It’s not all black or white: reporter struggles with mixed-race identity

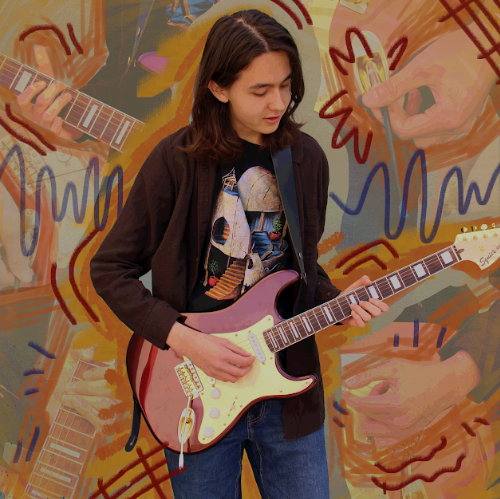

Reporter Rachael Schmidt is half white and half black.

Originally published on November 24, 2015

I arrived at my cousin Angela’s fourteenth birthday party and was the first one there. Her mom is from Malaysia and her dad is German. I immediately gravitated towards her and for the rest of the evening, we exchanged gossip, played guitars and harmonized together.

Once my father’s side of the family began to arrive and attempted to interact with us, we retreated to her room. My cousin and I always laugh when we joke and scream, “Run away!” as we make our great escape. But I have always wondered why we feel so inclined to leave when our other relatives, who are mostly white, begin to show up.

I used to figure it was because of our vast age differences in comparison to our other family members’, but the more I thought about it after the party, the more I realized that I had grown uncomfortable with my father’s family when I was nine years old and my parents divorced. After my mother, who is black, became absent from family gatherings, I felt even more out of place. I am half white and half black. When one side of my background is taken away, I do not feel complete.

I am half white and half black. When one side of my background is taken away, I do not feel complete.

Before the divorce, I thought I was just white. For a year after the divorce, I thought I was just black. Now I do not know what to think and I have felt this way since I was 10. Because my school and home lives do not have equal representation of my two races, I have experienced immense racial identity struggles that have ultimately led me to feel most comfortable around racially mixed people like myself.

I was born to a family with parents of different races. My mother is black — she does not refer to herself as African-American ethnically, nor does she care which title is used to describe her — and my father is white — he claims he has German, Irish and even French-Canadian ethnic roots. Growing up, I visited my mother’s primarily black side of the family in Texas on occasion, but for the most part, my family life consisted of living with my father’s European side here in San Francisco.

Before the divorce, I thought I was just white. For a year after the divorce, I thought I was just black. Now I do not know what to think.

Deciphering my racial identity was not such a large issue when I was younger. I stuck to what I was most familiar and comfortable with — having racial representation from both sides with me at all times. Family gatherings with my father’s white family were manageable when my mother was there to balance the racial aspect of the group. Likewise, I saw family gatherings with my mother’s side of my family as normal when someone white joined the mix, such as a friendly neighbor. The first Easter I spent with only my father’s side of the family felt so awkward and uncomfortably strange that I have vowed since then to stay with my mother during holiday gatherings. Even with my mother’s company, I wish for the days of my past when my family could congregate normally and the racial components of myself, both black and white, were present simultaneously.

This sentiment remained even after my parents’ divorce, when my mom took 100 percent responsibility for my custody. I was nine years old then. I initially expected to never see my father’s side of the family again when I was caught between the parental split, but despite my father’s regular absence, I actually started to see my father’s side at family gatherings more than I had before.

After the divorce, however, my mom no longer attended my white side’s family gatherings anymore. Without her, the disconnect between my purely white family and me was so strong at these events that I tended to cling to my younger cousin, who is Malaysian and German, since she is racially mixed like myself. We hid ourselves away from the adults and relied on each other’s company to persevere through the day. Without the other side of our races, we felt that parts of us were missing, and that there was an imbalance that just could not be ignored.

Without the other side of our races, we felt that parts of us were missing, and that there was an imbalance that just could not be ignored.

Despite these early discomforts, the question of whether I felt truly black or truly white did not come up until I was eleven. My mother asked how I saw myself, and that was when I told her that I considered myself a “white girl.” She was shocked and insisted that because she was black and because she was my mother, I must consider myself black as well. It was a law of nature, in her opinion. She explained to me that a child with any amount of African-American heritage, whether it was one-half, or one-sixteenth, was considered black in the south, where she is from.

It is the principle she grew up with as a child herself and the one she follows today. My mother is Cajun, which has French and African-American origins, yet she is from Texas. But, because of the all-black rationale instilled in her when she was a child, she forgets her French side and claims she is purely black. Although readily forgetting one race is not as easy for me as it was for her, she has put me down as just black on my transcripts for school as a result.

The problem was that I had never felt just one side of my race. I had black cultural aspects to my mannerisms and I had white ones as well. When I tried to pretend that I was a member of just one race and not the other, it felt all wrong. This was the case at school especially.

The problem was that I had never felt just one side of my race.

Freshman year, I met a friend at school who was black and white like me and I felt especially close to them from the first time we met. We went together to the Black Student Union meeting because, even though we are not just black, we are both listed as just black on our transcripts. During the meeting, we agreed we had never felt more out of place — nearly everyone in the room was fully black, but we were racially mixed. Maybe my friend felt strange because we were two awkward freshmen feeling out of place in our new school, but I had the vaguest sense that my discomfort was for racial reasons. There was some barrier preventing me from feeling at home that I was not aware of at the time. I was white too, and even though it wasn’t listed on my transcript, it mattered somehow. I simply felt as though I didn’t belong. I was too shy to ever bring forth my apprehensiveness to the people running the BSU. My lack of connection with the black aspect of my ethnicity was a problem rooted in my childhood; the BSU could do nothing about it.

That year 2.3 percent of Lowell student identified as belonging to “two or more” racial groups. I wonder now, were they still listed as just one race like I was? Not only that, but nationally, the mixed race demographic is steadily growing. The US Census from 2010 shows that the multiple-race population was about 9 million. The overall number from 2000 to 2010 increased by 32 percent. Are other mixed kids like me feeling inclined to choose one side of their heritage over another?

Are other mixed kids, like me feeling inclined to choose one side of their heritage over another?

I felt similarly off-kilter when I visited my mother’s only black family in Texas during the summer two years ago. Like the BSU, my mother’s family was very kind and welcoming and tried to make sure that I felt at home, but my feelings of discomfort from not being equally represented were deep-settled and embedded from when I was a child.

I realized that summer that the internal struggle I had been battling for so long was a search for a balance in my life. But I could not — and still cannot — find a solution. How can I connect with people who want me to feel like I am just black or just white when I am not just one but rather two?

The reason why I feel closer to people who are racially mixed is that they vicariously provide the balance I look for in my family and school life. Sometimes, I wonder if they are going through identity crises similar to mine, and that thought comforts me somehow, even though I hope that the feeling of being torn between two races will not become a commonality.