Breakout rooms aren’t working—but they can

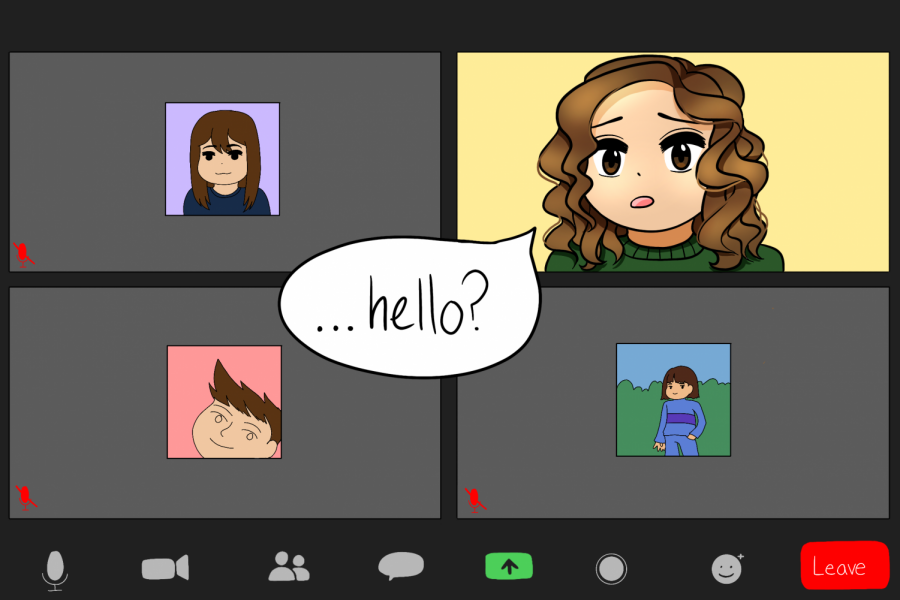

“I’m sending you into breakout rooms!” my teacher says. I click on the invite to join breakout room 6, wondering who will be in my room today. I look over their names and realize I don’t know anyone. None of them have their cameras on, so I turn mine off. I wait for a moment in silence before I venture a “hello.” Another moment passes before someone monotonously greets me in return. After a few more attempts to generate conversation, we fall into silence, and I resolve to do our work independently. At one point my teacher pops in, and three out of four mics quickly come off mute as if we’ve been participating. Upon their departure the silence returns once again.

This is not an uncommon experience.

As COVID-19 cases rapidly rise with the emergence of a new dominating strain, and SFUSD continues not to release any plans for reopening in the near future, it seems increasingly unlikely that we will be back on campus any time soon. So as we move through yet another semester of distance learning, it’s important to reflect on what is working, and what is not. And when classes are only 35 minutes long with every minute precious, too many breakout rooms simply don’t work. But they can work, if instead teachers help students feel comfortable in them by pre-assigning the rooms and taking into account student preferences as they do so.

Breakout rooms are meant to be a substitute for in-person groups or tables, but they often don’t fulfill their purpose. The difference between in-person groups and breakout rooms is that in the first, you’re forced to interact with your peers—they’re sitting right next to you. But when faced with three black squares and three mute icons, it’s much easier to stay silent. If the room is randomly assigned and no one is talking, it’s much easier to text a friend or classmate with questions rather than take a chance by jumping off mute into the cavernous silence. And then the rooms become useless. Everyone’s working on their own.

But should we just disregard breakout rooms? A few bad experiences doesn’t mean they’re never beneficial. “It is nice to have time where you’re able to talk to others, and actually share ideas,” freshman Kayla Yee said, when asked how she feels about breakout rooms in class. Small breakout rooms open up a space for students to freely talk among themselves, and can be helpful for students when struggling with the subject matter. Junior Maya Bhandari feels that it is important for students to learn from peers in addition to their teachers. “Sometimes I need the extra perspective or another way of saying the same thing in order to fully understand a concept,” she said.

So how do we make them work? Why are breakout rooms silent in some cases and productive in others? Although there are many variables, one big issue is the consistency of who we’re working with. When school was in-person, students often worked with the same people for weeks at a time. Even if we didn’t know our group mates in the beginning, we grew familiar with the people we sat with. It’s a similar situation with breakout rooms. Junior Brody Andrews has found that when the people in his group stay constant, the room is more effective because this helps students feel more comfortable with each other. “When I had breakout rooms at the beginning of the year that were preassigned, we didn’t really have our cameras on. No one talked,” Andrews said. “By the end of the first couple weeks that we had been together, we were all contributing, we had our cameras on, we all knew each other.”

Breakout rooms also tend to be more productive when students have a say in who they’re working with. When Junior Pradipti Lamar was in such a group, it was easier for her and the others to participate. “It was fine to turn on cameras and it didn’t feel weird, since [we] weren’t strangers,” she said. Consistency is very important, but it additionally helps if teachers let students choose at least one of their group mates so that they’re familiar with them from the start. Teachers who have done this usually send out a form on Google Classroom before creating groups, on which students can request 1-2 people they’d like to have in their group. Andrews agreed with the sentiment Lamar expressed, saying that although simply pre-assigning plays a big role in making breakout rooms work, the majority of his good experiences have been with people he already knew. “That makes the most sense to me, honestly,” Andrews said. “Everyone knows each other so they’re not uncomfortable to speak, not uncomfortable to turn their camera on…It’s just easy to adapt to any breakout room with people that you know, rather than random strangers.”

One teacher who’s used this method is history teacher Amanda Klein. For her, the saddest thing in distance learning is when she enters a breakout room to find everyone muted with their cameras off. In Zoom, “everyone’s really uncomfortable,” Klein said. So she’s been letting people tell her who they’re comfortable talking to in order to remove that first barrier to participation. “If they’re already ready to unmute and say something, take that first step, then the learning can happen more effectively,” she said.

Letting students choose their own groupmates does bring up some potential issues—a room of friends might just talk about unrelated topics, or inequity might arise because the students who best understand the subject matter all put themselves together, while further marginalizing other students. And that is a risk that should be taken seriously. But throwing a few students together without any guarantee that they’ll feel inclined to participate is a larger risk for everyone. If students are put in a consistent group that holds at least one person they’ve requested, the familiarity might encourage them to participate, and over time help the whole group work together more productively.

Breakout rooms don’t have to be awkward and frustrating—they can be really useful if we can just make them work. Teachers need to keep the rooms consistent by pre-assigning them, and need to let students have a say in who they want to work with. As we navigate these difficult times, we’re all trying to figure out together how to make distance learning work. So let’s take this simple solution to bring one aspect of what school used to be, building relationships with classmates, back into our daily lives.