Mental Health: A difficult conversation

“Come in, sit down, be comfortable!” a Wellness Center therapist eagerly instructed. May, a senior who requested to use a pseudonym, tentatively curled herself into the corner of the office’s couch, her hand gripped tightly around her referral slip.

Despite years of struggling with general anxiety disorder, this session last school year marked the first time May received support from the Wellness Center. A survey conducted by The Lowell found that approximately 36 percent of Lowellites either believe they have a mental illness or have been diagnosed with a mental illness, yet fewer than nine percent of the student body are receiving professional help with their mental health. These statistics stand at odds with recent school efforts to increase student mental health support, begging the question: what barriers are preventing students from using mental health resources?

May’s journey with mental health began in the fourth grade, when school social workers supported her through early struggles with anxiety. Through the following years, May would avoid situations that brought her anxiety; when she couldn’t, her “nerves,” to use the term she uses, could largely be soothed with deep breathing and calming words. However, May’s condition abruptly worsened in high school, coming to a head during her junior year. Suddenly, May was facing full-blown panic attacks that kept her awake until 5 a.m. These panic attacks also hit before classes, often forcing her to leave school early, and, on some days, not come to school at all. May began isolating herself from her friends and quitting her extracurriculars — anxiety was controlling her life.

When May was at her lowest points, the rigor of Lowell’s academics contributed to her deteriorating mental health. “[Lowell students] focus more on staying up writing an essay while pulling an all-nighter and drinking Red Bulls than sleep, healthy eating, and exercising,” May said. Falling into this familiar pattern served to compound May’s existing anxiety.

This pursuit of academic excellence over physical and mental health seemingly pervades the campus. According to The Lowell’s survey, over 70 percent of students believe that Lowell is not a healthy environment for student mental wellbeing. Teachers have also recognized this destructive mentality. “There’s almost a certain pride here about the level of stress,” social studies teacher and Lowell parent Lauretta Komlos said. “That makes me worry about my own kids, about my students.”

Despite the shared stress Lowellites experience, mental health is still a taboo topic. The Lowell’s survey found that 14 percent of students have never heard peers mention their mental health, and another 22 percent have overheard such conversations on only one or two occasions. Discussions around self-care and mental wellbeing have not been normalized at Lowell, which Wellness Center Coordinator Carol Chao-Herring believes discourages students from reaching out for help. “[Some students] feel a responsibility to look and be happy so that they don’t worry friends and family,” she said. “In a culture where we wear a lot of masks and aren’t able to take them off and be vulnerable, it makes it more difficult to seek help.”

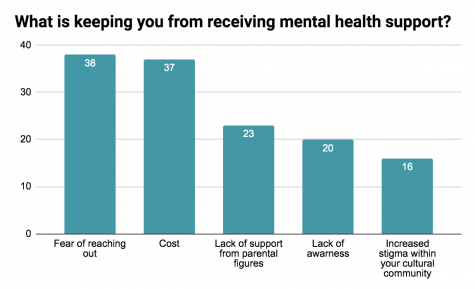

Fear of reaching out is the most common barrier keeping students from receiving mental health support (Data from a random survey of 358 students conducted by The Lowell in January 2020)

When May’s anxiety worsened last year, she knew she needed support, but the vulnerability of reaching out was daunting. The lack of a school dialogue around mental health on top of negative experiences with middle school therapists caused her to worry that her panic attacks would be dismissed as insignificant or imaginary. “I thought they wouldn’t think it was serious,” May said. “I told myself, ‘I am just panicking over going to school, they’ll think this is a stupid reason to be panicking, they won’t understand.’”

May finally made it to the Wellness Center after intervention from school staff. May’s AP Psychology teacher Alice Kwong-Ballard, who she considers to be her “safe-person” at Lowell, recognized the severity of May’s anxiety and wrote her a referral to the Wellness Center. “Ms. Kwong was the catalyst to the journey of getting help,” May said. “If she didn’t reach out and help me, then I probably still would be in a lot of mental stress and pain.”

Kwong-Ballard’s efforts demonstrate the vital role many Lowell teachers play in identifying and supporting students struggling with their mental health. Every year, teachers are required to complete an online training on how to recognize warning signs of self-harm or risk for suicide among students. Whenever Komlos identifies a student who might be struggling, she refers them to the Wellness Center or contacts their academic counselors. Some staff members, like math teacher Robert Tran, go beyond the action plans from the training, and use creative tools to check in on student well-being. Periodically, Tran asks his students to write him letters on how they are doing outside of class. These letters give him insight into the stress they are under from other courses, extracurriculars, and home responsibilities and have led him to prompt some students to see counselors at the Wellness Center. “I’ve tried to remind them that their health (physical, mental, and emotional) comes first,” Tran wrote in a statement to The Lowell.

While teachers can help to break through mental health stigma born out of Lowell’s competitive academic environment, stigma rooted in culture is a barrier less easily addressed. According to Lowell’s 2017-2018 school profile, the student body is over 56 percent Asian. The Asian American community’s unique, complex relationship with mental health can be an elephant in the room when discussing students’ hesitance to utilize available resources.

The disparities between which demographics visit the Wellness Center are significant. According to a 2018 survey of 971 San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) students by the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), an advocacy group for San Francisco’s low-income Chinese community, almost all students of color were less likely than white students to utilize SFUSD Wellness Centers — Asians being the least represented minority. While increased health risks might contribute to the overrepresentation of African American, Filipinx, and Latinx youth in Wellness Centers, a 2013 study using data from the 2007 SFUSD Youth Behavioral Risk Survey attempted to control for these variables and still found Asians to be underrepresented.

The CPA believes that this difference is partially caused by the “model minority” myth which portrays Asian Americans as monolithic, introverted, and high achieving. In its 2018 survey’s published findings, the CPA wrote that this myth “invisibilizes the stories and struggles of many young Asian American people who may internalize behaviors and disorders, such as depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation.”

Further attention has been brought to the Asian American community’s relationship with mental health in the wake of 2009 and 2015 suicide clusters at Henry M. Gunn and Palo Alto High Schools. Half of the students who died were Chinese American, motivating the school district to fund more outreach programs and partner with the Stanford University Department of Psychiatry. One program that came from this effort is Stanford’s “Asian Family Vignette” project in which psychologists perform skits for Asian parents that model healthy communication skills to use when discussing mental health with teenagers.

The program’s founder, Rona Hu, a Stanford clinical professor with a focus on cultural psychiatry and Asian American issues, believes that some Asian Americans harbor a stigma against mental illness due to generational trauma. Many Asian immigrant families have experienced war, famine, and extreme poverty, harrowing experiences that Hu has seen some get through by using denial as a coping mechanism. According to Hu, this trend can lead to parents downplaying the significance of the problems their children face and deeming discussions about mental health “self indulgent.” May, who is Japanese American, has observed this issue at Lowell. “There are families that are really understanding, but there’s definitely a stigma among Asian American families about being able to open up about mental health,” she said.

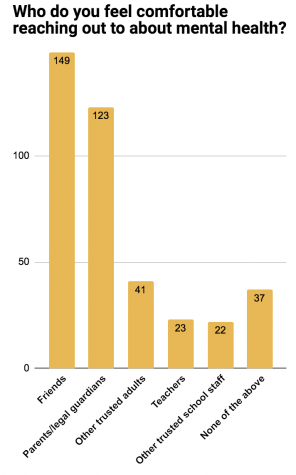

Less than 35 percent of survey takers felt comfortable discussing mental health with their parents or legal guardians.

The Lowell’s survey revealed that 20 percent of Lowellites consider a lack of parental support, not just for cultural reasons, to be a key barrier standing between them and mental health resources. Early on, May’s parents’ ignorance regarding her panic disorder kept her from care and support. “When I would panic, my parents were like, ‘Just breathe and stay mindful,’” May said. “What does that even mean? They didn’t even know what that meant.”

Lowell administrators have recently launched efforts to increase mental health awareness among parents. On November 6th, around 200 parents attended a “Family Mental Health Training” organized by administration, SFUSD crisis responders, and Chao-Herring. After presenter Kevin Gogin, a director of SFUSD school health programs and the point person for Crisis Response at SFUSD, explained statistics on SFUSD teen suicide, it became clear just how uninformed parents were over what resources are available to their teens. One parent asked, “If one in 12 students have attempted suicide [in the past year], what is SFUSD doing to address this problem?” Another parent inquired as to why they had never heard of the Wellness Center before.

This lack of awareness about the Wellness Center has serious ramifications given the essential role it plays in connecting students to outside mental health services. According to The Lowell’s survey, 30 percent of students were not aware that they could sign up for counseling services or refer other students to the Wellness Center. These services are what gave May the referral necessary to see a therapist in her insurance network, allowing her to be diagnosed for the first time with general anxiety disorder and panic disorder. With a diagnosis, May has access to cognitive behavioral therapy and medications that have significantly improved her mental health.

Without Wellness Center referrals, outside therapists can be out of reach for many students. Data from The Lowell’s survey revealed cost to be the second most common factor keeping students from receiving help with their mental health. The Affordable Care Act mandates that all insurance plans must cover mental health care, but bureaucratic hurdles often cause those with insurance to opt to pay out of pocket. The bill for a single talk therapy appointment in the Bay Area ranges between $150 and $200, according to KQED. This price can be a significant burden, given that Lowell’s 2018 school profile states that 36 percent of Lowell students are eligible for free or reduced meals based on Federal income guidelines.

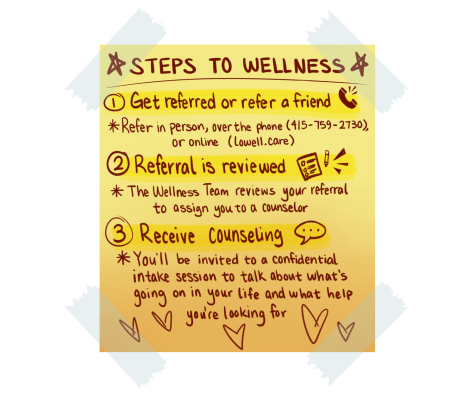

The process to see a Wellness counselor is simple, but many students are not aware that they can refer themselves or a friend to see a therapist at school.

Students’ whose families cannot afford private therapy have the option of appointments at the Wellness Center itself, but these too can be difficult to secure. Lowell is the biggest high school in SFUSD; yet, according to the 1999 San Francisco Wellness Intitiative’s 2017 update, Lowell’s Wellness Center has fewer support groups and community partners and a staff roughly the same size as that of every other SFUSD school, with two full-time therapists and interns serving 2,900 students. Still, this is an improvement since when Chao was first hired, when the team was less than half this size and the center itself was largely unheard of by the student body. “If you ask students who graduated around 2011, a lot of them won’t know that they had a wellness center,” she said. Nevertheless, the center’s staffing shortage can mean longer waits for in-school therapy, or referrals to see therapists who work for the center’s partners during outside hours.

Chao-Herring recognizes her staff is thinly stretched, so she has been teaming up with the wider Lowell community to help dismantle the aforementioned barriers keeping students from accessing mental health support.

In November, the Wellness Center partnered with Lowell’s Mental Health Awareness Club (MHA) and administration to stage a “Wellness Week” on campus. MHA, founded by senior Stella McGinn, works to dismantle mental health stigma on campus. “If there is no discussion, there is only darkness,” McGinn said, describing the club’s efforts to encourage dialogue around mental health. MHA helped organize the week full of self-care mantras, daily health challenges, and community-building art pieces on the catwalk, and following its success, Principal Dacotah Swett hopes to make this event an annual, destigmatizing tradition at Lowell.

Swett and other school administrators are looking into other avenues to improve student mental health. According to Swett, they are considering adjustments to the school schedule, an increased mental health curriculum, and collaborations with outside organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness to bring mental health tools to students. Additionally, administration held a professional development course in November focussed on suicide prevention and support for teachers for staff members.

In order to address the imbalance in Wellness Center attendance, the Wellness team is collaborating with the Chinese Progressive Alliance to bring more outreach to students. Wellness workers are using a CPA needs assessment of Lowell to develop new programming to serve students who are not currently accessing their services, and the district recently approved Lowell’s request to hire a temporary full-time wellness outreach worker. This coordinator will partner with clubs and peer leaders to educate previously unreached demographics about Wellness Center opportunities. Lowell’s Wellness team hopes that the new programming they develop will serve students who are not currently accessing their services.

Both Chao-Herring and McGinn know that sometimes, more serious conversations are left in the hands of students. Because teachers and Wellness counselors are all mandated reporters, or professionals who are legally required to report any suspicion of attempts to hurt oneself or another, some students fear sharing their struggles with self-harm or suicidal ideation with adults who can help. Several times, McGinn has faced the experience of supporting friends who were struggling with suicidal ideation, or thoughts or plans to take one’s own life. She went to the Wellness Center for help. “It’s scary,” she said. “It’s really hard being on the outside of it, but you have to be there for them.” For students in this situation, Chao-Herring recommends that they turn to the Wellness Center for professional advice to support their friends, where they won’t be forced to report their friends’ names.

Chao-Herring hopes that students will begin conversations about mental health among themselves.

When a student doesn’t feel comfortable referring a friend to Wellness Center, Chao-Herring hopes they will begin a dialogue themselves. “Just saying ‘I noticed’ without judgement, and really giving the person space to open up can really help, ” she said. McGinn recognizes that speaking up in this way requires effort, but believes the temporary discomfort is worthwhile. After losing a friend to suicide two years ago, she found an outlet among her friends and family to speak up about her own depression and anxiety. “At first it was difficult, but after breaking through and starting to talk about it, it’s relieving,” she said.

May also encourages students to speak up about their mental health, creditting opening up to friends as a major turning point on her journey towards improved mental health. “It’s scary, but it’s not a completely scary thing because we do have resources,” she said. “Once I started talking about it more, I noticed people would be like, ‘Oh, I have this too!’ It’s nice to know that there are other people.”

Having navigated her mental health maze, May now receives the support she needs from her peers, parents, the Wellness Center, and outside resources. “I went through the worst time of my life, but I’m okay now,” she said. “I thought it was never going to end, but I’m still here. Go get help…If you feel like you’re the only one who has this problem, you’re not the only one.”