Special education teacher makes history as first blind person to kayak from Europe to Asia

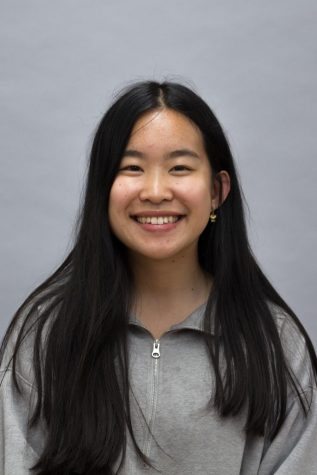

Photo Courtesy of Ahmet Ustunel

On July 21st, 2018, Ahmet Ustunel made history as the first blind person to kayak from Europe to Asia.

Oh my god, how am I gonna do this? Is this even possible? These thoughts ran frantically in part-time Lowell special education teacher Ahmet Ustunel’s mind as he prepared to kayak across the Bosphorus Strait on July 21st, 2018. Initially, Turkey’s Coast Guard Command had promised him 90 minutes to kayak from Europe to Asia, but the unexpected traffic that Saturday afternoon meant he only had half an hour for his journey. “It was really high pressure,” Ustunel recalled. “It was the fastest I paddled in my life.”

That day, he made history as the first blind person to kayak from Europe to Asia. One other thing: Ustunel is blind.

Ustunel, 40, had been preparing for this day since August 2017, when he became one of three inaugural recipients of the Holman Prize for Blind Ambition, an annual international competition that awards funding to three blind individuals to pursue special projects. Ustunel’s project was to create a semi-robotic navigation device to help him solo kayak across the Bosphorus Strait.

Ustunel lost his sight at age three due to a rare eye cancer called retinoblastoma. He is totally blind and can’t see anything, so he relies on his other senses and a white cane to guide him wherever he goes. Through this project, he hoped to “make something really cool to inspire people, be a good representative of blind people, and show the sighted community what can be done.”

Ustunel’s dream of traveling across the Bosphorus Strait stems from his experiences growing up near water in Istanbul, Turkey. As a kid, he spent a lot of time swimming, fishing, and boating around the Bosphorus Strait, a waterway straddled by the city of Istanbul. To navigate the ocean, he used radios as an audio beacon. He placed the radio on land and followed the sound of the music to find his way back onshore. As he continued spending time in the ocean, he imagined that he would one day cross the Bosphorus Strait on a boat. Learning about the story of Phineus, a blind king who guided sailors in the dark from Bosphorus to the Black Sea, in high school further propelled Ustunel’s dreams. “When I read his story, I was like, ‘Wow I should be the next Phineus, I should be the guy doing this,’” Ustunel said. “It was like a childhood dream.”

It was like a childhood dream. — Ahmet Ustunel

Ustunel didn’t realize the deep-seated impact of his childhood experiences until nearly three decades later. In 2007, he discovered Environmental Traveling Companions (ETC), a nonprofit that makes outdoor adventures accessible to people with disabilities and under-resourced youth in California. Through the program, he was invited on a kayaking trip to Angel Island. Though he had never kayaked before, Ustunel decided to give it a try and loved the experience because it allowed him to feel close to the water, just as he had in his childhood. “Your body is wrapped in that kayak, so you can control it with your legs, movements, and hips, so you feel every little movement of the water,” he said. “You are very close to the water. It’s kind of like being a turtle with a shell upside down. You feel every little thing. I loved it.”

Ustunel has come a long way in his kayaking journey since that trip to Angel Island. After receiving the Holman Prize in 2017, he connected with an AT&T engineer named Marty Stone, who had been working on an Internet of Things (IoT) powered device that uses audio buzzers to notify blind rowers which direction to paddle. After hearing about Ustunel’s ideas to expand on the navigation tool for his kayaking project, Stone was eager to help out. With a little less than a year to develop the device, the pair got straight to work.

As the project expanded, Ustunel and Stone recruited other volunteers to help build the device. The gadget went through multiple stages of development, changing until the very week that Ustunel was scheduled to complete his trip. Though the device started as a simple course navigator, it evolved as they added features like obstacle-detection and collision-avoidance sensors. Today, the pair are still working to improve the device so that other blind rowers can use it.

While Stone was building the gadget, Ustunel trained daily. He kayaked two or three times a week for 12-hour sessions, sometimes paddling up to 35 miles a day.

The preparation leading up to his trip on July 21st was grueling, but he was determined to do his best thanks to the overwhelming support he received from the community. “Whoever I talked to, they were like this is so awesome, we want to be a part of this,” Ustunel said. “I didn’t expect that much interest or support from other people, but when I got more and more support, I felt like oh my god, this is getting bigger. I cannot fail, I have to be doing this no matter what.”

On the day of the trip, crowds of people flew to Istanbul to support Ustunel, from engineers and media outlets to his 80-year-old grandma.

Prior to his trip, Ustunel encountered numerous challenges with different government agencies. Groups like the Coast Guard Command and Traffic Control didn’t feel it was safe for a blind person to kayak across such a busy body of water. “They said, ‘What? You’re like a squirrel trying to cross a highway, it’s suicidal, don’t do that,’” Ustunel said. “[Bosphorus Strait] is the second busiest shipping lane in the world, so it’s a very hectic and chaotic environment. They were trying to convince me not to do it.” In the end, the teams granted Ustunel permission with the condition that he only takes up to 90 minutes.

The day of the trip was exciting but stressful for Ustunel. Minutes before he was scheduled to begin kayaking, the Coast Guards told him he only had half an hour to cross the Bosphorus Strait, as traffic congestion was unexpectedly higher than usual. Despite the time constraints, he did better than he thought, even stopping midway to enjoy the beauty of nature around him. “Europe was in front of me and Asia was behind me [as] I drank my water and just chilled for a couple of seconds,” Ustunel recalled. “I heard a bunch of seagulls around me. It was so nice. It was the only relaxed, chill time during the crossing.”

When Ustunel finished paddling across the Bosphorus Strait, he felt tremendously fulfilled. As he neared the shore, he heard waves of people cheering him on, from engineers and media outlets to his 80-year-old grandma who traveled 500 miles to support him. “I made it and I didn’t disappoint all the people,” Ustunel said. “I was so relaxed and proud and happy. It was a really good feeling.”

Despite the challenges he faced, Ustunel persevered. He exhibited unwavering enthusiasm and grit as he embarked on his mission to kayak across the Bosphorus Strait. Along the way, he learned some important life lessons that he hopes to share with other people. “If you have a dream, don’t wait too long,” Ustunel reflected. “Start from somewhere, just start rolling the ball and it will gain momentum. Every little failure is a good step for a bigger success. If you run into problems, don’t think that they are big obstacles. Those are good learning experiences.”

Reflecting on his accomplishment on the Bosphorus Strait, Ustunel believes this experience is just the beginning of his adventures. As kayaking is his lifelong passion, he will continue to do what he loves every day. “It’s something to look forward to,” he said. “When I finish kayaking, when I pack my stuff and come home, I start thinking about my next journey.”

David Yuan • Dec 13, 2020 at 6:15 pm

This is a very inspirational story. Kudos to both Crystal Chan and Mr Ustunel!