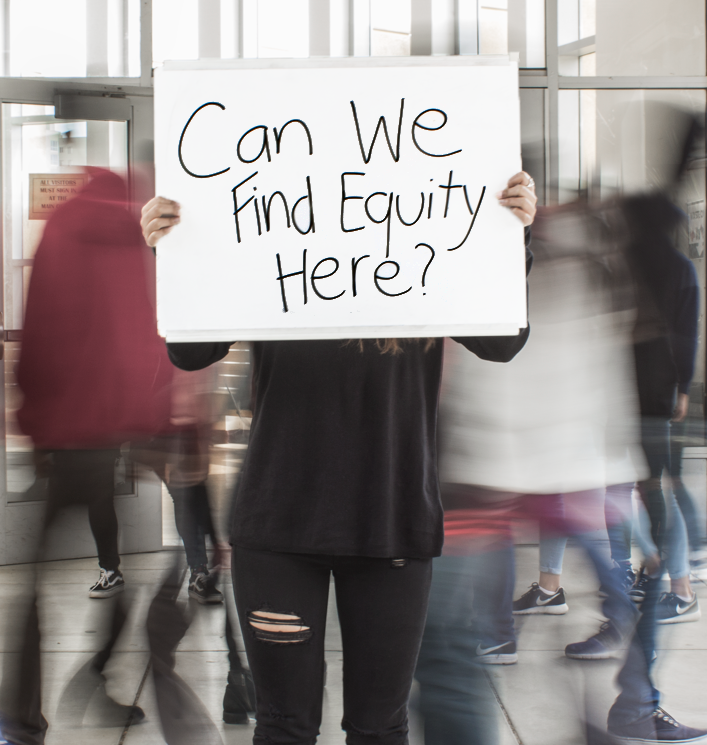

Finding Equity, Part 3: Why we must promote cultural sensitivity and diversity among students

“The only question I have for you all today is this: why did it take this long?”

The inquiry rings out from junior Tsia Nicole, president of Lowell’s Black Student Union (BSU). She’s accusing the administration’s efforts to address the discrimination faced by the school’s African-American students as being long overdue.

The San Francisco Unified School District meeting room is silent after her words. Its inhabitants are anticipatory as they listen to the BSU jump start what will hopefully be a series of reforms.

This moment at the Board of Education meeting on Feb. 23 followed a student walkout and speech at City Hall. These were the culmination of a school year where the insensitivity that minority students experience at Lowell was brought to light, partially through parts one and two this series. The last straw for the students at the walkout was an unpermitted photo display demeaning Black History Month. The administration responded by taking down the display and holding mandatory school assemblies, but many believed the response was insufficient.

The recent events reflect a serious issue in the Lowell community: a lack of understanding of underrepresented minority cultures. In order to create a more welcoming atmosphere for every student, Lowell must take steps towards supporting minority students and educating all students about cultural awareness and sensitivity.

What are the district and Lowell doing?

The school district, working with the Lowell administration, has agreed to meet select demands of the BSU. The school is currently engaging in discussions to build a community center for minorities, require cultural competency training for staff, and hire a recruitment officer to enroll prospective African-American students. Matt Haney, the SFUSD Board of Education president, announced this at Youth Advocacy Day on March 17.

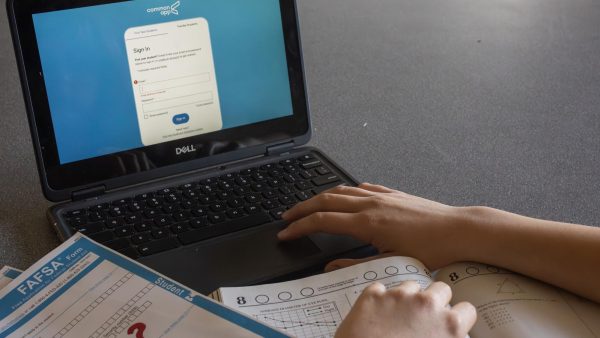

At Lowell, students believe that the administration is not doing enough to fix diversity issues, according to a survey conducted by The Lowell and the Lowell Data Club on Feb. 4, the day before the administration reacted to the offensive Black History Month display.Although 76 percent of students think that the administration should address Lowell’s racial issues, only 28 percent feel that the administration is doing so effectively.

The recent events reflect a serious issue in the Lowell community: a lack of understanding of minority cultures.

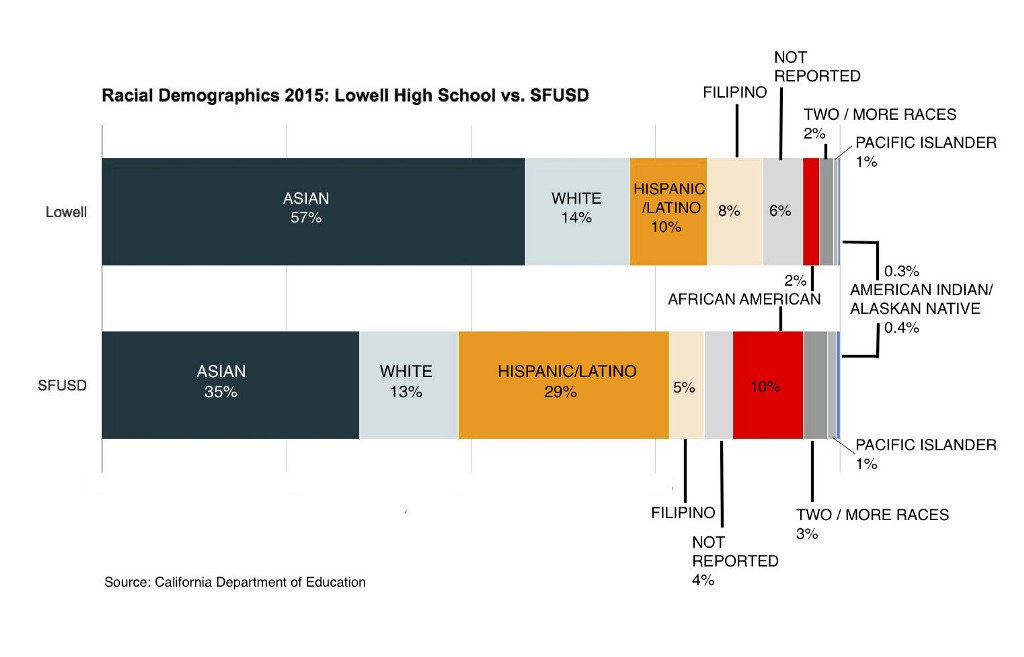

In April, principal Andrew Ishibashi announced new efforts, including a new Alumni of Color Mentor Program, a Cultural Club Council, and diversity in hiring teachers and recruiting students. The latter was a specific BSU demand, considering that since the 1999–2000 school year, the African-American population at Lowell has never exceeded three percent. This year is no different — only 45 Lowell students are African-American.

The Lowell administration has been attempting to address diversity issues. In 2013, they hired special consultant Hoover Liddell as a part of Lowell’s African American Core Education and Support program. This year, Claudia Anderson was hired to play the same role for Latino students.

Professional development for teachers this year included a video on and discussion of systemic oppression in the U.S. and segregation in SFUSD schools. Next year’s professional development will include a similar section, according to Ishibashi.

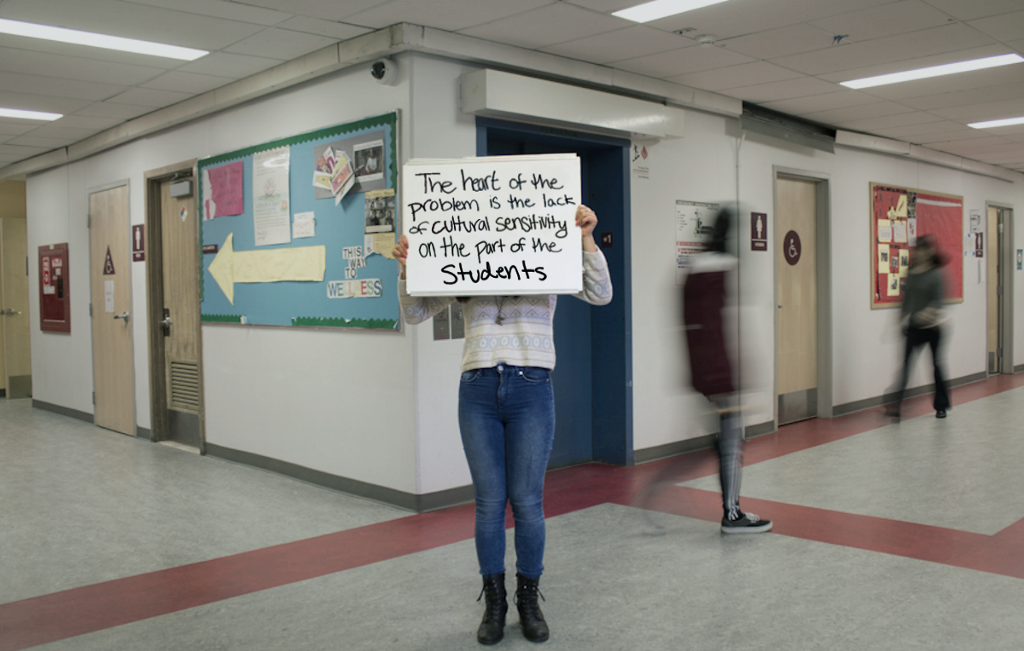

Yet these efforts fail to directly confront the problem behind the events that happened this year — a problem related to why minorities feel unwelcome at Lowell. The heart of the problem is the lack of cultural understanding on the part of the students.

When the Class of 2016 Board decided to print “Most Ratchet” as a category for the Senior Pop Polls, they “were unaware of the negative connotations of the term ‘ratchet,’ or of any racist implications behind the word,” as they said in a Nov. 28 letter to the editor. The student who posted the racist pictures about Black History Month said he “didn’t realize it was something [other students] would get mad at.” In fact, over 30 percent of students see people using racial or ethnic stereotypes about once a day, and over 20 percent see it many times a day, according to our student survey.

While teachers have and will continue to obtain cultural competency training, there has yet to be a similar effort made to require students’ awareness about cultural sensitivity. So how can we expect that similarly insensitive situations won’t occur again, if students are not taught how to be culturally aware?

What happens in the classroom?

Currently, the main way diversity enters the classroom is through the efforts of teachers. The Lowell asked teachers at the school how they diversify their classrooms and curriculum. Most responses included randomized seating and grouping assignments. Many Social Science and English teachers said they incorporated diverse points of view into the curriculum.

Although the World History state standards and textbook are not Eurocentric, according to World History teacher Matthew Bell, he still reinforces his teaching with diverse documents. “If students are just reading the textbook and we don’t introduce other voices and sources, then it can seem very Eurocentric,” Bell said. “I think it’s a matter of how it’s presented and how the students are assessed.”

Forty-six percent of students see segregation by race or ethnicity at Lowell during free blocks.

Bell’s teaching of World War II in his eleventh grade U.S. History class focuses on the Asian theater of war rather than the European — a flexibility he has since state standards for the 20th century curriculum are not specific. He chooses to do so because his Asian students could have families that immigrated during the 1960s and 1970s, and hopes that they can discuss with the experiences with their parents. One student recorded and brought to class an interview with her parents about their decision to leave Vietnam. Armenian students have also told the class personal family histories related to the Armenian genocide. “Those have been some of the best moments teaching here, when students bring their stories,” he said.

Starting next year, Bell wants to begin framing his course using a continuing narrative of identity. The formation of the working class during the Industrial Revolution and the slaves who successfully led the Haitian revolution are just two of many events in history where identities are created by force, domination and oppression. “If we just use identity as a theme throughout and take a historical approach to it, I think that’s a better way to teach it,” Bell said.

Similarly, Advanced Placement English teacher Jennifer Moffitt taught Invisible Man by African-American writer Ralph Ellison, a novel that covers issues of identity, internalized racism and stereotyping. Last year, to prove the relevance and persistence of the issues raised in the book, Moffitt gave her class a passage from the book of a funeral speech, with characters’ names removed, for a black man who was shot by the police. “They thought it was actually a speech that somebody had given at one of the funerals of somebody killed by a cop,” she said, comparing the fictional work from 1952 to the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and other similar occurrences in the recent years.

Moffitt supplements the book with a reading of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a defense of civil disobedience and human rights, and a showing of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, a satire film about the success of a modern minstrel show with black actors in blackface. The experience and issues faced by black men trying to succeed in their respective lives are parallel in all three works.

Although teachers can evidently incorporate diversity into their curriculum, it should not depend on a teacher’s choice alone. According the student survey, 72 percent of students believe that teachers should be addressing racial issues in class. However, only 33 percent of students felt that teachers were doing so effectively. Are not enough teachers choosing to teach a diverse curriculum either due to personal preference or time constraints? Or is it just not effective enough?

What should students be doing?

In response to the incidents of the past year, the Lowell Student Body Council chose Inclusion as this year’s theme for Social Awareness Week from Feb. 22–26. Among the events aimed towards raising awareness about minority cultures and experiences were San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi’s presentation of his new short film Racial Facial, which features images of racism in the US, and the Alumni of Color panel, where alumni told stories about their experiences at Lowell as minorities.

However, attending these events is voluntary. Students should not be able to opt-out of an education that aims to increase cultural awareness. Social Awareness Week was a beneficial opportunity for students to learn about inclusion and culture, as are the Social Change and Critical Thinking elective and the Ethnic Studies elective, but the fact that none are compulsory means that the people who need the education the most are not getting it.

Peer Resource Leaders, who participated in the planning of Social Awareness Week, agree that the largely voluntary participation lessened its potential impact. “The people that were interested in it were the ones who ended up going, as opposed to how the people who aren’t interested in it didn’t take it as seriously,” senior Peer Leader Regina Gomez said.

In the first- and second-year of Social Change and Critical Thinking, taught by Peer Resource coordinator Adee Horn, students learn about oppression and race, and educate their peers by creating workshops.

The third year Social Change and Critical Thinking course, home to Peer Resource Leaders, has taken initiative to support minority students through the Peer Mentoring program and the Stress Free Fair. Taking the advice of BSU, La Raza and other cultural clubs, the 2015–2016 Peer Mentoring leaders assigned a mentor of color to every reg that had a freshman of color to provide a role model for minority students. April 22 marked this year’s Stress Free Fair, and it included presentations on stress caused by institutional racism.

“To avoid [the narrative of white supremacy in Ethnic Studies] would be to miss a complete education.”

Why we need Ethnic Studies

The limits of voluntary participation are true for Ethnic Studies as well, despite the importance of the class. The value of Ethnic Studies, a new year-long elective added this school year, was demonstrated in the Board of Education’s decision in Dec. 2014 to require every SFUSD high school to offer an Ethnic Studies course.

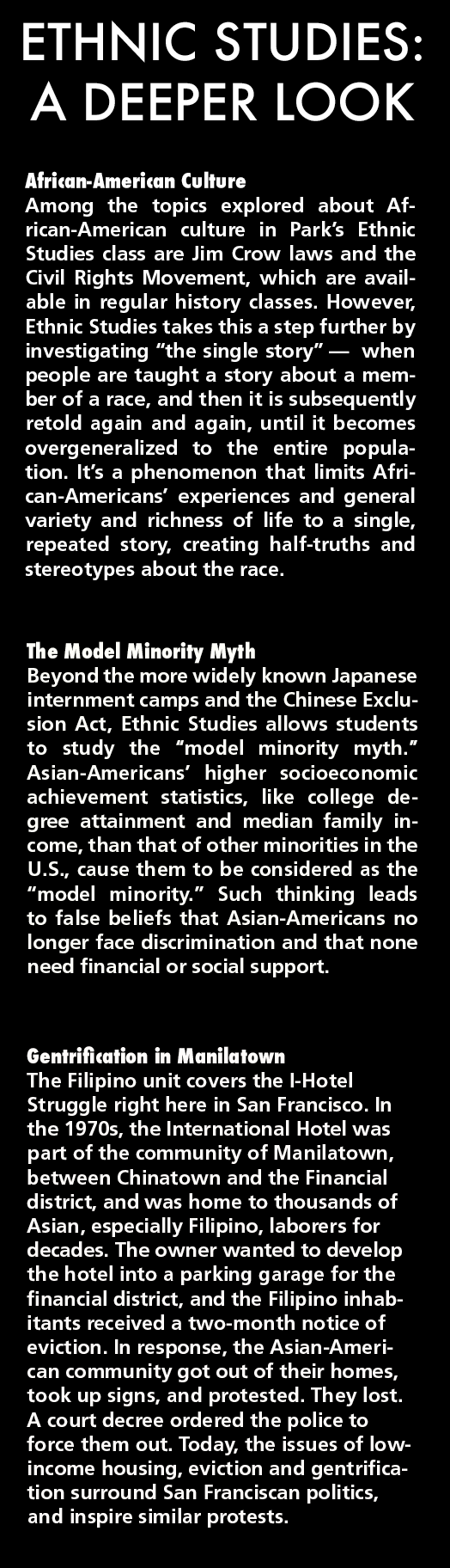

Ethnic Studies’ curriculum covers identity, systems and power, countries’ influence and transformation and change. Ultimately, the course seeks to examine the social construction of race and the resulting marginalization of communities that have historically been critical to the development of the United States, according to Ethnic Studies teacher Soo Park.

The course is also invaluable because it retells history from the points of view of African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, Filipinos and Native American — perspectives that can be absent from other history classes without teachers’ choices to use supplemental material.

Ethnic Studies takes a different disciplinary approach and is a different side of history, according to Bell. He cites Ethnic Studies’ focus on critical race theory, sociology, structures of power and the psychology of identity as material that distinguishes it from World History. However, Bell supports Ethnic Studies as a separate elective course, but not as a mandatory course. “One thing I do know about Ethnic Studies is that it employs a narrative of white supremacy and I think that is a great narrative to explore,” he said. “To avoid it would be to miss a complete education.”

“To avoid [the narrative of white supremacy in Ethnic studies] would be to miss a complete education.”

Ethnic Studies can also help minority students feel more comfortable at Lowell and inspire empathy among non-minority students. “I think that starts with empowering our students of color and by educating our community about what it feels like to be marginalized, to be empathetic,” Community Health Outreach Worker Xavier Salazar said.

Courses like Ethnic Studies can increase non-minority students’ willingness to act to promote diversity, according to a 2011 study published in the Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology journal.

Ethnic Studies is already an essential part of the curriculum at the Urban School of San Francisco, a private high school with a white majority. Required for all students, the course completely changed the perspective of junior Casey Leffers, who had always studied at schools where the majority of the population was white like he is. “Beforehand, even the idea of racism wasn’t the reality to me,” he said. His understanding and education on race and racism had been limited to simply learning about Martin Luther King Jr. in sixth grade. “I just couldn’t grasp the concept of someone murdering someone else because of what they look like,” Leffer said.

After taking Ethnic Studies, Leffer’s point-of-view on race, racism and oppression expanded. “It’s definitely made me look at things differently, especially when I’m thinking about whether events are racially motivated or not,” he said.

Leffers said that if Ethnic Studies had not been a requirement at his school, he would not have known — or wanted — to take the class.

When Ethnic Studies is offered as an elective as it is at Lowell, some non-minority students hesitate to take Ethnic Studies because of its reputation as a course that is unwelcoming to non-minority students. Freshman Isabella Dang, who takes Ethnic Studies, has white friends who asked her what the class teaches. “A few of them said that they were warned not to take this class because they’d feel discriminated against,” Dang said. “But Ethnic Studies isn’t a class where we [throw] shade on a race, it’s a class to learn about diversity and solidarity.”

That learning extends even to minorities, especially for those who say they grew up in a bubble. San Francisco State University junior William Juarez, who studies at the only College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S., was raised in Los Angeles, where he saw only other Latinos, African-Americans and Koreans and did not personally experience racism. His studies in school reinforced his belief that racism did not exist: from elementary school to high school, he was taught that slavery was a benign institution and that slaves were paid. He was therefore reluctant to take Ethnic Studies. “I remember telling my roommate, a Latino Studies alumna, that I didn’t like the courses because I felt that racism was behind us now,” he said.

The readings he did in Ethnic Studies changed his view completely. Especially impactful for Juarez was the poems of Gloria Anzaldua, a lesbian and Chicano scholar, whose work showed Juarez that he belonged in the Latino community despite being gay. “Ethnic Studies is critical because the curriculum provides the coursework and research to understand all our collective histories, better understand our present, and the possible implications for our future,” he said.

Lowell freshman Kaitlyn Evangelista initially was reluctant to take Ethnic studies because it is an elective, but she quickly saw the value of the class. The course connects concepts such as systems of power and oppression to relevant current events like the water contamination crisis in the poor and minority communities of Flint, Michigan, as an example of environmental racism. “We talked about what people are experiencing and how the government tried to cover it up, the way power can manipulate, and what the media hasn’t covered about the damaged water,” she said.

Leffers said that if Ethnic Studies had not been a requirement at his school, he would not have known — or wanted — to take the class.

The course also taught Evangelista the importance of being able to understand other people’s points of view. When watching the film Korla, which explores the life of a black man from Louisiana who passed as an Indian musician in the 1950s, Evangelista was first confused as to why the protagonist was denying his identity as a black man, but soon realized why. “In this period of time, a black man would experience discrimination, racism, and microaggressions,” she said. “Posing as an Indian man would allow him to live a better life.”

With its ability to educate both non-minorities and minorities and help students come to terms with their own and others’ identities, Ethnic Studies is undoubtedly a valuable class. Therefore, Ethnic Studies must be mandatory.

Some members of the SFUSD Board of Education are already looking into this possibility. The resolution passed in December 2014 that established Ethnic Studies at every SFUSD high school, including Lowell, states that in the 2020–2021 school year, legislators will determine if Ethnic Studies should be implemented as a graduation requirement.

Although concerns were raised that a mandatory Ethnic Studies class could inhibit students from taking as many AP courses as they do now, the benefits of Ethnic Studies outweigh the costs. “We live in a world with lots of different people in it, and we need to learn to get along with them,” counselor David Beauvais said. “And APs are fine if you can take it, but if not, you can take it in college.”

Nicole put it the best when she said, “The problem at Lowell is that people care more about taking APs, which really aren’t mandatory or necessary at all, rather than trying to learn about other people’s culture so that other people can feel welcome in an environment where they don’t.”

Some people, like Ishibashi, recognize the benefit of having all students learn Ethnic Studies, but believe that the material should instead be incorporated into existing classes — much like the Plan Ahead activities for freshmen is an incorporation of the College and Career course into freshmen classes.

However, doing so is unfair to Ethnic Studies. Incorporation will allow other material to overshadow Ethnic Studies material. “The problem with incorporating Ethnic Studies into history classes is that it won’t be focused on Ethnic Studies,” Nicole said. “It’ll be more focused on other things and it’ll stray away.”

Why we need panels

However, classroom instruction alone is not enough. Relating discrimination to the daily Lowell experience was done particularly well, recently, on two fronts.

“The problem at Lowell is that people care more about taking APs, rather than trying to learn about other people’s culture so that other people can feel welcome in an environment where they don’t.”

The first was when the BSU shared their experiences at City Hall and the Board of Education meeting, which led to student revelations that discrimination does occur at Lowell. It can be difficult to connect a concept or a distant event with daily life, according to Gomez. Gomez was therefore shocked by the discrimination at Lowell faced by her friend, senior Maya Bonner, who recounted her negative experiences at City Hall after the BSU walkout. “Her adversities really opened my eyes, even though as a Peer Leader, I’ve learned about cultural appropriation and such everyday,” Gomez said. “It was surreal.”

The second was when Lowell alumni brought their stories to the Alumni of Color panel during Social Awareness Week. One alum described how as a student she had been asked by her teacher if her black friends sold her drugs. Another alum reflected on the segregated seating in the cafeteria. Not only did the panel empower students who are going through the same experiences, but it also “educated other students about the way it feels like being on this campus and not seeing many people like you, even though you came from a middle school or a neighborhood where it is all people like you,” according to Salazar.

A joint panel, consisting of both alumni and students of color, would provide a personal view of discrimination at Lowell and bring words like “racism” to ground level for non-minority students. An annual event would help the community understand more intimately what minorities’ experiences at Lowell are really like.

A recent recruitment event for Latino students demonstrated the effectiveness of a joint panel. The panel, consisting of students, alumni, counselors and current parents, was successful, according to Anderson. The honesty present in the panel encouraged parents to be equally candid, asking questions like “Is my child going to feel included here?”

Understanding the reality of others’ experiences could decrease self-segregation at Lowell, allowing all students to feel more included. As it stands now, self-segregation is a real issue. According to our student survey about diversity, 46 percent of students see segregation by race or ethnicity at Lowell during free blocks and 43 percent when students choose their own seats and groups in class — both situations that occur when students are given choice on whom their companions are.

With the addition of Ethnic Studies and an annual panel of minority students and alumni, students of all races will better understand the experiences of minorities, thereby increasing inclusion.

Moving closer to equity

These attempts would only be the first of many steps that Lowell needs to be take to address racial issues. However, the truth of the matter is that racism exists beyond Lowell, San Francisco, and even America, and if we do not attempt to amend our faults now, then we enter a cycle of bigotry. For example, not receiving an education on Ethnic Studies causes a lack of awareness in our youth, whose interactions with others are flavored with microaggressions, and who then grow up to be the leaders of our society and perpetuate the original lack of awareness.

But what is crucial and commendable is that Lowell is playing its part to support its minority students, both by giving them direct support and by increasing the sensitivity of non-minority students. Recognizing that a problem exists is the first step to making amends — and moving closer to finding true equity.

Ophir Cohen-Simayof, Whitney C. Lim and Rachael Schmidt contributed to this article.

This story is part three of The Lowell‘s “Finding Equity” series. Part one looked into the African-American experience at school, and part two shared Latino students’ stories of their problems with Lowell’s lack of diversity.

May 19 at 11:30 p.m. correction: An incorrect opinion attributed to social studies teacher Matthew Bell was removed. He supports Ethnic Studies as a separate elective course, not as a separate course. The Lowell apologizes for the mistake.

May 20 at 2:12 p.m. correction: A previous version of this story referred to “freshman World History state standards.” For clarification, the World History course is generally a tenth grade course, but ninth grade at Lowell. Bell’s use of family stories was in his eleventh grade U.S. History class, not in his ninth grade World History class. Bell’s curriculum theme of identity was not used this year; it is intended for next year.

Originally published on May 18, 2016