A Glimpse Into Eating Disorders at Lowell

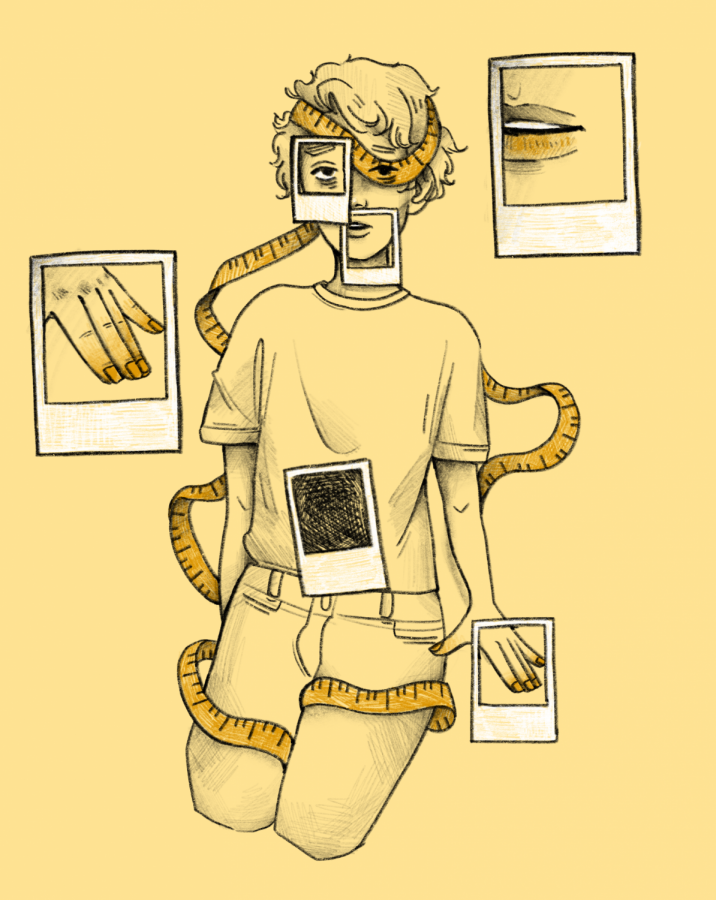

Anonymous sophomore Samantha suffers from anorexia nervosa, an emotional disorder characterized by an obsessive desire to lose weight by refusing to eat. The consequences of eating disorders can be devastating on mental and physical health, leaving dermatological effects among many others.

Sweat began to form as Samantha entered her doctor’s office. Anxiety plagued the back of her mind: she knew the nurses would notice her rapid weight loss as they took her vitals. She sat down on the table and the nurse wrapped the heart rate strap around her arm. They’ll know, she thought to herself. When the nurse checked the number that revealed itself on the screen, her eyebrows pushed together. She checked Samantha’s heart rate twice more before assuming that the machine must be broken because her heart rate was so low. A wave of relief washed over Samantha as they moved onto the rest of the checkup. But she knew that the real problem wasn’t over.

Samantha, a sophomore at Lowell who agreed to be interviewed under a pseudonym, is one of a number of students at Lowell that suffer from an eating disorder. In a survey of 208 students conducted by The Lowell in March of this year, 25.5 percent of responders said they knew someone at Lowell with an eating disorder. Commonly portrayed in the media as a way of seeking attention or losing a few pounds, eating disorders have the highest mortality rates of any mental disorder, according to adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Michelle Jorgensen, and stem from issues that are complex and multifaceted. Lowell students battle a distinct culprit: Lowell’s culture of rigor and competition has created a unique breeding ground for toxic eating habits and eating disorders to flourish among its students. Pressures at Lowell are one of the many causes of eating disorders among students, along with body image struggles, internet culture, and mental health struggles.

One of the biggest causes of eating disorders is dissatisfaction with body image, according to licensed clinical social worker Kaye Anderson, the Clinical Director of the Lotus Collaborative, which has eating disorder treatment facilities in San Francisco and Santa Cruz. According to The Lowell’s survey, 44.6 percent of responders reported that the way that they and other people perceive their body affects how much or what they eat.

Samantha grew up with poor body image that eventually contributed to her eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, which is an emotional disorder characterized by an obsessive desire to lose weight by refusing to eat. Throughout her childhood, she was belittled by family friends for her weight and identified as overweight by her pediatrician. As a result, Samantha developed harmful habits that damaged her mental health. What started as searching for weight loss tips on YouTube and comparing herself to naturally thin girls became rapid, unhealthy weight loss and nights ended by crying herself to sleep. While she dropped the weight that she had so desperately tried to lose, she never felt satisfied with her body, only growing more mentally unstable than ever before. “I was so hungry that my brain started to go crazy,” she said. “Being thin was all I allowed myself to focus on,” she said.

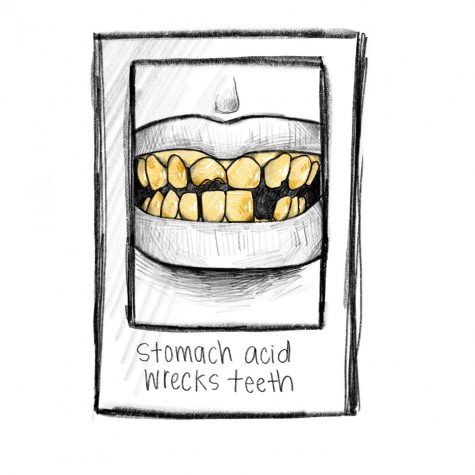

Bulimia, one of several life-threatening eating disorders that can plague a student, can take a harmful toll on the body. One consequence of the bulimic cycle of overeating followed by self-induced vomiting, purging, or fasting is the destruction of one’s teeth.

Samantha’s destructive habits are a product of societal messages that individuals with eating disorders are susceptible to, something Anderson has seen in her clients at the Lotus Collaborative. “We live in a diet culture society and there’s a lot of negative messages given to people from a young age that can then create a distorted body image, which can then sometimes lead to an eating disorder,” Anderson said.

Samantha is not the only teenager whose eating disorder was fueled by the internet. Social media platforms such as Instagram have become places that encourage body shaming, comparison, and glamorization of often unrealistic body types — sometimes fueling unhealthy eating habits in students who are struggling with or recovering from an eating disorder. Even posts that aren’t intended to be harmful can cause problems with people’s body image or relationship with food, such as celebrity posts promoting diet pills or photoshopped images of peers. Victoria, a sophomore under a pseudonym, remembers constantly comparing her body mass index (BMI) to that of Kendall Jenner. While she was underweight, she felt she wasn’t underweight enough to mimic Jenner’s abnormally small physique. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a BMI under 18.5 is considered underweight; meanwhile, Victoria idolized Jenner’s BMI of 16 that she read about online.

In addition to harmful content perpetuated by celebrities, online communities oriented around eating disorders can glorify poor eating habits. Marie, a sophomore who agreed to be anonymously interviewed under a pseudonym, started watching YouTube videos about people recovering from their eating disorders in her free time after her relationship with food started to deteriorate. Intended to inspire other people in their own recoveries, footage of content creators in the hospital for checkups was instead triggering and invalidating of Marie’s own experiences. “[The people in the videos would say], ‘Oh, I went to the hospital’… [and I would think], ‘I haven’t gone to the hospital, so I’m definitely not sick enough,’” Marie said. Furthermore, harmful content on social media can evolve into toxic communities that encourage and normalize unhealthy eating habits, like the “pro-ana” community. Short for pro-anorexia, this community consists of websites, blog posts, moodboards, and group chats of predominantly female teenagers that champion unhealthy eating habits and lifestyles. Marie would browse through these sites regularly, reading lists of eating “rules” that other users shared online. In response, Marie made her own list of rules, constricting herself to a calorie count one fifth of what a female teenager should be consuming and punishing herself for each day she broke the rule.

The manifestation of eating disorders is also often linked to other underlying mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder. This correlation has been observed by Anderson in her patients at The Lotus Collaborative. “Someone will come in with their primary issue being an eating disorder, and then when we start to look back, it’s like, ‘You were dealing with depression for much longer and this eating disorder was a way to cope with the depression and anxiety,’” she said. For Marie, her eating disorder and self-hatred revealed the true culprit of her declining mental health: depression. Marie felt that she wasn’t worthy of good health or comfort, things she associated with food, so she deprived herself of nourishment. “[My depression] was showing itself through [my eating disorder],” Marie said. It wasn’t until she got professional help for her depression that she began to return to healthier eating habits.

When certain aspects of a student’s life feel out of their control, some resort to destructive eating habits as a way of exerting control over their lives. During her freshman year of high school, Marie became increasingly dissatisfied with her plummeting grades, her social life, and her strained relationship with her parents. Being sexually assaulted by one of her best friends further intensified her feelings of helplessness. After Marie’s parents grounded her from seeing friends because of a C on her semester report card, Marie found herself lacking a much-needed support system. Feeling unable to control so many aspects of her life, Marie turned to something she could control: her eating habits. “I felt out of control, so I tried to do something that I thought would make me in control,” she said. Manipulating her eating habits became a self-destructive coping mechanism that she used to escape her living situation — at the expense of her mental and physical health.

Internal pressures to maintain control can be amplified at a school like Lowell. Fiona, a Lowell senior under a pseudonym, views the pressure she faces at Lowell as a driving cause of her atypical anorexia. When she felt like she had started to lose control over her grades and future at a school that demands academic excellence, she subconsciously found other ways to exercise control in her life by restricting her intake of calories and creating rules around food. “Being in control of your life is something that is stressed a lot at Lowell, even if that makes you sacrifice your happiness and well being,” she said.

Other elements of Lowell’s culture can encourage poor eating habits, sometimes even fueling eating disorders in students. Many students at Lowell feel immense pressure to cram more classes and extracurriculars into their schedule, oftentimes sacrificing a lunch block. Even with a lunch block, some students forgo eating in the name of academic responsibilities. In a survey conducted by The Lowell, 74.4 percent of respondents reported that they prioritized other activities over eating lunch at least once a week. For some Lowell students, satisfying their appetite takes a backseat to more pressing, academic concerns, laying the groundwork for dangerous habits to form. “The high schools that [foster] lots of pressure…I think there’s this idea of perfectionism that can go [from] academics into one’s self,” Anderson said. This culture, combined with a lack of discussion about eating disorders, makes it easier for students to develop destructive habits that go unnoticed. “I do think there’s a culture here that not only encourages eating disorders, but lets them fly under the radar for a long time,” Fiona said.

Lowell’s competitive and perfectionistic culture can grow toxic when mixed with the comparative nature of eating disorders. Samantha has several friends at Lowell who have eating disorders and unhealthy relationships with food. As she and her friends tried to confide in each other, they became competitive, mirroring each other’s destructive eating habits in an attempt to “one-up” another. “Lowell students are competitive,” she said. “We just gave each other ideas.” Anderson has also seen the competitive nature of eating disorders within her clients at TLC. Many clients feel like they are not “sick enough,” and in group therapy sessions would trigger each other when talking about their experiences. “People want to be the sickest one in the room,” Anderson said.

Getting help with one’s eating disorder is a big step towards recovery. Audrey, an anonymous sophomore at Lowell, suffered with anorexia nervosa for several years before finally getting help. After working up the courage to tell her mom and doctor about her eating habits, she was referred to a program at UCSF. Through monthly weigh-ins, vitals testing, and conversations about her mental health, she has improved her relationship with food, body image, and her general sense of self.

Even if individuals don’t seek medical help for their eating disorders, therapy has helped many people improve their mental health and work towards recovery. After two of Victoria’s close friends told her middle school counselor about her eating disorder, her parents were informed and promptly set up weekly sessions for Victoria with a therapist, which served as a space to talk about the many stressors in her life. Marie also benefited from professional help. Her psychiatrist diagnosed her with depression and general anxiety disorder, and prescribed her medication that helped to stabilize her mental health, improving her relationship with food. Anderson credits antidepressants with helping many individuals get on the path to recovery. “Some of those medications can actually help people deal with their eating disorders,” Anderson said.

An abundance of resources exist for people to get treatment for their struggles with eating. The National Eating Disorder Association holds a hotline that provides support and resources for those who need it, and can be reached at (800) 931-2237. The program that Audrey turned to at UCSF provides both inpatient and outpatient services, as well as Sutter Health and John Hopkins, which provide similar programs. The Lotus Collaborative offers meal support, individual and group therapy, psychiatrist and dietician services, and other services to lead people to recovery. At Lowell, talking to school counselors, teachers, Wellness Center staff, or any other adult, can help students get referred to potentially life-saving services and follow a path of recovery.

Eating disorders are prevalent among many students at Lowell, despite the lack of acknowledgement or dialogue that exists regarding them. They can stem from many different causes and have severe effects on the bodies and minds of those affected. Reaching out for help is a hard, but necessary first step towards recovery. “Going into treatment of any kind is really scary,” Anderson said. “You’re kind of surrendering yourself up to being told what to do.” Nonetheless, treatment is very beneficial to the journey towards health and safety. “I feel so much better than I did,” Samantha said. “With better physical health came a much, much better mental health.”