Finishing the fight for Ethnic Studies

Komlos speaks to her Ethnic Studies class.

“On strike! Shut it down!” rings in your ears, chanted by hundreds of San Francisco State University students rallying around you. Protesters are being arrested by the police and tear gas engulfs the figures around you, stinging your eyes and clouding your vision. One police officer punches an African American student square in the face. The year is 1968, and you’re on strike with the Third World Liberation Front and the Black Student Union. Your demand: a class that amplifies the voices of ethnic groups that are often ignored in retellings of American history.

Half a century later, the spirit of the strike remains alive in a high school elective course called ethnic studies. The class assists students in developing a newfound understanding and respect for minority groups, many of which have undertaken important roles in our nation’s history, yet continue to be overlooked by a multitude of Americans. Here in San Francisco — the birthplace of the movement — it is time to reaffirm our commitment to diversity and make one semester of ethnic studies a San Francisco Unified School District requirement for high school graduation.

Since it was first offered in the 2015-16 school year, Ethnic Studies at Lowell has transformed students’ knowledge of the struggles of minorities through examining different perspectives. This school year, 17 students are enrolled in one block of Ethnic Studies at Lowell, which is taught by history teacher Lauretta Komlos. Komlos aims to make the class a safe place for students to voice their opinions about controversial topics and personalizes lessons to encourage student engagement. Junior Dalya Deuss, who is currently enrolled in Ethnic Studies, recalls an assignment in which students were advised to bring in articles for a class discussion. She chose a video about two Saudi sisters fleeing patriarchal Saudi Arabia, where they faced homophobia, abuse from their father, and the oppressive guardianship system. The video was analyzed in class, causing students to realize and express gratitude for the civil rights enjoyed in America that are usually taken for granted. Deuss also remembers a class conversation about racial identity and how that colors your personal experiences with hardships. “I didn’t really think in depth about race before coming into the Ethnic Studies class,” Deuss said. “When you’re hearing about [the struggles] of someone, it definitely inspires you to do something about it.” This type of honest dialogue and confrontation of personal experiences between multiracial students is crucial to fostering an attitude of acceptance and appreciation of other cultures that are not your own. Sophomore Samuel Lawrence, who is also a current Ethnic Studies student, believes this is valuable because it gives everyone’s opinions a chance to be heard. Open, respectful dialogue between peers leads to a new understanding of one another, resulting in self-realization. “It’s important to understand the views of other people,” Lawrence said. “[Ethnic Studies] puts a new light on yourself, [and] it really opens your eyes.”

I didn’t really think in depth about race before coming into the Ethnic Studies class,” Deuss said. “When you’re hearing about [the struggles] of someone, it definitely inspires you to do something about it.

— Dalya Deuss

Making Ethnic Studies a graduation requirement would spread these ideas to students who normally wouldn’t have taken the course. Senior Elsie Karlak, who took Ethnic Studies last school year, appreciated the impact of a class project that compared Malcolm X’s and Martin Luther King’s methods of protesting. “It really helped me understand why some consider a more aggressive approach rather than a nonviolent one,” she said. Despite not completely agreeing with either side, Karlak questioned her long-standing opinion on the “right” way to create change as a result of the project. Another senior, Lucas Wylie, who was in Karlak’s class, appreciates the different viewpoints that the class highlights. “At the beginning of the year, there were a lot of partisan arguments that made everyone mad,” Wylie said. “But towards the end of the year, we had a debate [that] was thoughtful and everyone, while still defending their own points of view, listened and considered everyone’s argument.” As Caucasian students in a class that focused on the experiences of minority groups, the course helped both Karlak and Wylie to recognize and comprehend the struggles of those groups — struggles that they don’t experience first-hand.

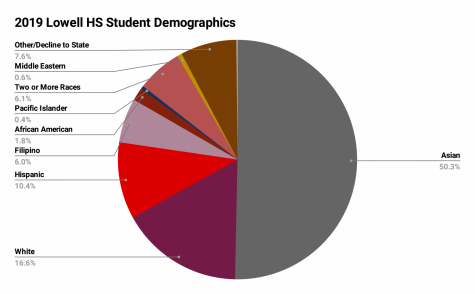

It’s no secret that Lowell is not ethnically diverse. During the 2018-19 school year, over 50 percent of Lowell students were Asian-American, according to data provided by Lowell High School. In contrast, African American, Hispanic, and Filipino students accounted for less than 19 percent of the student body. This disparity is staggering, and these groups lack representation in our student population, which an Ethnic Studies course would provide.

Data courtesy of Lowell High School.

However, many argue that the costs of ethnic studies as a graduation requirement would outweigh the benefits. Komlos believes in the importance of the subject but hesitates to make it a graduation requirement because finding teachers would take effort, time, and money. “I feel like the content should be taught, and should be discussed in some way in our public schools. My fear of making it a graduation requirement is that that content will be diluted — it takes a really special teacher to bring all these elements [together],” she said. The impact of the class is worth the cost of hiring satisfactory teachers and standardizing the curriculum.

In 2018, former Governor of California Jerry Brown vetoed a bill that aimed to make two semesters of ethnic studies necessary for high school graduation. Brown largely justified his decision by noting that an additional graduation requirement might cause the workload of high schoolers to increase to the point of being unmanageable. Brown’s reasoning misses the point. Students at Lowell would not be overloadedwith coursework, as the class assigns little homework and would only be required for for one semester.

The original purpose of the 1968 strikes with the Third World Liberation Front was to fight for underrepresented voices to be integrated into our education system, and it’s time to finish what they started. World History and American Democracy are already SFUSD graduation requirements; it is time to take a crucial step toward further diversifying our education system by making ethnic studies a graduation requirement as well.

Steven L. • Oct 31, 2019 at 3:03 pm

Thank you, Eric and Sarah, for bringing awareness on the subject of Ethnic Studies because ethnic communities and their history in America is not understood or reported by mainstream media, thus the American public does not know their contributions to the economic development of America. Ethnic communities and their American stories are very important to learn in understanding American values, such as freedom of speech, self-reliance (i.e. independence), right-to-privacy and equity for all. Thank you and keep the American Spirit alive.