Gay Pride… Citywide?

When I was in middle school, my friends would spend hours talking about boys. I would sit quietly during conversations about who was cute and who was not, and most importantly, who we had crushes on. I wouldn’t say anything during those conversations, because I had never had a crush. I didn’t know what it felt like. Eventually, I convinced myself that having a crush just meant picking a boy I thought was nice and telling people that I “liked” him. To my surprise, the whole class believed me, and I spent the rest of middle school pretending to like boys and thinking that was all there was to it.

But in seventh grade, I got my first real crush, and it wasn’t on a boy. At the time I had a best friend, and naturally I always wanted to hang out with her. But it went deeper than that. I didn’t know how to explain it to myself; all I knew was that I really loved being around this person and I didn’t want that to stop when we graduated.

At the time, I had no idea I was experiencing a crush. I learned about the LGBT community in my seventh grade political science class, but it took almost a year after that for me to realize that I might be queer.

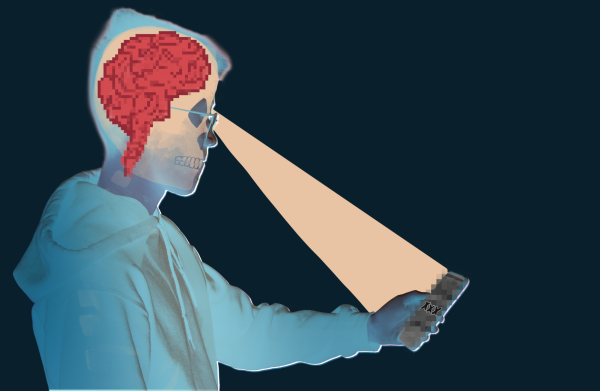

I spent the summer between eighth grade and freshman year trying to figure out if I was gay. I researched. I took online quizzes. I would imagine a girl sitting next to me, and then a boy, and try to judge how I mentally reacted to each. By the time the end of August arrived, I was certain that I wasn’t attracted to boys, but rather girls.

I was gay, in both senses of the word. Discovering my queerness made me incredibly happy. I now knew why I had never gotten a crush on a boy. But more importantly, I was just excited that I had learned about this new part of myself. I wanted the whole world to know I was a lesbian and proud.

I had convinced myself that San Francisco was this happy little bubble of acceptance and positivity where I would never experience discrimination based on my sexuality.

My mistake was thinking everyone else would be as happy for me as I was for myself. I soon came out to all of my old friends, and from my first day at Lowell I was open about being gay. I never expected any discrimination. I was in San Francisco, after all, a city known for being accepting of the LGBT community. It has been described as the “gay capital of the world.” There wasn’t supposed to be homophobia here.

Except, there was homophobia. I was just too naive to see it.

As a freshman, two major things happened to me that made me realize that there was homophobia in my community. The first was when I came out to my grandmother. She and I liked to have political discussions, and her opinions were always liberal. I thought that because of this, she wouldn’t have any objections to me being gay. So I decided to come out to her. One evening we were having a conversation in her living room, and I happily told her that I was a lesbian. To my surprise and dismay, she launched into a lecture about going through phases, the “gay lifestyle,” and teenage experimentation. She ended it by asking me, “But, don’t you want to have children?”

I had no idea what to do, so I found myself saying that I agreed with her. I was probably just going through a phase, I said. We started talking about other things, and I didn’t bring it up again. I knew that I wasn’t just “experimenting,” but I also knew that I definitely never wanted to have a conversation about being queer with my grandmother again.

The anonymous person had written my name, called me a common slur for gay people, and written some very explicit sexual harassment.

That experience shook me a little, but I soon got over it. My grandmother was old, and I should have expected that she had outdated views on homosexuality. I managed to stay positive, telling myself that at least I wouldn’t experience something like that from my peers. We were a different, more accepting generation.

I was partially right. I’ve never experienced microaggressions from people my age. Instead what I experienced was worse. Not long after the incident with my grandmother, I walked into my biology classroom to find that someone had written slurs on my desk. The anonymous person had written my name, called me a common slur for gay people, and written some very explicit sexual harassment.

Despite the fact that the insult wasn’t said to my face and the perpetrator was anonymous, the words still hurt. I remember feeling detached, because I was truly shocked to receive something like this. I didn’t tell anyone, and class was half over before I thought to erase the words. For the rest of the day, I couldn’t pay attention to my classes. And once I got home, I shut myself in my room and started crying.

I was not only hurt by what the person had written — I was hurt because they had written it at all. I had convinced myself that San Francisco was this happy little bubble of acceptance and positivity where I would never experience discrimination based on my sexuality, but that experience shattered these expectations.

In the time since those incidents, I’ve grown wiser — and more cynical. I am still quite open about my sexuality among people, but it’s not one of the first things someone learns about me anymore. I’ve taught myself to get to know someone and judge their character before coming out. For example, I am not out to my devout Catholic extended family in New York. And when talking to that extended family, I’m fully prepared to say I have a boyfriend named Emmet instead of a girlfriend named Emma.

Being gay shouldn’t be thought of as something different or wrong, but sadly, that is still the case. My city is full of opportunities to celebrate my sexuality, but I have learned that even in places like San Francisco, prejudice remains.