Hope fuels the struggle to end Asian hate

The atmosphere in sophomore Ellie Lim’s home is thick with tension as the Chinese American family gathers to address recent events: her aunt’s direct encounter with traumatizing hate and discrimination. A white woman shoved her in Home Depot and told her to return to her own country despite being born in the United States. Lim’s family was no longer untouched by the nationwide attacks on Asian Americans. Filled with frustration and fear, they discuss measures to stay safe. This household can’t help but wonder: which one of them will be next?

Lim is only one of the numerous other Asian American students at Lowell who have been deeply impacted by the recent spike in COVID-fueled anti-Asian hate crimes.

With the initial spread of COVID-19 blamed on Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities, the ripple effect was devastating for many as targets were placed on their backs. Overwhelmed by the constant attacks and increasingly afraid to step outside, Lowell students have not escaped the emotional distress and subsequent behavioral changes resulting from the uptick in hate crimes against Asians. However, Asian Americans are banding together to raise awareness for this issue. Step by step, many believe that racism can eventually be overcome.

Recent anti-Asian discrimination has been fueled by the coronavirus. At the start of 2020, as COVID-19 began to spread around the world, many were quick to blame Asian communities because the first cases of infection were identified in Wuhan, China. Blame gave rise to hate, and xenophobia became a more prevalent issue than ever. In March 2020, former president Donald Trump escalated the situation, repeatedly referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” in public statements. “When president Trump insisted on using the term ‘Chinese virus,’ it did two things: it racialized the virus so the biological virus became Chinese, and it stigmatized the people so that Chinese were known to be the diseased carriers and to be blamed for,” said Russell Jeung, co-founder of nonprofit organization Stop AAPI Hate and department head and professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University.

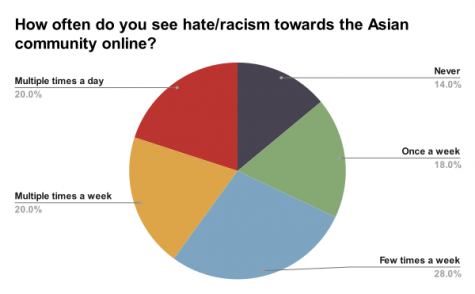

As a result of rising hate and normalization of xenophobia, verbal and physical assaults against Asians increased dramatically all over the world, including in San Francisco. On March 17, an elderly Chinese woman was assaulted on Market Street in San Francisco and hospitalized after suffering severe injuries. “Unfortunately, as a society, we’ve gotten to a place where this is at least somewhat acceptable,” said Evelyn Ho, professor of Asian American studies at University of San Francisco and a health communications researcher. Several Lowell students, who wished to remain anonymous, were verbally attacked with racial slurs. Being stigmatized in the media have also become especially common experiences. According to a survey given to Asian American students at Lowell, 24 percent have been verbally attacked for the way they look, 49 percent have seen racism online multiple times a week, and 20 percent have seen racism online multiple times a day.

Seeing these crimes on various media platforms and hearing firsthand accounts from family members and friends has caught Lowell students in a wave of emotions. It was difficult for Lim to see these ordeals curb her aunt’s optimistic outlook. “She’s usually very cheerful about everything. It made me frustrated and worried about what she was going through,” Lim said. “What she experienced has really made her annoyed in some way because this shouldn’t be happening to someone who is a specific ethnicity or race.” Sophomore Natalia Nagata was sickened by a video that she saw on social media. “This guy just came up to this woman and started punching her. Who has the audacity to do that?” she said. “I feel like I have to accept the fact that even though people say America is a free country, it really doesn’t feel free to people of color or Asians.” Sophomore Ben Chen had similar frustrations, and was particularly upset that the attacks often targeted the elderly population. “Those attackers are cowards for not attacking somebody their size,” he said. “But they obviously shouldn’t be attacking anyone either way.”

Many Asian Americans have been feeling powerless and unable to control their own safety. “Our sense of safety has been stripped from us and I think it’s very traumatic to see what’s happening,” Cynthia Choi, another co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate, said. Nagata believes that the sense of helplessness surrounding racism makes it even more frightening than the pandemic. “The virus is something we can prevent by wearing a mask, or wearing gloves, or sanitizing our hands,” she said. “But we still have this really high chance of getting shot and killed by a stranger.” Though, according to Ho, the risk of dying from COVID-19 is exponentially higher than that of being harmed by a hate crime, Ho finds it especially troubling that people are feeling this way. “I’m sad to hear that, and I also understand it because when all you see in the news is the next incident … it does make it really difficult,” she said.

For some students, both verbal and physical accumulated attacks have put a strain on their mental health. 57 percent of Lowell’s Asian Americans reported that their mental wellbeing has been negatively affected by the hate crimes. In an effort to stay educated about Asian hate, junior Taylor Tsan reads articles about the attacks and engages on social media, but the frustration can become unbearable. “Sometimes it’s too emotionally draining for me to go deep into it, and I just don’t feel like reading about some Asian woman getting beaten up,” Tsan said. “So I don’t.” In addition to seeing physical attacks, many Lowell students are also observing and experiencing verbal attacks which can be just as traumatizing, according to Ho, especially if they are repeated. “When you add that into somebody’s everyday experience, over and over and over again, the fear of that happening to you is perhaps as distressing as the thought that somebody might attack you,” Ho said.

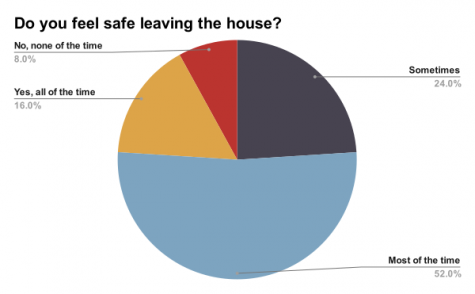

For other students, feelings of defenselessness and fear have translated into changes in their typical patterns of behavior. When Asian American students were asked if they feel unsafe leaving their homes owing to the risk of being attacked, 62 percent concurred, including Nagata. “I take walks in the mornings and sometimes I feel afraid because I saw this group of people, and they were just staring at me,” Nagata said. “They were glaring at me and I was so scared.” Sophomore Rachel Wong refrains from leaving her house as much as possible, avoids public areas, and has her parents drive her, even if it is a short distance. “I’m just scared that someone would be after me,” she said. “I would get hurt because of the color of my skin or the way that I look.” This paranoia has also affected her stance on the return to in-person learning. Seeing the constant attacks on Asian Americans, including violent shootings in the news, Wong fears assailants may target Lowell’s majority Asian population.

For others in Lowell’s community, the recent and numerous anti-Asian hate crimes bring up old trauma and serve as a reminder that racism against Asian Americans has been an ongoing problem. In 2015, AP Chinese teacher Ning Zhang was with her husband and cousin at the intersection of 5th and Market Street, when three Caucasian boys in their twenties thrust a CD into her hands and told her to pay for it. While she stood, stunned, one of them touched her cousin’s hair. Panicked and afraid, fearing the boys would harm them, Zhang quickly offered them ten dollars. “Go Back to China. F*ck you b*tch,” the boys shouted as they walked away with the money. “Why do we have to be treated like this?” Zhang said. “Even though it was five years ago, I still hold the strong emotion once I recall this memory.” Experiences like Zhang’s have happened for a long time, according to Choi. “We saw COVID being racialized very quickly because of the longstanding racist stereotypes. It’s no accident that there was this huge backlash against Chinese and Asian Americans more broadly,” Choi said. “This historic precedent is actually the reason why we started Stop AAPI Hate.”

Many Asian communities have long since been standing up against AAPI hate, but the recent hate has finally brought more attention to their struggle. “I’ve been fighting this narrative that we’ve been silent,” Choi said. “We’ve actually been speaking out at every turn and we’re finally having people listen and it’s getting the attention it deserves.” Lim has also noticed that the recent attacks have brought more attention to racism against the AAPI community, believing that taking even a little bit of action is something to be proud of. “Asian Americans are coming together as a group because of this pandemic and speaking up about what is right and wrong,” she said. “I think that’s a really big step forward.”

As anti-Asian attacks increased in severity, some members of the Lowell community have taken action by educating themselves, raising awareness by sharing presentations during club meetings and discussing their experiences amongst themselves. Several clubs, including the Political Science Club, Partners Against Institutionalized Racism (PAIR) Club, and Hapa Club, have placed an emphasis on Asian hate and held discussions about its effects on students of all backgrounds and how non-Asian students can be allies. According to Lowell Political Science Club President Win Neubarth, since the club has multiple members who have been personally affected by AAPI hate as part of the community, the club spends time during club meetings discussing potential solutions and what students can do individually to take action. “We’re going to discuss potential solutions to how we can stop all the hate that’s been going on while also discussing what we can do on an individual level to fight against the hate,” Neubarth said. “When they see what’s happening to their own people, they get scared, and for good reason.” Wong, a member of PAIR, has appreciated how the club has been a safe space to discuss how they feel about anti-Asian hate, as well as how non-Asians can be an ally to Asian communities.

Chen has decided to become politically active. Angered by the amount of hate targeting the Asian community with little being done to stop it, he requested to speak at a protest bringing awareness to AAPI solidarity and safety, organized by District Four Supervisor Gordon Mar along with several nonprofits. On April 18, Chen spoke out to over 300 San Francisco residents as a representative of the city’s youth voices, giving a speech about racial unity and ways to overcome this discrimination. “In order to solve these racial problems, I believe we need to solve the problems at the source, which starts with these racist stereotypes being spread around at the local community level,” Chen said in his speech. “We demand the establishment to take further action in eliminating the evil that is racism.”

Since anti-Asian discrimination will not simply disappear after the pandemic ends, some believe that change must begin through education. According to Choi, one form of education could be through an Ethnic Studies or Asian American studies class. She believes this would allow students to learn about the history of several ethnic backgrounds. “It’s vitally important to know our history, and not just the history of violence that our community has experienced — criminalization, dehumanization,” Choi said. “But also how we have been making this experiment, this multi-racial democracy, a reality.” Chen agrees that educating the incoming generations and implementing ethnic studies courses into school curricula is a step in the right direction to overcome racism. “Race is a social construct, right? It’s not anything biological,” he said. “I want that societal understanding across all humanity, to be able to understand that no race is inferior or superior to others.”

There are also simple actions individuals can take to bring awareness to anti-Asian hate and decrease the amount of violence. Jeung believes that people should try to stay outside when it is safe to do so. “As you have more eyes and ears looking out for grandmas, then that creates a sense of safety,” Jeung said. According to Ho, it can also be practical to engage in workshops conducted by Hollaback, a non-profit organization that provides bystander training. They work towards preventing and intervening in all forms of harassment, but currently have an emphasis on Asian hate and xenophobia. “As a person witnessing violence being done to another person or negative words being said to somebody else, you can actually feel empowered to do something,” Ho said. “[Their training] actually gives you different ways that you can engage so you don’t always have to be directly confronting somebody, but rather you can be doing some of these other steps as well.”

Despite the severity of current situation, members of the AAPI community are optimistic about the future, though they agree speaking out against hate and discrimination is key. “I feel that there’s hope,” Ho said. “I think that, sometimes when unfortunate things happen in society, they are also the catalyst that pushes people who might not otherwise have stood up before to stand up, and I do feel like you’re seeing a lot more of that now.” Students also feel hopeful. “The future, for now, looks bleak for Asians. But what gives me hope is that the future doesn’t have to be bleak if we, the youth, do something about this current crisis,” Chen said. “We, the youth, can make change in our communities. We, the youth, can take up leadership roles and put a stop to these hate crimes. Don’t just stand up, take action.”

Angela is a senior at Lowell who recently bought a membership at the Stonestown movie theater. In addition to watching movies, she loves to sing and is part of Lowell’s concert choir. Despite this and her 6 years of experience playing volleyball, her greatest skill is procrastinating.

Kelcie is a senior at Lowell who can be found in the journ room working, drinking coffee, and listening to music. Her older brother once mentioned that there are only three guarantees in life: death, taxes, and Kelcie not waking up to her alarms. She also happens to have a paradoxical relationship with chicken… go figure.