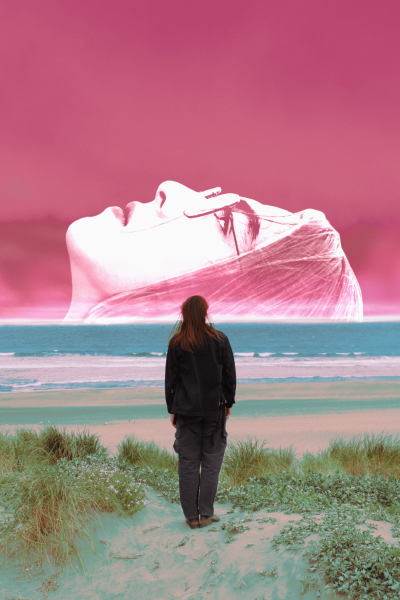

Taking back control over my voice

“Could you spell your last name for me?” The hotel concierge scrolls through their computer, trying to find my hotel room. Already stressed from the long flight and not knowing where my family is in the hotel with no way to contact them, I can feel a stutter coming on. It’s just three letters, forming a word I’ve known my entire life, but my stutter is unpredictable. My stomach drops and my face starts to get red in anticipation of the embarrassment I’ll feel once I stutter. My voice shakes on the letter “L” for 30 seconds.

I spit out the other letters while avoiding eye contact with both the concierge and the woman at the other reception desk, who is staring at me with a mixture of amusement and curiosity. The concierge thankfully ignores the stutter and hands me my room card. I turn away from them towards the elevator, my heart beating fast.

I think about my stutter nearly every time I open my mouth. During every group conversation with friends, every coffee order, every interview for journalism, the possibility that I could stutter lurks in the back of my mind.

I’ve stuttered since I was young and will stutter for the rest of my life. I won’t ever get rid or “grow out” of it. It’s generally mild, but fluctuates in severity depending on how mentally secure I’m feeling during that period of my life. On a day to day basis, the more comfortable I am in an environment, the less likely I’ll stutter. When I do stutter, I can usually predict which word it’ll be on and can use speech strategies to hide it. Since middle school, I’ve worked with a speech therapist weekly to learn about my stutter, practice strategies, and develop goals on how to not let it control me.

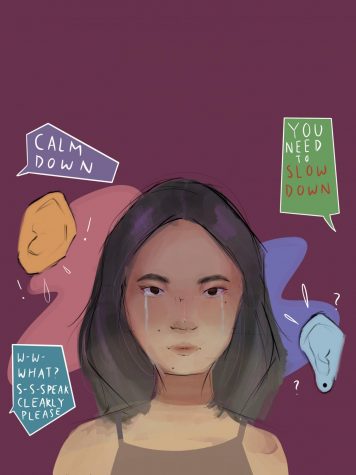

There was a brief period in the beginning of elementary school where I expressed myself with no consideration to my stutter, but that didn’t last long. I would ride out a word until the end of the stutter and not feel self conscious. But because I wasn’t trying to hide my stutter, my classmates noticed it and some teased me. A lot of people would imitate the way I sounded while working through a word. The lack of sensitivity and casual cruelty left me speechless every time. Although the jokes were fleeting, they hurt and instilled a lasting understanding in me that my stutter was something to be ashamed of.

Ableist stereotypes from society reinforced these beliefs. Stutterers are often seen as unsure of what they’re going to say or even stupid. It doesn’t matter how eloquent or insightful the words coming out of your mouth are if the delivery is awkward and clumsy. No person would want to be seen as unintelligent or overly anxious, and to have a disability that makes some people perceive me that way has made me want to reject it at all costs.

As a result, all my life, I have restricted myself from saying everything that I want to say. When I felt a stutter coming, I would just not speak. I’ve sat in class discussions with so much to say in my mind, but instead held myself back. I’ve ordered food I didn’t want because I knew I was going to stutter on the name of my actual preferred meal. In group conversations with friends, where the topics and dynamics change quickly (making it hard to prevent stutters during them), I’ve only said around half of what I want to say. I’ve spent so long sitting in fear of stuttering that I’ve let it stifle my voice.

When I did decide to contribute to the discussion, I used strategies to prevent stuttering, and if it was already happening, minimize it. One strategy to avoid a stutter is word replacement: swapping out the word I’m going to stutter on with a synonym. As someone who is very particular about saying exactly what’s on her mind, exactly the way she likes to say it, my stutter has held me back from expressing myself fully and completely on my terms.

My stutter has also deprived me of opportunities I cared about. In middle school, I was disappointed when I wasn’t chosen to deliver the graduate member speech at my choruses’ graduation. Later, I was explicitly told that I would’ve been the one to deliver it if I didn’t stutter. I was angry. As a second-year graduate member and section leader, I deserved the speech. The fact that it was only my stutter that had held me back was infuriating. This time, it hadn’t been my choice to stay silent — the choice had been made for me and I had had no control over it.

Throughout high school, I’ve stuttered particularly badly in my French class. Because I’m much less comfortable with a foreign language, I stutter intensely, especially during oral presentations. I would dread going to class, knowing that I would be called on randomly to answer a question in French. With both French teachers, I’ve made arrangements to do oral presentations and assignments in private. Learning to advocate for a comfortable learning environment for myself has alleviated some of the stress I feel from that class and has allowed me to actually focus on learning.

During one speech therapy session in winter of my sophomore year, my therapist had an epiphany. We knew from our sessions that fear of embarrassment and someone’s reaction to my stutter is what holds me back from saying everything I want to say. We also knew that I stutter the least in environments where I’m the most comfortable, like chorus rehearsal or around my best friends. So, she proposed that I try talking freely and let the stutters come out all the time. If I opened myself up to the embarrassment that accompanies my stutter — if I neutralized its power over me — I would eventually rarely stutter because I’d be comfortable in all environments.

Although skeptical at first, I tried it out on a trip to London during winter break. In a city where no one knew me, I could take as long as I needed to get a sentence out, say every single word I wanted to say, and be embarrassed in front of people I would never see again. It felt equal parts liberating and terrifying. A new city didn’t magically free me from the shame and fear attached to my stutter, though. During some interactions I reverted to my reflexes of not talking to avoid a stutter. Sometimes I stuttered and moved on without acknowledging it. And other times I stuttered and took nearly a minute to get my sentence out. I came back from the trip with more embarrassing stories, but I had discovered a different way of looking at my stutter. For the first time, it was something that I could control, instead of it controlling me.

This year, as I’ve settled into the person I’m becoming and gotten more confident in myself, I’ve stuttered less. I stutter openly in front of close friends now, taking my sweet time on even the worst ones. I allow myself to stutter a little bit in front of strangers, and even started working at a bakery where I open myself up to many opportunities for stuttering at the counter. I make casual conversation with strangers and answer their questions about menu-specific items — names I cannot replace with other words — while ringing up their orders.

In an effort to tackle the shame I still feel around my stutter, I’m becoming more open about it. When it happens in conversation, I sometimes tell people I stutter and explain quickly, even to mere acquaintances. This is a far cry from how hidden I used to keep it. None of my friends knew until seventh grade, and I remember how terrified I was to tell my best friend on FaceTime.

I know I have the strategies I need to control my stutter. I know that I have insightful things to say, that I’m eloquent, and that anyone who thinks otherwise because of my stutter is wrong.

And I also know I’ll never escape my stutter fully. I still don’t say everything that I want to say. It will take a very long time to unlearn my reflex of not speaking to avoid a stutter. I have more shame attached to my stutter than I should. And I’ll have stages of my life where my stutter will worsen again. Many more embarrassing moments are in store for me. But what’s important is that I’m not terrified of not being able to control my stutter anymore.

My stutter is here to stay, and there’s nothing I can do about that. I can choose to not let it hold me back, though. Because you’re reading this, I’ve already taken the first step in freeing myself from the shame attached to my stutter. Writing this article is another way of reclaiming its power over me, and its constraints on my voice.

Elise is a senior. This is her third year as an illustrator for the publication. Some of her interests include petting cats, going to museums, and spending unforgiving amounts of money on the evil coffee monopoly that some may know as Peet's.