Girls on film: The struggle to see myself in the film industry

Young women often feel unwelcome in the male-dominated film industry.

I logged onto zoom and clicked the link. I was attending a retrospective (an exhibition showing the development of the work of a particular artist over a period of time) about a highly respected director from one of my top college choices. The screen presented a panel of speakers who had worked with the director; all were happy to be speaking to the future filmmakers of the world. Each of the male speakers spoke of their techniques and fond memories, dragging out each point into a 5-minute spiel as older people tend to do. The one woman on the panel, a close colleague of the director and someone who had actually written an entire book about his films, was pushed to last. She waited happily as each man told their piece, a big smile plastered on her face no matter how dull the point. It finally reached her turn to speak, and the panel had run out of time. “It’s okay,” she said. She gave a few lines about the director’s style and her advice for us before we all logged off.

It was clearly not the first time she had experienced this treatment and it was a frightening look into my possible future in film.

I’ve been interested in film making since I was around 8 years old, and my passionate and ambitious tendencies have turned the interest into a career goal. I’ve poured countless hours into watching movies, taking notes, writing scripts, and daydreaming about the career I’m working towards. Despite this dedication and love for the art form, as a girl I’ve often felt like an imposter, like someone pretending to belong in a space.

The film industry can be welcoming, it just depends on who you are.

If you look up “best directors of all time,” a subjective and homogeneous list comes up. Out of the 50 or so to make it onto Google’s watch-list, only one woman is included. And she makes action films, a genre that is typically filled with masculine themes and imagery. The elitism and lack of space for women and femininity in the film industry make many people who don’t meet the mold of a typical director turn their back on the field. I came close.

From what I’ve observed, the film industry is one that takes confidence and a strong sense of self. When communicating with harsh critics or pretentious movie lovers, one can be easily shaken by not knowing the same directors as others or not working on as many projects. I think that boys, specifically straight, white boys, are raised to be sure of themselves in a way others are often not. They are told that they are important, that their ideas matter. As a young kid, I too was headstrong and full of confidence, that I would go to Lowell High School, attend college in New York City or Los Angeles, and eventually become a director.

But, as I transitioned into middle school and faced the realities of self image as a teenage girl, my ability to believe in myself began to dwindle. Acne and awkward height began to rise to the forefront of my adolescent brain, as it does for many people of the age. What started as a hatred for my appearance grew into insecurity with my personality, then intelligence, then talent. I no longer believed I could get into Lowell, let alone become a film director. I felt that if I even tried, someone would stop me and say, “You’re not supposed to be here.” This was something I saw in most girls my age, some facing it earlier than others. Boys aren’t exempt from insecurities or other difficult feelings, but the gap in self assurance and the differences in where these problems come from is important. Where boys may feel insecure because of life experiences and other external sources, girls will feel self doubt simply because of the expectations society has of their gender. They are told, before anything else, that they should be pretty and likable, and if they don’t meet this goal, how are they supposed to believe they can meet any others that will follow? Being confident and sure of yourself as an adolescent girl is designed to be difficult, and entering a field that requires this confidence can feel impossible.

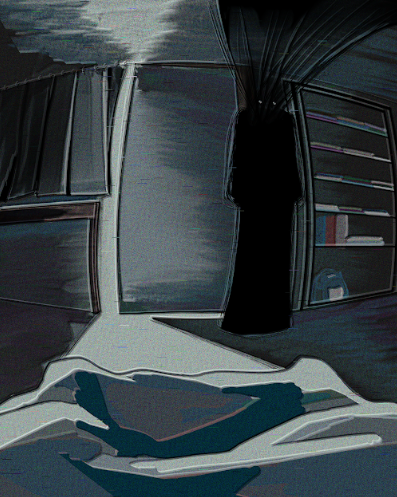

With film specifically, I didn’t feel encouraged or welcomed by the industry in front of me. I saw sexual assault allegations and manic pixie dream girls representing all women on screen. Because of the lack of women being heard in the industry, the portrayal of a woman is usually unrealistic and carries a misogynistic perspective. If the Woody Allens of the world are making the biggest movies, then of course the female characters we see on screen will be what men want them to be: the innocent girl we praise, the slutty girl we demonize, the romance between a man and a female version of himself—minus any strong opinions. I saw typically masculine movies being celebrated, while those made for teenage girls were deemed distasteful or boring or “basic.” If a woman is going to be recognized for the movies she makes, they have to be groundbreaking—something that a male director would be praised for. I wasn’t being told by myself or the world, at this time, that I could make anything like that.

Despite my warped perception of my abilities, I did get into Lowell. That was a wake-up call, like someone telling me that I was supposed to be here. Combined with growing self-esteem for my appearance, the chance to reinvent myself at a new school allowed me to see my strengths more clearly. I swore that never again would I dumb myself down or dismiss opportunities before they were even presented to me. I started trying different forms of writing, testing which would amplify the voice that I almost lost.

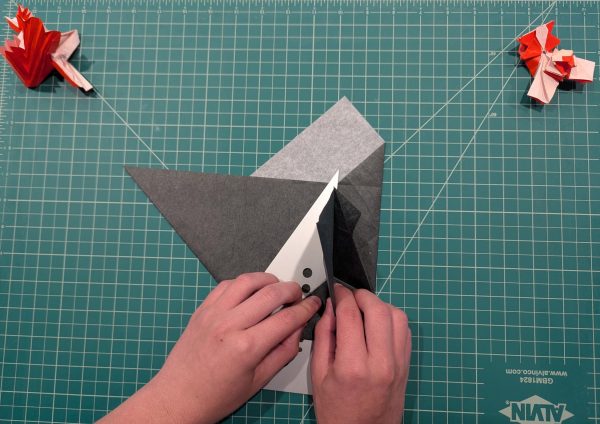

During quarantine, I, like many others, had a lot of time to reflect on what makes me happy and what I want to do in life. Through new projects, screenwriting class, and a deep look at the times when I’ve felt the best, I decided that film was still the outlet that made me happiest—that I was done following unfulfilling paths. I looked at the people who do try to become directors or screenwriters and asked myself, what do they have that I don’t? If there isn’t space for femininity, I’ll do my best to make some. I am deserving of a chance and a way to share my perspective. No one, myself included, should be able to take that away.