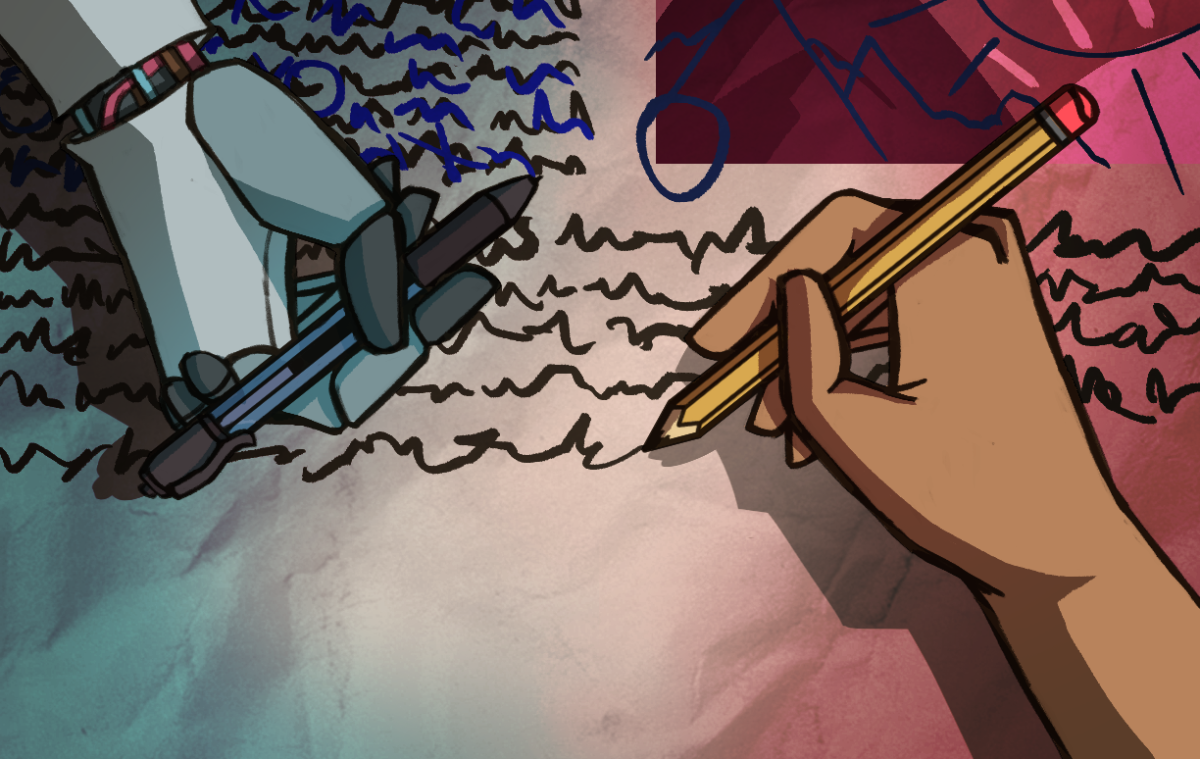

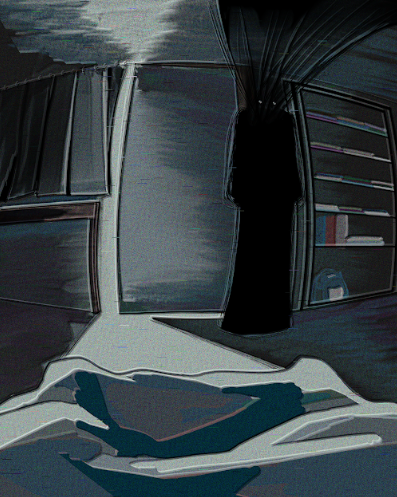

As I face my reflection in the bathroom mirror, the unveiled imperfections of acne fill me with discomfort, triggering an incessant urge to pick at my skin. Picking pimples and scabs, all that remains are trails of blemished surfaces and blood-stained fingers.

I want to erase every pimple, I thought to myself.

The more I picked, the worse my acne became, festering into deep scars. My fixation on “improving” my skin eventually spread beyond my face, as acne afflicted my chest, shoulders, and back, intensifying my self-consciousness. This torment persisted, driving me to seek fleeting comfort by isolating myself in the bathroom for long periods.

I’ve been dealing with acne since I was ten years old, and controlling it has proved challenging. Its severity fluctuates depending on several factors — hormonal changes such as menstrual cycles, stress, and sleep patterns, or dietary choices. Despite changing my diet and using prescribed treatments, home remedies or over-the-counter products, my struggle with acne has persisted.

When acne spots first appeared on my face, I didn’t think much of them, believing they were just temporary blemishes. Nor did I believe that there was anything inherently wrong or unattractive about the pimples on my skin.

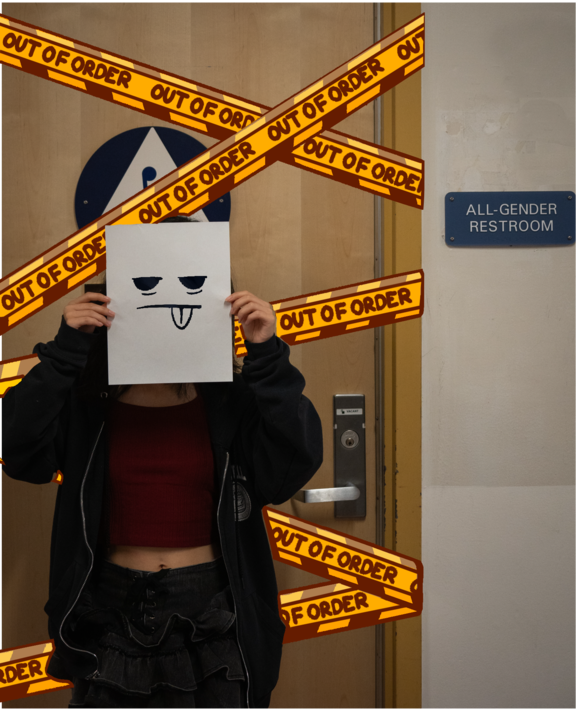

However, it wasn’t long before my classmates began noticing my acne. Hearing my teacher say the word “acne” for the first time in puberty lessons, I recall how the class atmosphere suddenly froze, and all eyes immediately shifted away from the board to me. The weight of every gaze highlighted my imperfections; I felt suffocated by the overwhelming discomfort of my own skin.

Although fleeting remarks about my appearance may not have been ill-intentioned, they instilled a lasting notion that my acne was repulsive and shameful. At times, I even received comments from parents or friends about my skin being unhygienic and undesirable. Little by little, I began to internalize these harmful words into feelings of unworthiness.

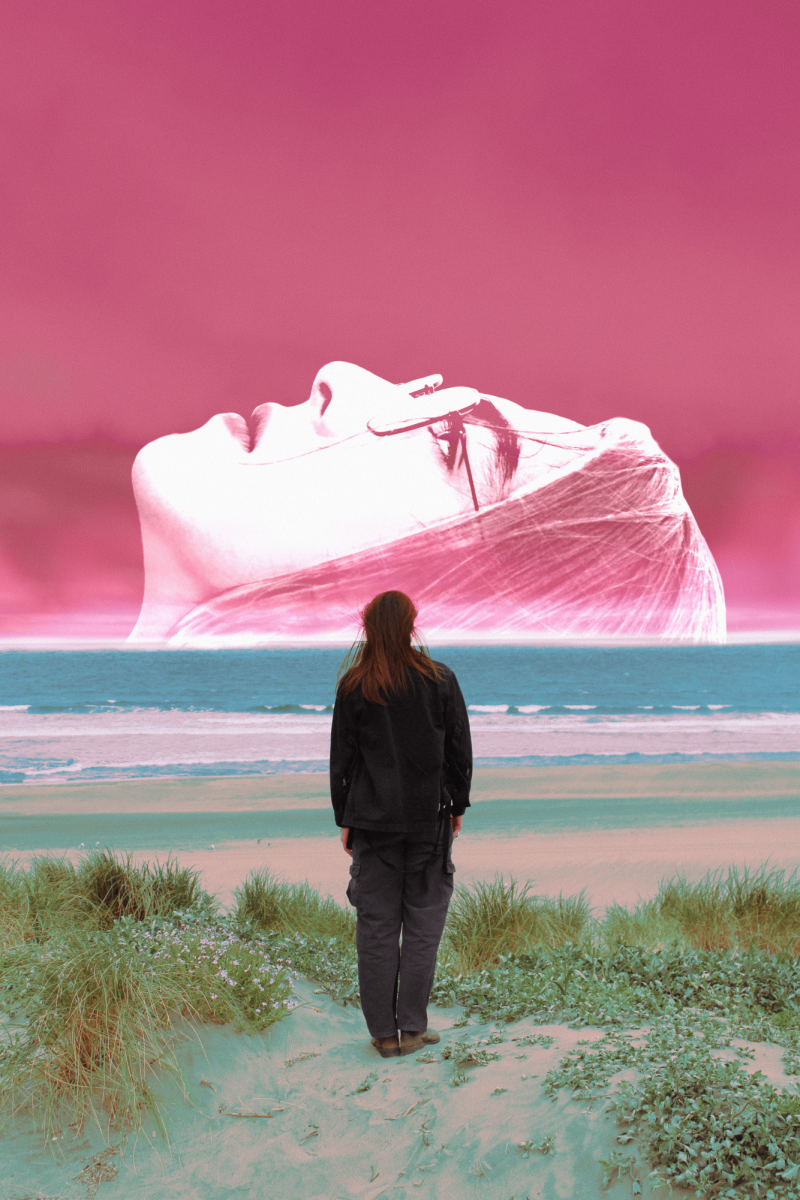

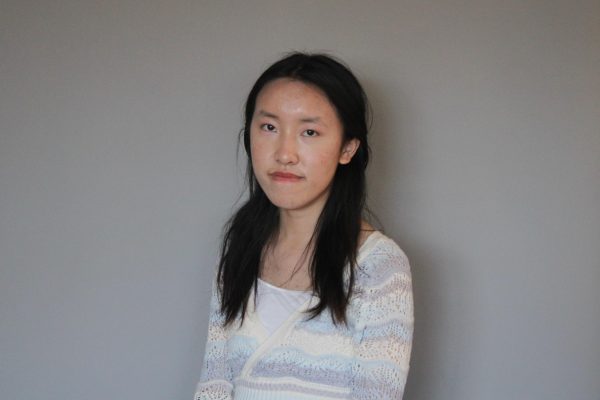

My blemished skin overshadowed how I perceived myself, turning each of my accomplishments or abilities into an extreme self-consciousness. The mere thought of being in the spotlight filled me with anxiety and embarrassment because I was convinced that my face was unattractive. This insecurity held me back from fully expressing myself and actively participating in class, fearing that my acne would be the focal point if I drew attention to myself.

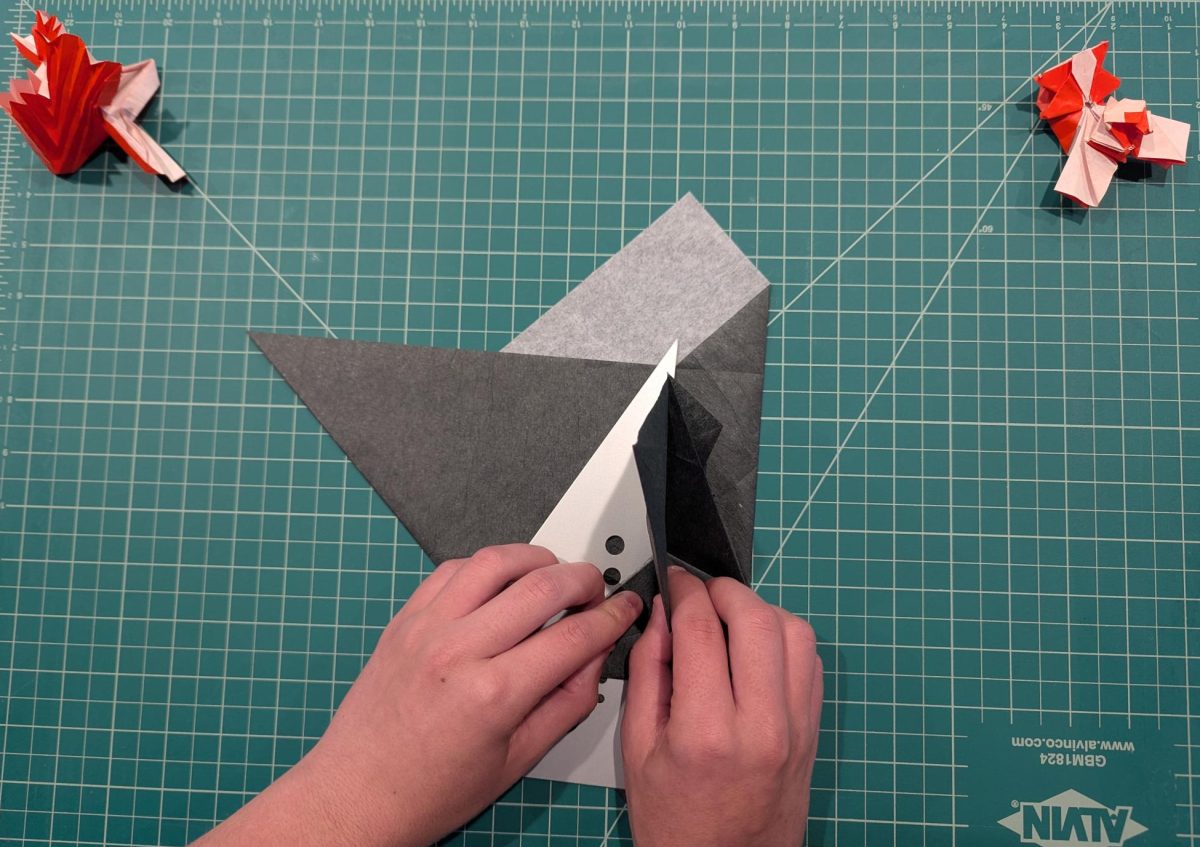

Entering high school, I found solidarity in meeting people who related to my struggle with acne. In my frequent complaints about my skin, there were times when my self-loathing journey resonated with my friends. With responses like “me too” or “same” to my rants, we found ourselves bonding over this common insecurity. Sharing our struggles with countless skin treatments comforted me, as we felt understood and less alone in our battle against puberty.

For too long, I realized that I carried more shame about this universal experience than almost all teenagers like me endure. While my initial dream was to adhere to the stereotypical standards of beauty, I eventually accepted that porcelain smooth skin isn’t a reality.

Even if it isn’t easy, accepting my skin for its natural processes is the first step in finding peace with myself. By welcoming my uniqueness, I feel a little less compelled to conform to a mold that limited my individuality. I’ve decided to embrace my current appearance, without yearning for so-called “perfect skin,” and reject the beauty standards that unfairly judge and stigmatize me based on my appearance.

I’ll continually remind myself that I’m just like any other teenager, not an outlier. Though I may never fully escape the tormenting grasp of my bumpy skin, I’ve accepted that acne is a part of the natural process of growing up, one that doesn’t define me.