Shedding Light on Lowell’s Shadowing Policy

Entering Lowell, you are a little fish in a big pond. The first few months can be brutal academically and socially, and hurtling into freshman year with no idea what to expect can make it so much worse. However, some students do know what’s ahead. A small population of eighth graders are able to shadow Lowell every year with friends and family members, leaving the playing field unequal. We should reimplement a shadowing program to combat this problem.

As of now, shadowing at Lowell sits in a gray area. There is no official way for students to sign up for shadowing, but those who have connections within the school are able to shadow friends or family. This wasn’t always the case; Lowell offered shadowing several years ago, but the administration shut down the program because the demand for it was too high. Now the school only officially offers tours and Eighth Grade Night.

Several other public high schools in San Francisco, including Ruth Asawa SOTA, Abraham Lincoln and George Washington, along with various private schools, allow eighth graders to shadow before they send in their applications every December. This process immerses students in the school’s community, whereas school tours only scratch the surface of the complex high school experience.

Principal Andrew Ishibashi, who made the final decision to discontinue shadowing, was mainly concerned with Lowell’s inability to accommodate all prospective shadows. “Lowell is a very popular school, and we couldn’t accept everybody,” he said. According to Ishibashi’s approximation, Lowell used to receive 3,000 shadowing applications and had to reject at least half. Ishibashi was specifically concerned about refusing minority students. “If the door is closed in your face when you already feel like people don’t care, and like you’re not wanted at a school like Lowell, that’s hurtful,” he said. Ishibashi recalled trying multiple methods to expand the number of shadows Lowell could host, but the influx became a space issue and a distraction. He ultimately decided that shadowing was too much of a strain on the Lowell community.

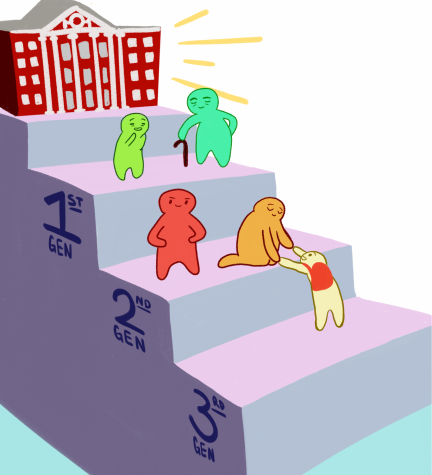

While Ishibashi’s sentiment towards minorities is appreciated, eliminating shadowing has in some ways been harder on minority students. With no policy in place, Lowell students have begun hosting shadows without the administration’s consent. Within this unofficial system, you can only shadow Lowell if you know someone attending the school, often a family member. This requirement of knowing a Lowellite in order to shadow restricts prospective Latinx and African American students, given how these groups combined only comprise 12 percent of our student body, according to the Lowell High School Profile 2017-2018. In addition, shadows of minority races are more recognizable as non-Lowell students because the population of their ethnicity at Lowell is so small. One anonymous sophomore encountered this issue while hosting an African American shadow. “If you see someone who is African American, it’s really easy to recognize that they don’t go to the school,” she said. She was reprimanded for bringing an unauthorized shadow on campus by a security guard who identified her shadow as a non-Lowellite.

As for the distraction factor, the issue could be reduced by simply accepting fewer students, instead of attempting to host as many shadows as possible. That way, shadowing would be less frequent and disruptive. Though some families may be upset about not being able to shadow, letting in some students is better than none.

By developing a concrete policy instead of leaving students to their own devices, the administration could dictate a specific set of rules for shadows’ behavior. Sophomore Mark Verzhbinsky agrees on the benefits of clearer guidelines. Verzhbinsky shadowed his older sister and admitted he probably distracted her classmates, who were interested in meeting their friend’s brother. He believes this problem would be eliminated if students shadowed random volunteers, keeping the process impersonal.

In order to keep the system more equal, shadows could be chosen through a lottery system. That would eliminate the inequity surrounding the way students can shadow now.

Lowellites who have shadowed multiple schools claim that they gained a lot of good insights from shadowing. Freshman Virginia McDonough, who shadowed multiple private schools as an eighth grader, appreciated having the ability to shadow. “It gave me a better view of the classrooms and how I would fit in to the school,” she said. “It showed me whether or not I liked the teaching style or how I would do in the environment.” In a survey conducted by The Lowell in March that aimed to collect student data and opinions about the usefulness of shadowing, other students responded similarly to McDonough. “You learn so much about the people and it helps you determine whether you can picture yourself there or not,” one student said. Another said shadowing “created a more genuine idea of the student experience.”

McDonough wishes she could have shadowed at Lowell, finding the information she gleaned from attending Eighth Grade Night insufficient. Because of her lack of exposure to the school, she felt confused upon entering freshman year. “I didn’t get to know where anything was or experience any of the classes [during Eighth Grade Night]. That was kind of hard,” McDonough said. Verzhbinsky compared shadowing and touring Lowell, outlining the differences between the experiences. “It’s either looking in from the outside through a filter, or actually being on the inside,” he said.

In addition to helping prospective students gauge their compatibility with the community, McDonough believes that a shadowing program at Lowell could help clear up some misconceptions. Lowell is seen as a rigorous academic environment, and allowing eighth graders to shadow could illuminate other aspects besides our competitive nature. “[Shadows] could see what other students are actually like, what the classrooms are like…It’s not just people studying and crying in the bathrooms,” McDonough said.

While many like McDonough find Lowell less intense than expected, for some the opposite is true. Lowell is stressful, and understanding that sometimes requires seeing the workload and classes with one’s own eyes. The aforementioned survey by The Lowell revealed that seeing difficult academics first-hand would have dissuaded some applicants. “Seeing how crowded it is all the time, how classes work compared to other schools…might have made me reconsider,” one student said. “If I [had] shadowed, I probably wouldn’t be at Lowell,” another said.

Though the former shadowing policy was discontinued with good intentions, eliminating a program because not everyone can be accepted is not a reasonable solution. Lowell doesn’t shut down because we can’t accept all ninth grade applicants, so why should we follow such a cut-and-dry policy when it comes to other aspects of our school? Even if we can’t accept everybody, the experiences gained by those who shadow, whether positive or negative, greatly helps them along in the high school admissions process. We shouldn’t rob those students of this golden opportunity.