Eucalyptus Drive shooting prompts students to reevaluate school safety procedures

A shooting across the street on Eucalyptus prompted the school to go into lockout procedure on Oct. 25, leaving many students confused and wondering how prepared Lowell is for these types of situations.

As seventh block begins, Dylan Lukanovic sees a fellow senior running down the hall of the main building, ordering students to get inside. As his class hunkers down in preparation for a lockdown, he also spots policemen running down the lane on Eucalyptus Drive, chasing after something. He then hears assistant principal Orlando Beltran’s announcement over the PA: “Attention all students, lockout.” Fifteen minutes later, the lockout is lifted with no explanation.

The general uncertainty surrounding the cause of the lockout and the resulting procedure led many Lowellites to reevaluate how prepared the school actually is for a shooting. Many students, like Lukanovic, did not know what they were supposed to do because they had never before heard of a lockout — where students and staff are kept in the building but classes continue as normal — let alone been trained to deal with one. Most had only heard of a lockdown, where lights are turned off, curtains are closed and all activities are paused. Additionally, students didn’t know what they were even responding to.

Around 2 p.m. on Oct. 25, Lowell was put under lockout procedure after a fatal shooting occurred across the street on Eucalyptus. The lockout lasted for about 15 minutes. All exterior doors were locked and students were told to stay inside their classrooms. Security guards entered some classrooms to lock doors, but classes were told to continue as usual. With no follow-up from administration about what happened, students were left wondering what happened, even after the lockout was lifted.

As part of lockout procedure, all exterior doors were locked in order to keep students and staff inside the building and keep everyone else out.

For many students who were not already in a classroom at the time of the shooting across the street, the lockout was very confusing. Senior Brandon Martinez, whom Lukanovic saw in the hall, was with his friends in the courtyard during his free block when a security guard shouted at them to get inside. With no idea what could be happening, except that there could be an active shooter, Martinez began ushering students on the first floor into nearby classrooms. He learned from someone else that police officers had been spotted chasing a shirtless man down the path alongside Eucalyptus Drive, but even then had no idea what was actually happening or how Lowell was involved. It took until Martinez returned home for him to realize what had happened. He heard from social media posts and family members that there had been a fatal shooting just across the street.

Many other students’ confusion stemmed from not being conveniently in the main building, within range of the PA system, when the shooting happened. Sophomore Leah Cochrum was out on the football field, participating in her PE class when an administrator came outside and ordered the class to get inside, as other classes had already done. They were hurried into the locker rooms and told to wait there, with neither teachers nor students knowing what was going on. “I feel like [administration] should have at least informed the teachers about what was going on,” Cochrum said. “They had no idea. They didn’t know what we should prepare for and we were all like, ‘What the heck is going on?’”

Students also found fault with the fact that when the lockout was officially lifted with an announcement on the PA, still no explanation was given. Twenty minutes before the block ended, Cochrum’s class was let out to resume class with no further instructions or additional information on the lockout. Cochrum only heard what the lockout was about from peers during eighth block, not from any school-wide announcement, and she felt it was irresponsible for the school administration to not offer such an announcement to the student body. “If there was an emergency or something, I want [administration] to specify what it was,” she said. “I feel like if we’re not informed, that’s a disservice to us.” She had also never heard of a ‘lockout’ before and wished the school had told her what is.

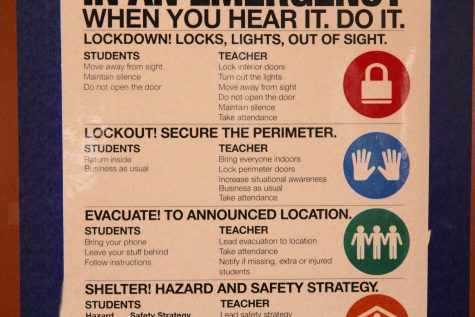

Beltran was in agreement that the procedure wasn’t as clear as it could be. While there is an official lockout procedure included on the white “IN AN EMERGENCY” posters hung throughout the school, many teachers and students like Cochrum had not heard of lockouts and mistakenly launched into lockdown procedure after the PA announcement instead. “I think we focus so much on lockdowns that the lockout was new to our staff,” Beltran said. “It’s just basically go on teaching as if nothing ever happened and we just lock the exterior doors.”

Posters such as these are posted around the school and outline lockout procedure.

However, there wasn’t much administration could have done to inform the student body of what was happening as they themselves were not fully informed. At the time of the shooting, a few teachers had seen police cars outside, and the police officers told Lowell staff to keep everyone inside, according to Beltran. Administration thus decided to institute lockdown. Beltran himself only knew that someone had been injured across the street, and got the rest of the information from other news sources later on.

Many students, like Martinez, thought that given what the school knew in the moment, the school did an adequate job of keeping the students safe. He had both heard the PA announcement and been alerted by a security guard. “The school was pretty clear that it was a ‘lockout’ — so keeping someone outside, not letting them enter the school,” he said. “I think they were as clear as possible.” Because the school and SFPD are not connected, Lowell couldn’t have immediately known what was happening, Martinez said.

Both Cochrum and Martinez, however, felt that the Lowell population could do with more frequent preparation and training, so that they don’t become complacent. While many students consider Lakeshore, the neighborhood Lowell is in, to be very safe, according to crimemapping.com, there were 436 reported crimes in a half-mile radius from Lowell in the last 180 days. Due to the students believing that they go to school in a relatively safe neighborhood compared with some other SFUSD high schools, Martinez felt that no Lowellite really expects for a shooting to occur near campus, and thus they aren’t prepared when one does happen. “Shootings are becoming [frequent and our preparedness] is kind of below standard,” he said. When Martinez was telling students to get inside classrooms, he initially wasn’t taken very seriously. “You know how at first we tend to think it’s not that serious and it’s just a joke, just like [with] fire alarms,” he said. “I guess nowadays we’re just so desensitized.”

Cochrum wanted to see more training and education for students on what to do in different situations. Instead of the same lockdown drill where everyone is in a class setting, she wanted to know what to do if she was perhaps in the hallways, or out in PE like on Thursday. That way, there wouldn’t be another situation like hers where her PE class was the last to know that something potentially fatal for the school was happening.

While the way in which the school handled the incident may have been limited by the administration’s own knowledge of what was going on, students like Cochrum and Martinez agreed that more preparation in general would be better for the current American school climate, where to them, school shootings seem to appear on the news more and more. In order to keep students safe in the event of a shooting, they wanted more universal training and communication between the school and students. While the thought of a shooting at Lowell is unthinkable to many, if one happens and students are caught in the second floor hallway or right in the courtyard, unsure of what to do, it could prove disastrous.