Emma, a junior under a pseudonym, dashes through the hallway to get to her next class. Approaching the classroom, she hears a group of boys trailing behind her, including a previous romantic partner. “She’s a slut,” one of the boys whispers under his breath. Emma’s heart immediately drops, tears well in her eyes. As the herd of snickering boys parade past her, the scarlet letter that was stamped on her back left her with a burning sensation of disbelief and alienation for the rest of the week.

At Lowell, incidents of people, especially women, being shamed for their perceived sexual activity aren’t isolated to students like Emma.

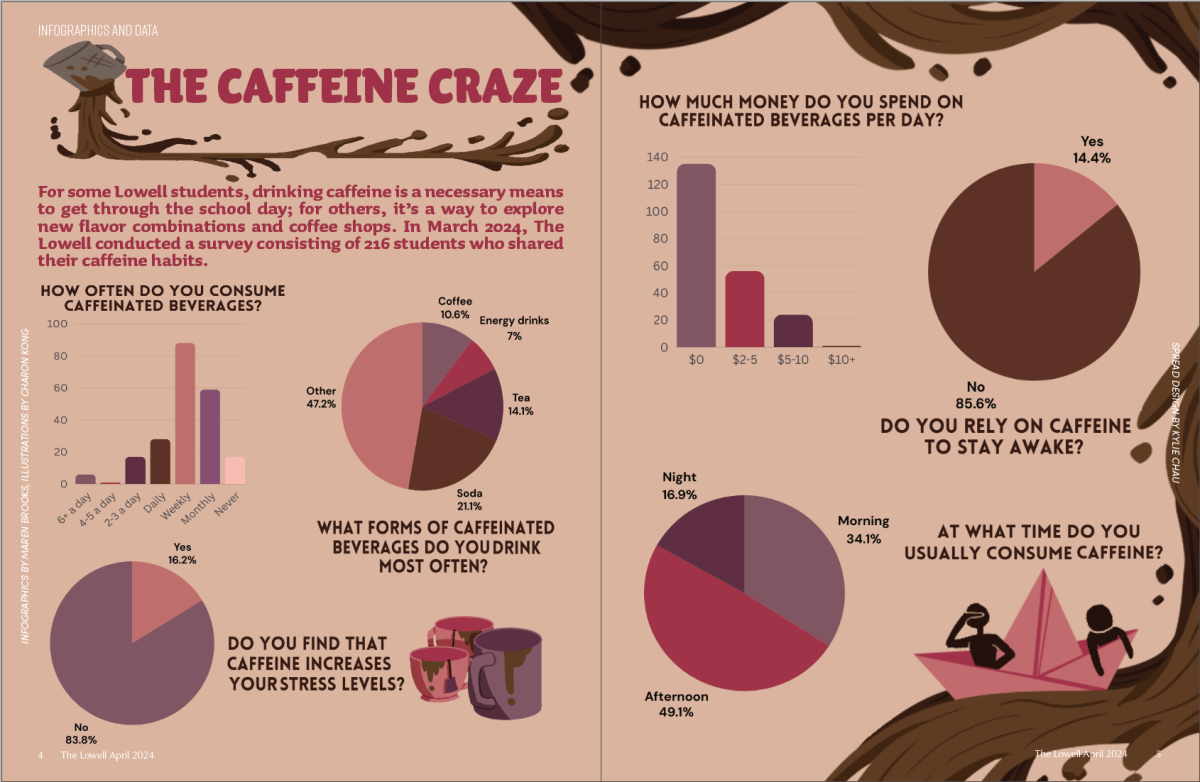

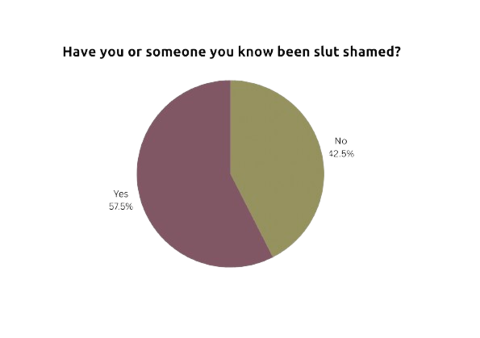

Slut shaming is defined as the harassment of another person for their physical appearance or sexual history being inappropriately provocative. As Lowell has garnered a reputation for excelling in academics and subverting from the normative high school social setting, many students may find their peers being slut shamed an oddity. However, a March 2024 survey conducted by The Lowell of 20 randomly selected registries revealed that 57.5 percent of students have experienced or know someone who has experienced being slut shamed. Students such as Emma have been subject to its subsequent harms, from victim blaming to sexual double standards. The problem is only being exacerbated by evolving online slang, increasing social media usage, and the stigmatization of victims who speak out. Despite Lowell’s Wellness Center making attempts to ensure students’ comfort and safety, the issue remains prevalent.

The etymology of the term “slut” runs deep into the veins of history and societal standards. According to Leora Tanenbaum, a feminist researcher and author of I Am Not a Slut: Slut-Shaming in the Age of the Internet, it was first coined as the term “sluttish” during the late fourteenth century and was used to describe a man that is dirty. “Then the word shifted at around 1450. It became a noun,” Tanenbaum said in an interview with The Lowell. “The gender association also changed, as it became a synonym for a woman of loose character and somebody who was too sexually forward and inappropriately sexual.” Since the beginning of the usage of the term “slut,” Tanenbaum explains that people have shamed others’ sexual freedom as a way of policing their agency. Perpetrators of this form of harassment often believe in the “concept or mindset that if you’re a slut or a hoe, you have done something on purpose, that is wrong,” said Tanenbaum. It follows the idea that having intentionality behind committing a sexual act implies “that people shouldn’t have empathy for them because they deserve it.”

The gender discrepancy in how people are treated for their sexual activity is troubling for some students. Tanenbaum notes that “boys and men are expected to be sexually active even in an uncontrolled manner because that’s what it means to be masculine, but when girls and women behave exactly the same way, they are punished and judged harshly.” For Emma, this double standard has allowed for her actions to be shamed but not the other party involved, the male counterpart. “It makes me upset because I know that he doesn’t get the exact same treatment that I do,” she said. She believes that although she may engage in sexual activity with another person, the only person who is described as “disgusting” is her, contrary to the guy who is praised as a “player.” This occurs because “women are not supposed to behave that way according to society’s presuppositions about our femininity, that girls and women are supposed to be minimally sexual,” Tanenbaum said.

Senior Patrick Smith has observed this double standard within his own experiences. “Slut shaming is definitely more negative towards women,” he said, recounting stories he had heard both online and from the women in his life. “For men, having more sexual experience is seen as more of a flex, while it is something women are often shamed for,” Smith said. Emma agreed with this perspective, noting that if two students are both sexually active, “the girl will be seen as a slut, and the guy will be seen as cool.”

Targets of slut shaming or sexual assault often experience victim blaming, a distorted attribution of an event used to fault a victim instead of the perpetrator. Tanenbaum describes it as a trauma response that many victims use to cope. “It convinces girls and women who have been victimized that they are the ones who have done something wrong,” Tanenbaum writes in I Am Not a Slut. Senior Caterina Juvara experienced victim blaming when friends of a student who assaulted her began falsely accusing her of being the instigator. “The person who traumatized me was praised, and his friends went around, and slut shamed me behind my back,” Juvara said. This took a toll on Juvara’s mental health, as she began to experience feelings of self-doubt and isolation. “They thought that I was a trashy person for an experience that was not even consensual,” she said. “It was really hard for me to deal with because I felt so much guilt.”

Senior Scarlett Carew suffered similar detriments to her mental health after hearing false accusations about her perceived sexual behavior. When hanging out with a former boyfriend and his friends, one of them told the group, “The only thing that’s been passed around more than a blunt is Scarlett.” As she looked around to see that every person in the circle, including her boyfriend, was laughing at the joke, Carew was filled with both humiliation and guilt. “It really made me feel like nothing,” she said. “I played it off because I didn’t want to make it seem like it was bothering me.” When she confronted her boyfriend at the time, he expressed that calling his friend out for what he viewed as a hilarious joke was unnecessary. “But at the end of the day, it’s not just a joke,” Carew said. “That shit hurts. I went home feeling like shit about myself for a while because I thought it was completely fine that the person I was in a relationship with dismissed me.” Despite feeling devalued by her partner, Carew lingered in this cycle of belittlement for several more months, believing that she was to blame for what was said about her — another method of victim blaming that prompted her declining mental state.

Having faced a prevailing culture of women being hypersexualized, Carew and Juvara have, in turn, been wary of their clothing choices. Juvara grew up learning that women should self-regulate how they present themselves to mitigate their chances of being objectified. “I was raised with the concept that crop tops are ‘asking for it,’ so every time I would wear a crop top, I would internalize that,” she said. Over time, Juvara’s self-esteem and confidence dwindled as a result of receiving constant judgment. “I began blaming myself for the way I dressed, even if there was nothing showing, just because I didn’t have a flat chest,” Juvara said. Echoing the sentiment, Carew is careful to not wear revealing clothes in school to prevent being slut shamed. “I know that if I wear a low-cut top, I am going to be catcalled, and in class, people are going to look down,” she said. “I don’t wear short shorts to school, and I will rarely wear skirts.”

Although slut shaming is almost always targeted at women, non-binary, or queer individuals, heterosexual men are not immune to these incidents. Senior Diego Miller, who has experienced students at school calling him a “slut” and “whore,” describes the transmission of these rumors as misconstrued. Miller believes slut shaming happens to both men and women, but men are typically off the hook when they are the perpetrator. “I think it goes pretty both ways now, but I think it’s still definitely heavier on the girl’s side, so there’s definitely misogyny there,” he said. “Boys get a lot more slack for it than girls do.” Still, Miller was hurt by the messages that were passed around. “As a dude, I feel like people will expect you to accept it, but it still definitely affects you. It’s not something you can really accept with pride,” he said. “You kind of just feel dirty after hearing everything.”

Nowadays, the increased use of social media has only broadened the landscape for slut shaming. Tanenbaum, who began her research in the 1990’s, prior to the ascension of social media apps, notes how the amount of slut shaming that people endure now “has absolutely gotten worse.” Due to social media ensuring that almost every person has a digital footprint, “there’s just no physical escape. You cannot escape a reputation,” Tanenbaum said. Additionally, the ability to anonymously harass others online has given rise to social media users partaking in anti-social behavior such as slut shaming. “It’s so much easier now for bullies and harassers to be anonymous,” she said. “It was hard before social media; now it’s so easy, and it brings out the worst in people.” Carew, who has a social media presence, has witnessed the prevalence of slut shaming through the screen. “You can see [photos] being sent around, people screenshotting it, and so many things ending up in group chats,” she said.

Additionally, the modern slang of teenagers has expanded the slut shaming lexicon. According to the same survey conducted by The Lowell, 96 percent of students have seen, heard, or said the words “slut,” “whore,” “bop,” “ran through,” “thot,” or “hoe,” with over half of them encountering these terms more than once a week. Tanenbaum believes there has been a rise of demeaning vernacular against women. “There are all these other synonyms that we use today. One that is notable is the word ‘hoe,’ which is an alteration of the word ‘whore,’” Tanenbaum said. “The word ‘hoe’ only really crept into our language quite recently, which came up in the 1960s.” The phrase “body count,” a measurement of the number of people that someone has had sex with, has also been widely perpetuated through social media. Smith has noticed the frequency of the phrase being used when speaking about women. “Among the guys I know, the term body count comes up a lot when talking about if we want to date a woman or not,” he said.

Many victims of slut shaming choose not to speak out about their experience, fearing that their reputation may be tarnished. Sophomore Audrey Brogno believes that people who slut shame others threaten their victim into keeping quiet. “They’ll be like, ‘If you go and tell someone something, I’ll tell everyone you’re a slut and that you did this,’” she said. “And everyone always believes the guy because the guy is seen as in power.” Insinuating that the public will trust a guy’s word as the truth, Brogno feels that it is difficult for girls to confide in others without being called a liar. She also finds that girls will be portrayed as “sensitive,” so anything a victim speaks out about would not be considered “a big deal.” For Emma, speaking out as being a victim means being labeled a “snitch,” a term that denounces a person’s morality. People who’ve been harassed would rather conceal their truth than be painted out as a “messy” person, according to Emma.

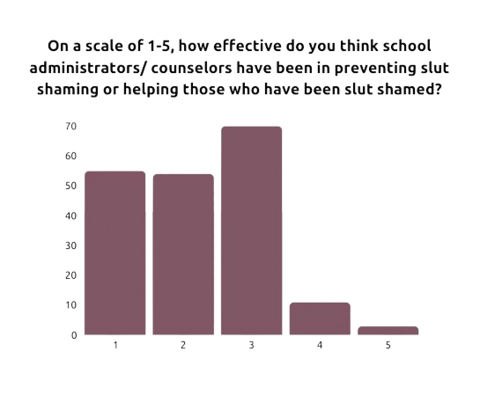

Students such as Juvara and Brogno believe Lowell is not doing enough to address this issue. In the same survey conducted by The Lowell, 56.5 percent of students believe that school administrators and counselors have been ineffective in preventing or helping those who have been slut shamed. When Juvara went to the Wellness Center to vent about traumatic experiences and recurring nightmares, she made future plans for regular therapy sessions, only to be canceled on. “They canceled on me saying to sit tight, saying that they would reschedule a meeting and they never did,” she said. “So I felt really unsupported by that experience.” Similarly, Brogno believes that Lowell administrators and counselors don’t consider verbal harassment as tantamount to physical bullying. “Some students can tell administrators what another student said about them, but they can look the other way and act like that didn’t happen,” she said. “So I don’t think slut shaming is a really big thing on their radar because they don’t really care.”

While students feel that counseling support has been inadequate, Lowell Wellness’ Therapist Kim Banford assures that the program has made efforts to uphold student safety and comfort. Banford’s role is to emotionally support ongoing therapy clients and students visiting the Wellness Center who want to speak with someone. In the event of someone being bullied for their sexual identity or activity, Lowell therapists’ “general protocol is to first and foremost assess for physical and emotional safety, then validate the nuanced feelings about how folks feel that their sexuality is being judged,” Banford said. The Wellness Center has also attempted to take preventative measures by partnering with Lowell’s Students Against Sexual Assault and Harassment (SASHA) club during Sexual Health Awareness Week to promote healthy relationships. In response to students opposing their inaction, Banford states that Wellness is open to conversation and feedback from students on improving their ability to support them. “I’d be interested in further conversations on what feels helpful from students,” she said. “I think that folks deserve to feel supported in a big way and I think that probably takes a multidisciplinary team.”

As students walk down the hallways, the last thing they anticipate is to be called a “slut.” For Emma, the lack of productive conversation surrounding students being slut shamed has only made her increasingly disheartened. “It is so normalized to a point where I don’t really care about it that much,” she said. “I just let time do its thing and move on, so a rumor about me will be in the past and there will be a new rumor about someone else.” Others, like Carew, believe that instead of glossing over the issue as a normalized subject, students should voice their experiences to destigmatize the topic.“If you slept with a lot of people or kissed a lot of people, it doesn’t make you less of a person, and I wish people would stop using ‘slut’ in a derogatory sense,” Carew said. “It is truly okay to seek out therapy or confide in a friend.”