But qualifying for the program is fairly difficult. In order to get a loan, no one in a teacher’s household can have owned a house in the past three years. In addition, the teacher must contribute at least five percent to the purchase of the house. Even then, the $40,000 loan is miniscule compared to the price of a house in San Francisco.

Even teachers who do qualify for Teacher Next Door find it hard to use. “The information is not convenient,” Hanlon said. Teachers must attend an informational session to be in the program, however these sessions can be inconvenient. “They tell us the day before, and the meeting is in some weird part of the city, it’s not easy to understand or accessible,” Hanlon said. “They tell you to bring your bills and your budget.”

Union representative Katherine Melvin is skeptical of the program. “It’s more work than it’s worth,” she said.

Not all teachers even know about the program, especially new teachers who are more likely to benefit from it, like Klein. When asked, she said she “didn’t know it existed.”

When teachers can’t afford to live in the communities they work in, the entire district suffers. Simply acknowledging the problem can’t give educators better salaries and living conditions. Though efforts have been made, there’s still leagues to go. According to Klein, the place to start is with our values. “Part of it is that people don’t value teaching the same way they value other professions, like medicine and law,” she said. “You don’t go into teaching for the money. You get teachers who want to teach, but it would be nice if we were equally compensated.”