The fight to stand with survivors

Senior Justine Orgel sat on her bed, hands clenching her phone. For days, story after story of sexual assault had flooded her feed, but this story was different. This allegation was about a boy in her grade that she knew — the friend of her own sexual assaulter. Disturbed and angry, she wanted to hold the assaulter accountable for the trauma they had caused, but there was no clear way to do it.

So, she decided to create one.

After conferring with her family and weighing the potential backlash, Orgel started writing an email template that outlined the recent allegations. She hoped that the template would be used by other students as an organized way to demand an investigation into the allegations and consequences if proven guilty. She posted the template to her Instagram story and anxiously sat by her phone all night, fearing retaliation from the two boys. She only managed to sleep for two hours that night.

The issue of sexual assault and harassment at Lowell was shoved into the spotlight this past summer, when an outpouring of stories hit Lowell and the rest of the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). The stories inspired students to demand that the Lowell administration take action against the allegations and begin conversations about how to prevent future instances of sexual assault and harassment.

In mid June of 2020, survivors from Lowell and other SFUSD schools started coming forward with their stories on social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter. Every day, multiple allegations were posted, receiving hundreds of likes and reposts from students trying to spread awareness. Survivors were met with an outpouring of support from their peers, who copied pre-written templates and emailed them to the school administration and the district, urging them to punish assaulters. To keep a record of all the allegations, students also created lists of those accused.

After her first email template garnered widespread support, Orgel wrote more templates for other survivors, eventually writing 12 in total. She created a Google Form for survivors to request a template, and also reached out to survivors whose stories were widely circulated. Each template was about one accused assaulter, summarizing and demanding investigations into the allegations from the Instagram posts, and calling for those found guilty to face repercussions. Each template was fully written and ready to send, although students could add their own thoughts if they wanted to.

Students could send them to the Lowell administration, the SFUSD Office of Equity, and if the accused assaulter was an alumnus, their future college. Orgel thought the templates were an effective way for survivors to capture the attention of those with the power to hold assaulters accountable beyond online support. “You’re going to get support from the community, but after that, [you] might not know what to do,” Orgel said. “So I thought that if you flooded inboxes so all they see is emails, they’re gonna have to respond in some way.”

The email templates were instrumental in supporting survivors. Gabrielle, a survivor using a pseudonym, was grateful for being able to share her experience through Orgel’s template. “I think that other people recognizing my story and the other girls’ story, and taking the action to do something about it was really validating,” she said. Despite devising a way for others to speak out, Orgel didn’t want to come forward with her own story. “I wrote everyone’s emails and I speak out, but when it comes to my own I just never wanted to say anything,” she said. “I just wish that I had someone like me.”

However, Orgel was cautious of writing a template that promoted false allegations. The accessible nature of posting allegations combined with the fact that almost all stories were met with total support from all students made it easier for students to post false allegations. A few allegations were revealed to be false soon after being posted on Instagram. Although there was no foolproof way of confirming credibility, Orgel would look for consistent, corroborated stories with detailed incidents to report. She decided not to write templates for stories from anonymous burner accounts or ones that she had conflicting knowledge about. “I didn’t want it to be something that was weaponized,” she said. “I have a role where I feel like I’m supposed to be impartial, a little bit robotic, but the truth is I can’t do that for everyone.” After establishing credibility as best she could, Orgel would then work with the survivor to determine which details they were comfortable with including in the email template. “It felt like something with so much gravity, so important that I didn’t want to mess up at all,” she said.

The flood of emails did not go unnoticed by the Lowell administration. In an email to Orgel, Principal Dacotah Swett wrote that the administration had been briefed about one of the incidents and had referred it to the district to be investigated. “I take these matters seriously and I promise that we are working on improving the culture of Lowell and our community,” Swett’s email stated.

Another issue that came to light during the outpour of stories was survivors’ unsatisfactory reporting experiences with the administration. A few posts detailed a lack of follow through or a confusing and dismissive process, none of which surprised Gabrielle. “I feel like Lowell will often tend to sweep things under the rug, especially stuff that frames their student body or even teachers in a negative light,” she said.

Survivors’ firsthand experiences with the Lowell administration made many doubtful they would handle the allegations adequately. Crystal, another anonymous survivor under a pseudonym, was sexually assaulted off campus by a Lowell senior two years ago, and came forward to the Lowell administration hoping that her assaulter would be held accountable. Instead, she found the reporting process complicated and traumatizing. For weeks, she was pulled out of class to sit in meetings that felt directionless with Dean David Beauvais. Ultimately, Beauvais brought in Crystal’s father and told her to read the incident report of the sexual assault out loud to both of them. “[That] made me very uncomfortable because these were two grown men — especially one that I am not close to,” she said. Feeling more traumatized than she had been before reporting her story, Crystal decided to stop meeting with him and to stop talking about her experience altogether. “They kept telling me they would talk to [the student that assaulted me] and they never did,” she said. With no punishment for her assaulter, she continued to run into him every day in the hallways, which only reminded her of the trauma she had experienced.

Although he does not remember such an incident taking place, Beauvais is regretful to hear that a student felt mistreated. “I am terribly sorry that they felt that I was insensitive, I don’t remember any of that, but still,” Beauvais said. He also empathizes with survivors, recognizing that he is not the person that survivors are most comfortable confiding in. “I’m a male, I am of a certain age,” Beauvais said. “These are very sensitive issues and I am aware of that going in.”

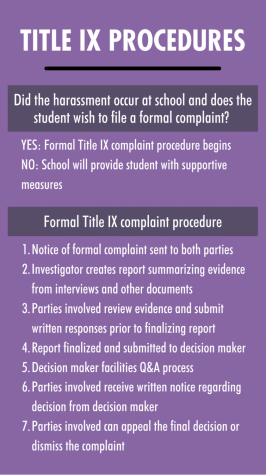

School administrators are bound by legal restrictions when responding to reports of sexual assault as barriers to enforcing punishment. According to the SFUSD website, sexual assault or harassment that did not take place at school or at a school-sponsored event does not fall under the protections of Title IX, the federal law that protects students from discrimination on basis of sex, including from sexual assault. In those cases, school administrations and the district lack the authority to suspend or expel accused assaulters.

Some advocate for punishments within schools instead, when possible. Gabrielle would like to see accused assaulters removed from school clubs and sports teams, “to show that these people shouldn’t be allowed to participate in the community.” However, according to Assistant Principal and Lowell Title IX coordinator Isaac “Jandro” Alcantar, the administration can only remove assaulters from school activities once allegations against them have been proven true and if the assault happened at school. Accused students who are still under investigation cannot be removed.

There are also restrictions on how the administration can investigate allegations. “We have a 60-day window to complete the investigation,” said Alcantar. “Sometimes [it is] not as easy to get all of the information because we have students that don’t feel comfortable, don’t want their parents to be told, don’t really want anybody to know about it.” Formal Title IX complaints are investigated by the district, and can take up to 90 days to complete. Additionally, recent changes to Title IX have narrowed the definitions of what constitutes sexual harassment, which makes it more difficult to pursue consequences for assaulters that do not fit the specific criteria.

Lowell community members are concerned that the administration’s emphasis on legal restrictions regarding sexual assault investigations may send a dangerous message. Gabrielle worries that it creates protection for assaulters. “Someone who did something like that could take that as, ‘Oh, people will just forget about these accusations and nothing will happen to me,’” she said.

The Community Equity Committee (CEC), a group of Lowell stakeholders working to improve equity, organized a virtual listening session in July, partially intended to help inform the Lowell administration’s management of sexual assault. At the listening session, students spoke about issues such as sexual assault, mental health, and racism at Lowell to nearly 200 attendees, which included Lowell administrators, Board of Education commissioners, and city supervisors.

After the listening session, the CEC planned to work with the Lowell administration to establish methods of reporting equity-related incidents, as well as requiring every teacher, administrator, student, and family to go through equity training. Students had high hopes for what the CEC would accomplish. “They got Board of Education commissioners to listen,” said senior Emmanuel Ching, a former member of the CEC. “They got city supervisors to listen. They were starting to work with administrative staff to lay out a blueprint for equity … I was excited to see where that was going just because it was nothing like what I’ve ever seen before.”

However, in September 2020, the administration disbanded the CEC because they wanted to transition to having equity work handled internally instead of by an outside organization, according to Swett. Members of the CEC were invited to apply for The Principal’s Taskforce, an entity meant to continue the CEC’s equity work. According to Swett, many CEC student members signed up, but no parents or teachers. Low recruitment and the onslaught of distance learning responsibilities led to no movement with the project. “To be honest, a lot of other things kept piling up,” Swett said. “I wanted a task force. That did not get done. That’s on me.” Swett says she plans to ramp up recruitment for the task force when distance learning ends. The lack of follow-through with the task force has left some students frustrated. “If they are going to disband such a vocal, visible entity that was fighting for change, progress, and equity, then what are they replacing it with?” Ching said. “How are they continuing the fight that the CEC participated in?”

Seven months after June, the process for reporting sexual assault at Lowell is still unclear. Every SFUSD middle and high school has two title IX coordinators, administration members specifically designated to guide students through the reporting process and communicate reports of sexual assault to the district office. Inconsistency with who holds the position at Lowell has added to the complicated administrative handling of sexual assault allegations. According to Alcantar, he and Wellness Center Coordinator Carol Chao Herring are co-Title IX coordinators. But Chao Herring says differently. “It’s Jandro Alcantar, he’s the Title IX coordinator,” she said. The 2020-2021 official list of Title IX coordinators says Alcantar and Swett are both coordinators with no mention of Chao Herring. The administration has acknowledged that their procedures around reports of sexual assault are unclear. “I think that the reason there’s the perception that there’s a lack of transparency is because we don’t have a clear process on how to report these [incidents],” Assistant Vice Principal Joe Dominguez said.

Some experts believe that making the process of coming forward as clear as possible is a good first step towards supporting survivors. According to Neena Chaudhry, an attorney who works with schools to protect women’s rights through Title IX procedure, having a standardized reporting system makes it easier to come forward. “Students have to have confidence in their school and their administrators and see that other people have come forward and that it’s been a not horrible experience,” she said. “The more schools do it right, the more confidence students have.” Chaudhry’s words were echoed by survivors. “The way [the reporting process] is now … I don’t think it would be a good experience for anyone,” Crystal said.

To combat this problem, Dominguez is working on an idea for a new system to report sexual assault located on the school website with a clear outline of the reporting process, which he hopes will help survivors feel supported. “It’s hard to report, there’s a lot of loneliness,” Dominguez said. “So I am hoping for a process that respects all of those feelings when something like this happens, because it’s traumatic.”

In addition to outlining a clearer reporting process, many believe the problem needs to be addressed at its root with more education on consent, sexual assault, and sexual harassment. “Having education and conversations, and removing shame and stigma around having these conversations, are really important to having consent culture,” Chao Herring said. This goal is shared by the Lowell administration who, moving forward, plans to create registry lessons about Title IX procedure and consent. Dominguez hopes that the lessons will lead to a stronger consent culture in the school. “I wish we were all programmed to know what was right and what was wrong but as soon as we start making those assumptions you find out that it doesn’t work,” Dominguez said.

Others have suggested that Lowell should encourage students to take Health, a class that covers consent and safe sex, earlier in high school. Because Lowell’s current policy allows students to take Health at any point before they graduate, many students take the class at the end of high school, by which time it may be too late. “I think we need to teach those things right at the beginning of [high] school or even in middle school, multiple times, because I think a lot of people truly get confused on the idea of consent,” Gabrielle said.

Chao Herring also acknowledges that sexual assault can be the byproduct of mental health issues, which is why the Wellness Center provides resources for students who have been accused of sexual assault to face the cause of their actions and learn not to do them again. According to Chao Herring, accused students are partnered with a Wellness provider, who meets with them in ongoing sessions, personalized to that student’s needs. “That supportive space to explore your actions is really important to have,” she said. Chao Herring believes that the only way that there will be cultural change is if people are given the opportunity to learn from their mistakes. Alcantar echoes the importance of rehabilitating individuals who cause harm. “It is really about trying to … hold people accountable, and getting support for those people who are making poor decisions,” he said.

Tori VandeLinde, the Project Coordinator for the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault, believes that what ultimately needs to change is the culture that excuses sexual assault. She points out that it takes more than education to rehabilitate people who understand what consent is but still choose to assault people. “All the individual education in the world is great, but if someone’s environment isn’t complementary of that or isn’t supportive of that individual education and behavior change, it’s likely not going to have the greatest impact that it could have,” VandeLinde said. Chao Herring agrees. “It’s the dynamic that’s toxic,” she said. “It’s the gender norms and the toxic masculinity and the sexism in our culture.”

While there are many proposed solutions to the issue of sexual violence, some survivors remind us that their voices need to be heard in all solutions, and that people can support survivors on a personal level by just listening to them. “Not everyone wants to deal with it the same way,” Gabrielle said. “Some people might want to talk about it, some people might want to just push past it. Some people might press charges, a lot of people do not want to. You need to listen to what the person wants and support them through that.”