Looking back and moving forward on racial equity at Lowell

Shavonne Hines-Foster, left, Aubrey Chikere, right

Sophomore and Black Student Union (BSU) Public Relations officer Aubrey Chikere sat in her room, playing video games after a long day of school. Immersed in her game, she barely noticed the notifications buzzing on her phone. She needed to finish the game before starting her homework so her phone would have to wait. The buzzing suddenly sped up. Figuring it must be something important, she picked up her phone and opened the BSU group chat. That’s when she saw them: screenshots of racial slurs and pornographic images. A wave of emotions washed over her, among them horror, anger, and shock.

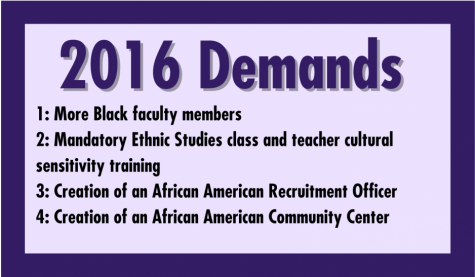

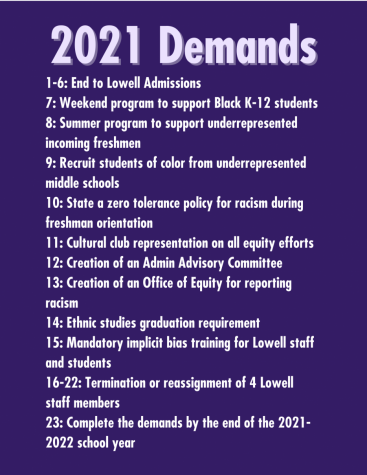

On Jan. 20 racist, antisemitic, and pornographic content was posted to the public learning platform Padlet and viewed by a number of Lowell students and staff when attempting to engage in a school-wide anti-racism lesson. In response to the incident and Lowell administration’s handling of the incident, which was in their opinion inadequate, the BSU issued a set of 23 demands to the school and the district which aim to help create a safe environment for Lowell’s minority groups. These demands were reminiscent of those that came after the walkout staged by Lowell’s BSU in 2016 where four demands were issued, two of which have been reintroduced in the 2021 demands.

LOOKING BACK

The issue of racism at Lowell is not a new one. In 2016, in response to racially insensitive posters being posted on a bulletin board and a buildup of a number of other racist incidents, the BSU staged a walkout and issued a list of four demands to the Board of Education. The 2016 demands called for more Black teachers and staff, a mandatory ethnic studies class, a full time African-American community center, and an African-American recruitment officer. It is unclear whether or not these demands have been successfully implemented.

Despite the call for more Black faculty at Lowell, those numbers have been on the decline. According to the California Department of Education’s Educational Demographics Office, Lowell currently has two fewer Black faculty members than when the demands were originally issued. Chikere says that increasing the number of Black teachers would make a safer school environment for Black students. “As part of an underrepresented percentage at Lowell, I feel like it would make me more comfortable to see teachers that look like me teach at the school,” she said. Principal Dacotah Swett said few teachers of color apply to positions at Lowell. “Where we have had a choice like that we have definitely hired for equity,” she said. Swett has also expressed optimism about this situation moving forward, mentioning that Lowell has hired a new Black faculty member for next school year.

The second BSU demand focused on education. First of all, it requested that Ethnic Studies be made mandatory for all Lowell students. While Lowell’s administration does not have the power to make Ethnic Studies a graduation requirement, Assistant Principal Joe Dominguez says that strides are being made to expand the class. Currently Lowell offers a single course of Ethnic Studies but, according to Dominguez, the school will be offering five year-long sections of the class next year. Additionally, on March 25, the San Francisco Board of Education approved a change that will make Ethnic Studies a graduation requirement starting with the high school class of 2028. Chikere is excited about this development. “I think it’s important because most of our world or history, like history classes, are made from a Eurocentric view of the past,” she said. “I think that Ethnic Studies is a wider range of history that has to do with different types of people’s backgrounds.”

The BSU’s second demand also called for cultural sensitivity training for teachers. Since 2016, Lowell’s faculty and staff have been participating in a professional development program. Teacher trainings had originally been conducted by the organization San Francisco Coalition of Essential Small Schools (SF-CESS), which sorted teachers and staff into groups where they then participated in facilitated discussions and lessons. In recent years Lowell has continued teacher and staff training, now conducted by Lowell faculty as opposed to an outside organization.

The BSU’s third demand for an African-American community center is also an ongoing issue. In June of 2016 construction began to turn the arcade into a $942,000 Student Union which is meant to satisfy that demand. However, according to Swett, state law mandates that all students must have equal access to all services so the space will be used for student club and leisure activities. According to Swett, construction of the facility is now complete, and is slated to open to students in the fall.

The final demand called for an African American recruitment officer who would work with the BSU, recruitment of Black students, and oversee the welcoming day held for incoming African American freshmen. The school implemented and filled the position, hiring Timothy E. Gray, in 2017. Lowell currently has four fewer Black students than when the position was implemented, according to a California Department of Education Database. The BSU is now calling for the termination of Gray, saying that he has not been fulfilling his job title. “He was supposed to recruit, keep track with grades, and support with scholarships but some students never received any from him,” said Aliyah Hunter, sophomore and BSU Treasurer.

From the administration’s perspective, Lowell has been undertaking recruitment efforts to diversify Lowell since 2008. When former principal Andrew Ishibashi arrived at Lowell, he decided to write letters to Black and Latinx students in the district to encourage them to come to Lowell. He also began the initiative to have Assistant Principals give presentations at middle schools with a high percentage of students who belong to demographics that are underrepresented at Lowell, something that Assistant Principals Jandro Alcantar and Orlando Beltran continue to do today. Ishibashi says that part of the reason he spearheaded these efforts was to prevent events like the Padlet incident. “During my 12 years as principal, I kind of saw the writing on the wall because Lowell definitely needed to diversify or try their best,” Ishibashi said.

MOVING FORWARD

Members of the BSU feel that the culture at Lowell and the incomplete state of the 2016 demands caused the Padlet incident. Sophomore and BSU Co-Public Relations Officer, Gabriella Grice, said that the complacency in Lowell’s culture needs to be addressed going forward. “If people don’t speak up about the things that they hear and see then students won’t be held accountable, teachers won’t be held accountable, and nothing will change,” she said. Hunter hopes that in the future people will strive to take more responsibility. “I hope to see more transparency between the whole Lowell community, transparency and accountability,” she said.

If people don’t speak up about the things that they hear and see then students won’t be held accountable, teachers won’t be held accountable, and nothing will change.

— Gabriella Grice

The ongoing nature of racism at Lowell made members of the BSU even more disappointed in the aftermath of the Padlet incident. “I know for me it was kind of sad,” Hines-Foster said. “But I also felt angry. The way I saw it was along with a lot of Black freshmen because initially I saw it when it was sent to the BSU group chat.” Chikere agrees, and said that the Padlet incident was also familiar to alumni. “I remember when we had that Black alumni mixer, they were telling us their stories and they were like ‘Oh wow, this is still going on at Lowell,'” Chikere said.

In the face of the Padlet incident, day-to-day microaggressions, and frustration with administration’s handling of racism, the BSU decided to stage a press conference on Feb. 5. The BSU, students, teachers, and other community members gathered at Lowell where speeches, performances, and the new demands were given. “It was really empowering to be in that space, to hold such a big event,” Chikere said. The 23 demands included calls for reforms to the admissions system, the creation of a number of equity initiatives, and the dismissal or reassignment of some Lowell staff.

The state of the 2016 demands and administrative response to the Padlet incident has left some members of BSU feeling discouraged about what kind of effort will be made to accomplish the most recent set of demands. Hines-Foster thought that the lack of accountability is what stopped substantial change from being made. “I feel like a lot of the stuff wasn’t completed even with the first four demands in 2016,” Hines-Foster said. Members of BSU are also apprehensive about the comparative length of the two different demands. “I mean in 2016, from what I’m seeing there’s only four [demands] that they asked for and it’s the fact that those four haven’t really been met and we have around 23,” Chikere said. The Lowell administration has said that they intend to implement the latest demands, though. “To the extent that we have control over it, yes we are committed to implementing those,” Dominguez said.

Since the latest BSU demands were issued, the SFUSD Board of Education has passed a resolution disbanding Lowell’s selective admissions process. This change has effectively addressed demands one through six, which were related to removing the school’s selective admissions process. Chikere feels like this is a promising step towards realizing the rest of the demands.

In demands seven through fifteen, the BSU calls for new initiatives to bring more racial equity to Lowell. These include programs for underrepresented students, initiatives to incorporate underrepresented students’ voices, and opportunities to educate the Lowell community on equity and culturally relevant topics.

A few of the demands center around creating opportunities for underrepresented students to give input on school decisions. These initiatives would provide student input on administrative decisions, develop a new system to report instances of discrimination, and guarantee cultural club representation on equity efforts. Maria Herrera, senior and Co-President of La Raza, has high hopes for them. “I think that giving people a platform to speak can help unify the communities at our school so they know that they have someone out there who can help them out,” she said. “I would love for these voices to be amplified to bring positive change to different environments.” Swett said that the idea is promising but likely won’t be discussed until next year. “This is the outgoing administration now. So we really don’t even have capacity to put that into place for right now but it could be something that would be done in the fall,” she said.

In order to educate the Lowell community, the BSU has again called for an Ethnic Studies graduation requirement and mandatory implicit bias training for students and staff. The school will continue to to create registry lessons that will educate students on anti-racism. However, Dominguez claims that there has been a lack of support from the district for this project, saying that he reached out to the district for resources but never received a response. The team, consisting of students, counselors, and teachers, ended up drafting the lessons themselves. “I think it’s powerful but no one of them is specifically trained on this work of anti-racism, making sure that we are properly teaching it,” he said. Hines-Foster also believes that this work would be more impactful if done by professionals. “I think we need people who are trained in the work, to do it,” she said. “You can’t really have people who don’t always see the issues fix them.”

Giving people a platform to speak can help unify the communities at our school.

— Maria Herrera

The BSU’s latest demands also call for weekend programs for Black K-12 students and a summer program for incoming freshmen from underrepresented demographics in their demands. Hines Foster says that the purpose of the summer program is to support incoming BIPOC students. “Honestly, [it’s] just to build community but also to have them be prepared,” Hines-Foster said. “I think a lot of times the kids who get in through the admissions system the schools where they come from don’t really have a lot of resources that some of the schools in other neighborhoods have.” A project is underway which will potentially satisfy this demand. Lowell’s Peer Resources, in conjunction with Summerbridge, will be hosting a two-week summer peer mentoring program for incoming BIPOC students. Peer Resources contacted Lowell’s cultural clubs for input. “They really wanted to reach out to cultural clubs such as BSU, La Raza, Poly, and Phil-Am,” Hunter said. “And they just wanted to make it so that incoming BIPOC students can feel welcome and just make a safe environment between the class of 2025 before they go into Lowell.”

The rest of the demands, 16 through 23, call for the removal or reassignment of four Lowell faculty members. Since the demands were issued, two of the four, Swett and Assistant Principal Holly Giles, have announced their intent to retire at the end of the year. As for the other two staff members, Gray and Elizabeth Statmore, Alcantar said, “Regarding the BSU’s staffing demands, the administrative team did not consider those as action items at the time, nor do we now.”

In addition to attempting to address the BSU’s demands, Lowell’s faculty and staff are making some efforts to make classrooms more inclusive. This includes continuing their professional development, having teachers set an anti-racist teaching goal at the beginning of the year, and buying literature for the English department with authors from more diverse backgrounds.

Dominguez also hopes to make strides toward incorporating more student voices. “[I want to] include all of our students in the conversation,” he said. “So making sure that when we are making big decisions, we are doing it with our Black students and our Latino students and our Asian students in mind. So it’s not just we’re assuming that we’re helping our students, we’re actually having conversations with them and we’re bringing them in and we’re listening to their insight.”

In addition to Lowell undertaking equity efforts on its own, the Education and Civil Rights Initiative is currently conducting an equity audit, as called for in the board resolution that disbanded Lowell’s previous admissions policy. According to Gregory Vincent, Executive Director of the initiative, the audit will collect information about the climate and culture of Lowell to present to the Board of Education. “We’re independent so we’re there to provide the truth using reliable, scientific processes,” he said. The first meeting of the action team made up of community leaders took place on May 12. According to Vincent, organizing focus groups and sending out surveys to the student body are the next steps. We are giving you the chance to listen to us and implement these demands. That will show us that you guys hear us and that you’re there for us and that you support us. — Aubrey Chikere

As efforts to address racism at Lowell continue, Black and Latinx students have emphasized the importance of listening to marginalized voices. “If a group that you have historically harmed, abused, neglected is coming to you saying they want something, or in this case, need something in order to feel safe, I think that it’s their duty as administrators to do that,” Hines-Foster said. Chikere also says that implementing the demands will show underrepresented students that their perspective is valued. “[Administration] being more approachable, and actually making an effort to work with us with issues like these would help,” she said.

Should the demands not be implemented, underrepresented students say there would be a negative effect on the community. “That [would] show me that they do not care about what Black students have to say,” Chikere said. “They don’t care about what we need at Lowell and they don’t care that the school needs to change.” Others have emphasized the need to hold the school and district accountable if they do not make an effort towards the demands. “I think administration does need to be held accountable,” Herrera said. “I hope that there is a reaction. I don’t know what’s going to happen because I know that there’s some kids who don’t think that everything that’s happening should be happening for some reason but there’s a bunch of support, so I hope that the support is overwhelming.” Chikere also stressed how the demands would benefit the school community as a whole. “In general I hope Lowell is a safer and healthier place to attend,” she said.

After the many events and conflicts that took place since January, cultural clubs and faculty alike are contemplating what must be done to repair relations in the school community. “For me, I’m going to continue to be present for every student that needs me,” Dominguez said. “And then just continue to listen, apologize when we make mistakes, and then be as transparent as we are allowed to be. That’s what I can promise.” BSU members also feel that the way forward is by working together to address these problems. “We are giving you the chance to listen to us and implement these demands. That will show us that you guys hear us and that you’re there for us and that you support us,” Chikere said.

Update, May 28, 2021 4 p.m.: An earlier draft of this article led readers to mistakenly believe that the jobs of Timothy Gray and Elizabeth Statmore were in jeopardy; they are not. The text was changed to clarify the situation. We apologize for the misunderstanding.

Marlena is a senior at Lowell. When she isn't at school she's probably at the lab, watching a movie, or sitting on the sidewalk listening to music (usually Björk).