Why I support legacy admissions

Imagine you’re a parent with $500,000 at your disposal. What would you do with that money? Maybe you would save it, buy a house, invest in the stock market. Or maybe you would bribe officials and coaches at top colleges to buy your kid a spot in the school’s freshman class. That’s what 35 Hollywood celebrities and CEOs did.

College admissions has become extremely competitive, with parents shelling out thousands of dollars for test prep programs and college counselors to give their kid an edge. With the recent Harvard admissions lawsuit and the college bribery scandal, questions have been raised about the ethics of college admissions, and how schools can make more fair decisions. These two events have also brought to light the debate surrounding legacies and whether this policy is in fact an obstacle for making a more diverse, meritocratic student body. While the legacy advantages may seem unfair, a closer look at this policy reveals that, in fact, it’s not just legacies that benefit, but other students and the college as well when it comes to financial aid and resources for the schools.

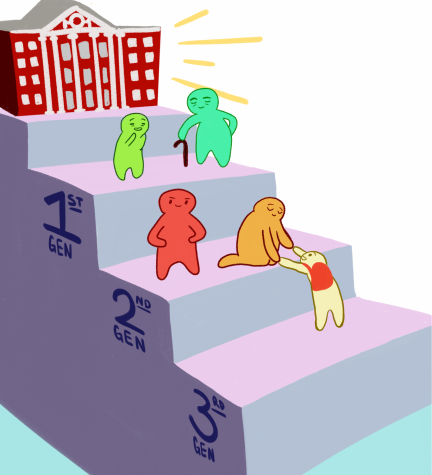

The biggest argument against legacy admissions at elite schools is that they are unfair and promotes generations of institutionalized racism, as most legacy students are white and wealthy. While the demographics of legacy students are mainly white and rich, this demographic is changing drastically. At Harvard, 52.7 percent of its students are minorities, and this seems to be a growing trend amongst many elite institutions. With this brings a new generation of highly educated alumni of color who will be able to pass down their legacy status to their children. Ashton Lattimore, an African-American writer and lawyer who graduated from Harvard wrote in an article by the Washington Post, “The moral rightness of ending legacy preferences to create a more equitable admissions process comes with a bittersweet edge: It adds one more thing to the pile of privileges that people of color can’t pass down to our children as easily as untold generations of whites have done.” With changing demographics, more people of color are now benefitting from the policy, and taking it away would deprive these graduates of a privilege that they worked so hard for.

Another misconception about legacies is that they prevent socioeconomically disadvantaged applicants from having an advantage. While this may be true for a few cases, most students admitted into elite schools are already from privileged backgrounds regardless of whether or not their parents went to that school. For every legacy student who is rejected there is one upper-class student who is accepted. Also, legacies are more likely to donate to schools. Due to the country’s changing social and political climate, many elite colleges want to diversify their campuses. With these donations, schools have more money to do outreach to disadvantaged areas, and provide generous financial aid to low-income students. Without these donations, these schools would not have as much room to help disadvantaged students.

There is a lot of thought about and obsession with who and why certain applicants get into colleges and why others don’t. A common misconception is that legacy students have a much greater chance of being accepted regardless of their grades, test scores, extracurriculars and essays. This is not true. In fact, the pool for legacy students is much more competitive, as these students are more likely to have higher GPAs and scores compared to the non-legacy applicant pool. Legacies still have to reach a high bar to be admitted into schools, especially as many universities’ acceptance rates are below 10 percent.

Having legacy status is just a thumb-on-the-scale component of admissions, meaning if there were two equally qualified applicants but one of them happened to be a legacy, chances are that legacy student would be admitted. Legacy status is only a small component of the application. On every Ivy League’s common data set (public documents which show the importance of the different components of an application), alumni relation is categorized as “Considered,” the third lowest of importance. Jeffrey B. Brenzel, who was Yale’s Dean of Admissions in 2011, said in a New York Times article that they “turn away 80 percent of [their] legacies, and [they] feel it every day.” Brenzel added that Yale also rejected more children of the school’s Sterling donors than they accepted (Sterling donors are the university’s most generous donors; they donate at least $1 million to Yale), proving that sometimes even copious amounts of money cannot guarantee you an acceptance. So, if some of these legacies are being rejected, who is getting these spots? Chances are, it’s another upper-middle or upper-class applicant. Legacy students are not taking away spots from underprivileged students. The fact is is that although many private schools have been doing massive outreach campaigns, most of their student body still comes from socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds. Almost half of the student body at Harvard come from families making more than $200,000 a year. Instead of cherry-picking certain students, we should look at the pitfalls of college admissions as a whole.

There is no secret formula to get into the college of one’s dream. Legacies aren’t guaranteed admission, and applicants who resort to illegal activities are eventually exposed. There are many components that go into the admissions process, and even though the process as a whole has many pitfalls, we shouldn’t blame legacies. Factors such as stress and the obsession with acceptance to elite schools has created a toxic culture of cutthroat competitiveness–a culture that many students and families contribute to regardless of legacy status. If we want to make the process more fair and more diverse, we need to not just continue reaching out to underprivileged students, but also provide more support early on. As college admissions gets ever more competitive, schools must take advantage of the short time they have to give their students as much effective support as possible. Maybe one day, we will see more schools with a larger community of alumni of all backgrounds who will be proud to pass down their legacy status to their children.