New person, in-person: How Lowell students are adjusting to in-person learning

Senior Donna Lee stands on the sidewalk outside Lowell, admiring the campus. It’s the first day of her senior year and her first day on school grounds since she was a sophomore. Exhilaration builds as Lee walks toward the front entrance, but an overwhelming wave of anxiety crashes over her when she sees the swarm of students pouring inside. Although Lee has been eager to return to a normal school setting, she’s nervous about reconnecting with old classmates. Lee feels like a new person compared to who she was before quarantine and worries about how her classmates will view her. Thoughts like What will everyone think of me? and I hope no one remembers the embarrassing things I’ve done, fill her head as she walks in the doors.

Students have returned to on-campus learning for the first time since the beginning of lockdown in March 2020 and are reacclimating to in-person social interaction. After spending a year and a half isolated online, many students are finding that they need time to adjust, some more than others. For some students, the return to normalcy has been hindered by new social dynamics and changes in identities.

Distance learning caused some students to undergo personal changes. According to Dr. Lisa Kiang, a professor of Psychology at Wake Forest University, quarantine gave students an opportunity to become more in tune with themselves. Despite being socially restrictive, Kiang believes distance learning could have positive introspective effects on students. “I can see how online virtual spaces can lead to positive personal exploration,” she said. “I think that there is no better time than during isolation to be more self-reflective and try to use the extra time to explore what they like.”

With more time to reflect on themselves, distance learning allowed students a space to strengthen different aspects of themselves and reflect on who they were as people. Lee matured during distance learning, noting a drastic difference between who she is now and who she was entering quarantine. With increased free time, Lee strengthened her social skills by making new friends online and keeping up with her existing ones. “My extroverted personality became stronger, and I became more socially confident,” Lee said. “Since we had more time, I was able to talk to [my friends] more, which I wouldn’t have been able to do if it wasn’t for quarantine.”

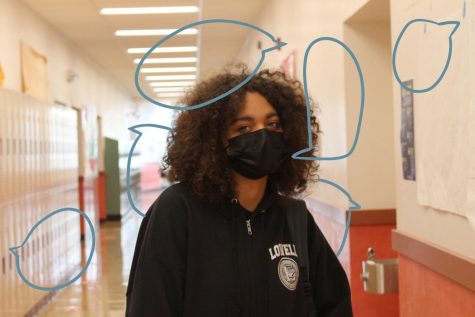

As access to in-person interaction was limited, students turned to the internet to engage with others, which opened them to new identities. For freshman Jae Muhammad, interacting with people online exposed him to a broader range of perspectives, which helped him empathize with others. “I was introduced to a lot of different types of points of views, by just being [online] all the time,” He became better at standing up for himself, yet also grew humble, learning to admit when he was wrong. Away from the social pressures of being in person, Muhammad was able to evaluate his belief system and become more reflective about himself.

While distance learning opened a window for students to reflect on themselves, it also had negative impacts on mental health. According to Dr. Caitlin Costello, medical director of the child and adolescent ambulatory services at UCSF Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital, social interaction during the teenage years is one of the most important factors of personal growth. Positive social interaction during the teenage years can reduce the chances of developing depression and anxiety, but without it, those feelings can increase. “We find that things like depression and anxiety tend to be exacerbated with teens not getting a lot of social interaction,” Costello said.

Isolation during distance learning didn’t positively affect everyone. When the pandemic began, sophomore Sebastian Sanner noticed a decline in his mental health, finding himself more irritable and angry as time went on. Restricted from social interactions, Sanner’s feelings of loneliness grew exponentially, and he was eventually diagnosed with depression and anxiety. “It was a shocker to me,” he said. “I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t expect it to be clearly labeled as a condition.” Struggling with what he felt, Sanner began keeping his thoughts to himself. He grew apprehensive about people’s reactions when he did speak. “I had more time to reflect on myself, but it caused me to second-guess myself, being more aware of how people might react to what I say,” he said.

Now, some students are struggling to transition from their distance learning experiences to an in-person reality. Muhammad became more empathetic while in isolation, a trait he wants to stay true to during the transition from distance learning. Simultaneously he is trying to readapt to the once-familiar routine of in-person learning. “It’s been hard because I haven’t been able to practice being who I’ve been trying to be in quarantine with other people around me,” he said. “Sometimes I’m scared of reverting back to my old self.” Similarly, Lee worried about returning to school with her newfound extrovertism. Because she hasn’t seen some friends in such a long time, she wants people to know that she has matured since sophomore year without blatantly stating it. “Before quarantine, my social skills weren’t the best, and I wasn’t the best at interacting with people,” Lee said. “I was scared that people would remember that Donna, instead of the Donna that I became after quarantine.”

Lee’s personal changes during distance learning have affected how she interacts with both acquaintances and closer friends. With their personalities becoming stronger during quarantine, Lee’s friend group began to branch out and expand their social circle. “People developed more strong personalities, and that changed how they interact with people they are close with,” she said. “It’s not that I got tired of my close friends during quarantine, it’s just we grew individually.”

After the isolation of quarantine and distance learning, in-person interaction has felt foriegn to some students. Muhammad feels like he is out of practice in terms of socializing with people after distance learning. According to Costello, this is normal. “People were doing distance learning for a significant period of time, and naturally, that could cause people to be out of practice with their social skills,” she said. “Having to experience additional social interactions can be a difficult adjustment for some people.” Lee has also noticed that social interaction with acquaintances is awkward, especially after not interacting with people for so long. “Catching up has been slower, since there is a lot of easing back into a familiar rhythm of talking to those people,” she said. For Sanner, it has been harder to make connections because the methods of interaction have changed, worrying that they may become permanent. “It’s hard for me to visualize social interaction fully bouncing back after COVID,” he said.

Sanner has struggled with rekindling old friendships since school returned in person. He noticed that the separation caused by distance learning and his struggles with mental health eroded his friendships. Now, after being face to face again, those friendships haven’t fully bounced back. “It makes it that much harder because I thought we were gonna go through high school together as a close group,” Sanner said. According to Costello, not socializing with friends for an extended period of time can cause rifts. “Students may have drifted apart from some friendships or peer acquaintanceships during distance learning,” she said. “Now they are having to reestablish those relationships which can be extremely difficult.”

While the transition back to an in-person setting may not be easy, students and experts alike agree that it’ll take a collective effort to progress towards comfortable interactions. Sanner thinks students need to be assertive in initiating social interaction in their communities. “The thing that picks people back up is that we have others around us,” he said. “The best thing you can do is find someone you can talk to and be comfortable around.” According to Costello, recognizing that this is a major transition and that interaction won’t be easy at first will help reduce possible social anxiety. “It may be too much to expect people to have care-free conversations with everyone they know,” Costello said. “It’s going to take extra effort at first. Interaction isn’t going to come as naturally as it did before distance learning.”

Halfway through the first semester of school, some students are still easing back into their old routines. Sanner believes they should be hopeful and know that everyone is going through the same process. “It’s been such a radical shift and I think that we can do a lot better understanding that we aren’t alone in this,” he said.

Roman is a senior who, if not chugging coffee or blasting music, is only doing one of four things: playing baseball, watching the sunset, getting hit in the head with a bowling ball, or falling asleep at the dinner table.