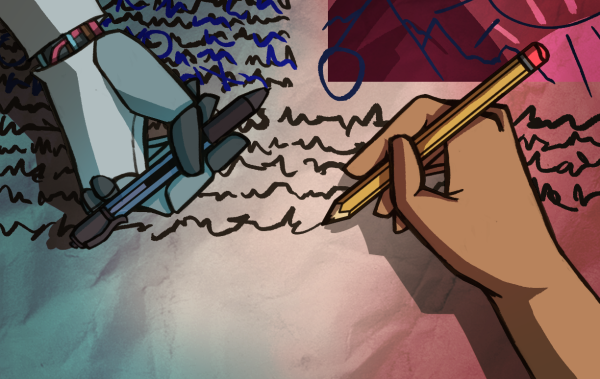

Translating under pressure

Multilingual students feel overwhelmed with the heavy responsibility of helping their parents.

Ten minutes of silence pass. Freshman Avery Kim sits beside her mother while rereading, for the third time, the medical document that a nurse handed to her. Trying to dissect each English term into its accurate Korean translation, she inhales the sterile hospital air, attempting to sort through her jumbled thoughts. Finally, Kim turns to her oblivious mother, explaining in a mumbled Korean about the chemotherapy treatment that her mother, who was recently diagnosed with cancer, would have to undergo. Since she can remember, Kim has been a personal translator for her Korean-speaking mother through each conversation or document bestowed upon them. When it came time to translate complex vocabulary, especially medical terms, the pressure rose as she attempted to communicate between languages. “They’d be asking me to read something for them and sometimes I wouldn’t be able to. I felt like I was failing them in a way.

Kim is just one of the many multilingual students at Lowell who have faced adversities when translating between English and their parents’ native languages.

A substantial portion of Lowell’s student body is composed of teenagers from immigrant families. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco is one of the largest sanctuary cities for immigrants. Due to their quicker acculturation to American customs and the English language, immigrant parents tend to rely heavily on their children for translations to their native tongue. As a result, these student translators face the pressures of succeeding academically while also assisting their parents. Their increased workload and involvement in school activities prompt these Lowell students to feel burdened by this translator role. Despite the frustration they feel, they commit themselves to language brokering as a way to help their parents communicate.

Language brokering — the informal act of interpreting and translating between family members and dominant language users — is an overlooked but prevalent occurrence among children of immigrants. According to the US Census Bureau, of the 18 million children living within immigrant families in the U.S., 21 percent live in linguistically isolated households. These are homes where no one aged 16 or older speaks English exclusively or fluently. This dependence on immigrant children to be language brokers creates a dynamic in which young people like Kim have to take on a large amount of responsibility.

Often, young people in this position feel overwhelmed with the responsibility of needing to help their parents at all times. As early as elementary school, they feel burdened with the role of translating face to face conversations or English passages to their immigrant parents. According to human development researcher at the University of Texas at Austin Su Yeung Kim, “Translation tasks could potentially create stress for immigrant youth when they lack certain vocabulary, (e.g., medical or legal documents).”

As a result of being unable to thoroughly translate legal documents or even medical treatment instructions, feelings of guilt commonly emerge among young language brokers. At six years old, junior Emerson Bonilla emigrated with his mother from El Salvador to America. According to Bonilla, translating legal documents and conversations into Spanish, while still trying to learn English himself, posed a troublesome transition process. “[My mom and father] put a lot of stress on me. They’d be asking me to read something for them and sometimes I wouldn’t be able to,” Bonilla said. “I felt like I was failing them in a way.” Similarly, Kim recalls facing complications when translating medical instructions such as the settings of an insulin pump for her diabetes or emails regarding her mother’s chemotherapy treatment. With no one to assist them at times, Bonilla and Kim, who are their family’s only children, have felt trapped in a cycle of helplessness.

As these full-time students tend to their academic workload and extracurricular activities, the added role as a personal translator takes a toll on their ability to balance each responsibility. Jessica Rong, a senior and first-generation child of Chinese immigrants, recalled experiencing the stress created by attempting to keep up with her schoolwork and meet her parents’ demands. “It does get a little frustrating when I’m doing my homework, and suddenly they have a complicated, 66-page letter that I have to translate,” Rong said. Kim agrees, believing the language barrier also interferes with her participation in school activities. As she participates in Lowell’s choir group, Kim is forced to translate more documents such as the many permission slips required for when they travel.

Despite the stress and emotional strain that they endure, these multilingual students view language brokering as a necessary act, as well as a means of repaying their parents for their sacrifices. By recognizing the challenges that immigrants face, these students hope to ease their parents’ burden. “I know that it’s hard for them because they went through so much — immigrating here and not being able to speak the language,” Rong said. “I’m paying them back for all the sacrifices they made for me.” Similarly, Bonilla acknowledges his parents’ hardships and is committed to assisting them. “In the long term, I feel like I have to be successful, so they won’t have to worry or sacrifice more than what they already have,” he said.

Many of these students appreciate their role in bridging linguistic and cultural barriers. Bonilla feels that bilingualism enables him to better relate to both the American and Latinx cultures. “When it comes to being bilingual, I’m able to connect two communities into one,” he said. “I’m able to connect a lot of blank spaces.” Understanding multiple languages has allowed language brokers to connect with people from many backgrounds, preserving cultural identity while bridging the gap between worlds, according to Bonilla.

These students also appreciate the varying benefits that come with being bilingual. Sophomore Yameen Shaikh, who translates between English and Hindi for his parents, notes that his linguistic abilities have helped him feel grounded through aiding others. “It gave me the opportunity to help others that don’t know English,” Shaikh said. “It was a privilege for me because it’s easier for some of us who speak and write.” Students also believe that their bilingual abilities have enhanced their English skills. “I feel more confident and comfortable speaking English than ever since I have that practice of helping somebody else, such as my parents, with English,” he said. This constant practice of balancing languages improves younger peoples’ executive functions and control mechanisms, according to the National Library of Medicine, while the Dana Foundation argues that bilingualism strengthens cognitive abilities like memory, creativity, and visual-spatial skills. “I know that it’s hard for them because they went through so much — immigrating here and not being able to speak the language. I’m paying them back for all the sacrifices they made for me.

The positive impacts of language brokering on teenage students are numerous, but its adverse effects require more attention. According to public opinion surveys and the Public Policy Institute of California, 73 percent of California residents are willing to pay to provide extra assistance to immigrant children by improving the academic performance of English language learners. One possibility, suggested by Shaikh, is the establishment of a city infrastructure program to better support English language learners of all ages. “The city could invest in a development center in which immigrants have a space to go and gain access to assistance with documents,” Shaikh said. “The assistants should know the immigrants’ languages, so it’s easier for them to communicate.” This government aid could extend to adult immigrants as well, reducing the responsibilities of immigrant children by providing translation services for parents who are in the process of learning English.

Language brokering affects Lowell students in both beneficial and detrimental ways. Multilingualism has many cognitive and cultural benefits, but the pressure of language brokering can feel stressful and overwhelming. Regardless of the issues that these student translators experience, they are committed to helping their parents feel comfortable and confident in their lives. Through translating and assisting, these language brokers hope to express their gratitude for their parents who overcame challenges when creating a home in a new country. “They’ve sacrificed so much,” Bonilla said. “I have to be the one that helps them get up, you know?”

Ramona is a junior at Lowell who enjoys green tea, rain, and the 24 bus. She never leaves home without her headphones.

Sierra is a senior at Lowell. She loves munching on school lunch hotdogs and updating her secret Letterboxd account. Sierra also loves sunny weather.

Katey is a senior at Lowell who’s favorite pastime is procrastinating (she is quite an expert at it). When she isn’t procrastinating, she is hanging out with her friends, eating good food, or actually doing her homework.

Vince King • May 26, 2023 at 11:38 am

I feel for these students who are under pressure to act as translators for their immigrant parents. I, too, was a child of immigrant parents, but fortunately for me, they both spoke English fluently.

There is an obligation, however, for us as first-generation Americans, to take care of our immigrant parents. They did sacrifice so much to come to the United States so that we could have a better life. I can’t imagine what my life might have been like had I been born in Communist China.

Perhaps the students can look at this as an opportunity to organize community-based translation services. My mother was fluent in Cantonese, Mandarin and English, and I’m sure she would have been happy to help out as a translator in those languages.

And there are plenty of Lowell alumni still living in San Francisco who are bilingual. Why not reach out to LAA and see if some alumni would like to volunteer to be translators?

By the way, most hospitals have translators on staff, so if Avery Kim needs help with translating medical terms and instructions into Korean, I’m sure she can ask for help.