Cheating: Can we face the truth?

Many Lowell students have either participated in cheating or witnessed classmates copy work.

“Seatbelts fastened?” Tom, an upperclassman using a fake name to remain anonymous, asked before launching into his story.

“I remember walking in that Tuesday…and nobody was in the room,” he said. “I asked my friend to watch the door and I remember giving her a pen, and instead of her telling me when [my teacher] was coming, I told her to drop the pen on the floor so I could hear it fall. I saw the final there and I literally took it, shoved it down my pants and left. I remember I got into another room and my hands were shaking.”

Tom wasn’t caught while swiping his semester final off of his teacher’s desk. He wasn’t caught while completing it at home, while copying his memorized answers onto the exam or while looking over his 82 percent score, which he purposely lowered to “make sure it wasn’t suspicious,” on a test he said he definitely would not have passed a few days before. His teacher questioned students the next day about the missing test, but Tom had taken precautions to make sure it couldn’t be traced back to him, telling his friend to “delete the [text] conversations, delete everything,” before burning the paper final.

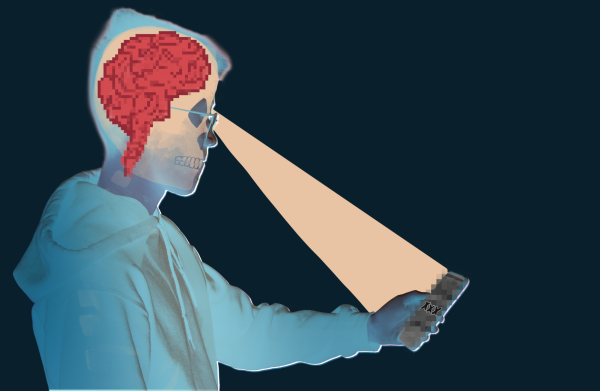

On a wall of the same classroom where Tom stole the final, a poster reads, “At Lowell, we CARE,” in which “A” stands for “academic integrity.” The acronym is overly optimistic: Tom’s story is just one extreme example of how some Lowell students have been shifting away from academic honesty. Whether it is pressure to achieve, a shrinking social stigma, a lack of oversight or all three, something within Lowell’s culture has blurred the lines between honest collaboration and outright cheating, leaving students conflicted over the importance of academic integrity.

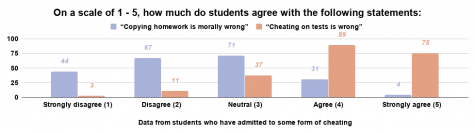

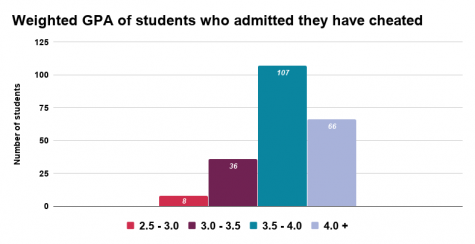

In a survey of 266 students conducted by The Lowell in April and May of this year, 82.5 percent admitted to having cheated before in one way or another. The statistics aren’t black and white: of students who have cheated on a test before, 76 percent agreed or strongly agreed that cheating on a test is morally wrong.

Even if they have cheated before, many students still believe that cheating is morally wrong.

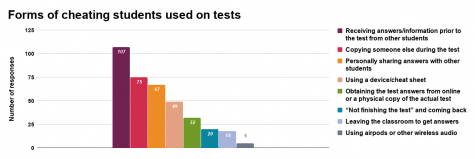

Tom is among the minority of cheaters who don’t believe that cheating is morally wrong. “I feel so great if [cheating gets me] a good grade, like morality [is] out the door,” he said. He listed off different methods he has used to cheat with an air of nonchalance that only a seasoned veteran could muster, some of which included hiding his cell phone inside of his pencil bag to read answers, concealing a sticky cheat sheet in his calculator case and writing notes and answers on his arm. His methods have even extended to once paying a peer $20 for answers to a final. Tom has a clear idea of what cheating is and how he uses it to his advantage, but other students are more conflicted about what exactly constitutes cheating.

Students like Tom have used creative methods to cheat.

As seen through The Lowell’s survey, what students “consider to be cheating” varies greatly. Responses to a question asking just this revealed that only 25 percent of students believe that “all of the above,” including copying homework, plagiarism on an essay or project, receiving answers from students in earlier blocks and sharing answers, counts as cheating. For dean David Beauvais, the definition of cheating is simple, albeit ambiguous: “It’s not telling the truth, it’s not giving an accurate representation of what you’re doing.” Regardless, students maintain countless justifications for cheating, such as teachers who assign unreasonable amounts of work or unhealthy competition between students to get high grades. Some blame the education system itself: If colleges evaluate the character of a student based off of a sheet of statistics, why should students care about anything else?

John, an upperclassman using a fake name to protect his identity, bases many of his decisions on his desire to attend a top-ranked college. When asked if it is more important to get a high grade than to learn a subject, he simply responded, “To get into college, of course [it is].” This ideology follows him through his daily life, as he chooses to copy homework and notes for some subjects–despite being caught by a teacher on one occasion–to prioritize other classes, a practice that has contributed to his above 4.3 GPA. “I find no justification for me actually doing homework when not doing it still gets me [an A],” he explained.

A campus-wide focus on grade point averages in order to get into elite colleges is a problem that Beauvais finds himself combatting on a daily basis. He believes that many students measure their value through their grades, and can feel pressured to use dishonest means to keep up their GPAs. When confronting students who have been caught cheating, he attempts to reset their priorities. “I don’t want [students’] sense of self-worth to come from grades, but from what kind of human being they are,” he said.

Most students who have cheated have above 3.5 GPAs.

John is aware that there are downsides to cheating, such as becoming reliant on a bad habit, but he holds no reservations against helping others to cheat. Whether it’s looking up answers online, which he has done on “probably almost every test,” or “letting people know what’s ahead” for upcoming exams, he continues to encourage his peers to use whatever means necessary to keep up their grades.

Students like John and Tom are members of what Tom called a “little community” of cheating, which they say fosters a sort of camaraderie in questionable activities. “We want each other to succeed and we show that through cheating sometimes,” Tom said. “People here care for other people, they understand that an ‘F’ is literally the worst possible thing in the entire world, and people don’t want you to go through that.” During tests, Tom has gone to great lengths to help other students copy off of him; in return, his peers have often held up papers for him or whispered answers his way.

Collaborative cheating at Lowell creates a self-perpetuating cycle that normalizes the issue, allowing students to speak openly about cheating and further lower the stigma behind it. Hanna, a sophomore who has also elected to use a fake name, has noticed that she and other students have become desensitized to cheating and are willing to openly discuss it. In turn, this normalcy can contribute to more students cheating, as it did for Hanna. While she used to believe that cheating was a “terrible thing that never really happened,” after witnessing it in almost all of her classes, she now occasionally copies homework herself and allows others to cheat off of her during tests. “[Because cheating] happens so often, I don’t think it’s as that big of a deal, which I know is a bad thing, but it just seems a little bit more justifiable,” she said.

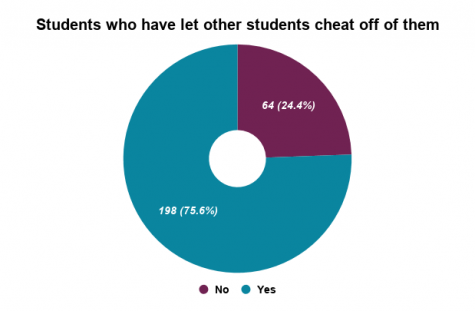

With the increasing normalization of cheating comes rising pressure on students who don’t cheat to “help out” their peers. According to The Lowell’s survey, out of students who have cheated before, 13.6 percent felt pressured to do so. For Hanna, this pressure comes in the form of not wanting to be the student who says “no” when others want to copy her answers during tests. Like Hanna, Anne, a junior who is using a fake name to remain anonymous, feels conflicted when turning down friends and peers who send her unsolicited photos of tests and other forms of “help.” “I never know how to respond to it,” she said. “Would it be perpetuating the cheating culture if I thanked [the senders], even if I wasn’t going to use their answers? You can look at it as something nice that could benefit me in the short-term, but I don’t want it. Especially not when they expect reciprocation.”

Many students have let their peers cheat off of them. While some were willing to do so, others felt pressured.

The destigmatization of cheating has been noted by students and teachers alike. Citing the recent college admissions scandal as evidence, AP physics teacher Cy Prothro believes that cheating might be destigmatized for an entire generation. “If everybody is doing it–Hollywood stars, hedge funders, lawyers–then it’s just expected,” he said. He believes that this way of thinking motivates students to cheat so that they are not at a disadvantage. “It pains me to say this out loud, but the culture now has gotten to this place where [reaching success is] by whatever means necessary,” he said.

Overall, it seems as if cheating is not uncommon, especially among high-performing, competitive students. A well-documented case of widespread and organized cheating occurred at Stuyvesant High School in New York City, an elite school with demographics similar to those of Lowell. In March of 2012, Stuyvesant’s school newspaper, The Spectator, revealed through a survey of over 2,045 students that 80 percent had cheated before in one way or another. The problem at Stuyvesant still persists today, with a New York Post headline in April of this year declaring cheating a “huge issue” for the school, and a 2018 survey reporting that 58 percent of its students had cheated on a test before.

In 2012, The New York Times pointed out an issue that both Stuyvesant and Lowell face: a lack of clear policies and punishments surrounding cheating. According to The Lowell’s survey, less than half of students know what Lowell’s cheating policy is, which is understandable considering that Lowell’s official campus policy on academic honesty is simply that cheating “in any form… will not be tolerated.” On the Lowell High School website, only Lowell’s English department provides a clear statement regarding cheating, calling for punishment “to the fullest extent of the school’s policies, including suspension for repeat offenses.” The statement also adds that “neither pressure for grades, inadequate time to complete an assignment, tests not adequately proctored, nor unrealistic parental expectations justify cheating.” According to the SFUSD student handbook, cheating and plagiarism are punishable by point deductions, zeros on assignments, lowered grades, detention, rescinded teacher recommendation letters or reports of cheating on teacher letters to colleges. Cases like Tom’s that include “stealing or attempting to steal school instructional materials” and receiving stolen materials are punishable by suspension or expulsion under California Education Code 48900.

While getting the administration involved is an option, Lowell teachers often elect to handle instances of cheating using their own discretion. As of now, Beauvais has not dealt with a single reported case of cheating since being reinstated as dean at the beginning of the spring semester. He believes that teachers are well-equipped to handle situations of cheating, and can account for factors that administrators might not be aware of. Conversely, this policy (or lack thereof) can also lead to confusion and difficult decisions for teachers who are faced with serious instances of cheating in their classrooms.

Last school year, Prothro had to navigate a sticky situation after being tipped off by a student that a sophomore had “stolen” a final and distributed it to others. The College Board AP Physics test that he was using was meant to be a confidential teacher resource, but it had been leaked online and found by the student in question. Without clear guidelines to follow, Prothro “agonized” over how to punish the student, who ended up with a zero on the final and a C in the class that he was set to ace.

While Prothro decided that the stolen final was an isolated incident, other teachers have dealt with more widespread or ambiguous cases of cheating that have caused entire classes to retake exams. Last school year, Tom was a part of a group text chat of precalculus students who sent photos and answers for their tests between blocks. This semester, his former teacher, who declined to comment on the situation, chose to have multiple blocks of her class retake an exam due to the persistence of this form of cheating in her classroom. Similarly, in early May, English teacher Stephanie Crabtree made her AP English classes retake a test after being made aware of cheating. In an emailed statement to The Lowell, Crabtree wrote that, in following the English department’s policy on plagiarism and academic dishonesty and the AP Exam security guidelines, she felt that a retake was the fairest way to address the matter. Nevertheless, this decision proved to be controversial. Junior Kelly Ye, a student in her seventh block class, felt like she was being unfairly punished for the wrongdoings of other students after being satisfied with her self-earned score, and was angry with any students who cheated for not considering the consequences of their actions.

Some teachers have more rigid cheating policies. Retired social studies teacher Steven Schmidt taught at Lowell for over 20 years, and in a statement to The Lowell he expressed his belief that all students who cheat should be expelled. “If Lowell is truly preparing students for college, [students who cheat] should be forced out of Lowell’s prestigious environment to enroll in a different school,” he wrote. He believes that following this policy would force students to recognize the risks of sacrificing their academic honesty. According to Schmidt, the last two students who were caught cheating in his AP United States History class were offered an ultimatum: earn an “F” on their semester grade, or drop his class to enroll in regular US history. “Neither of them ever came back to my class,” he wrote.

While many teachers have their own cheating policies worked out, some believe there is room for more oversight by the administration. AP environmental sciences teacher Katherine Melvin gives around 20-30 zeros to students that she catches cheating each semester. While she believes that this system works to discourage students from cheating, she says that she would be “surprised if she caught 10 percent of cheating. Melvin thinks that the school should instate clearer policies for teachers to follow. “I don’t feel that there are clear guidelines or clear support at any level,” she said. “It’s unfortunate because it would be really nice if every teacher really clearly understood what the steps in the process are.” According to Melvin, this lack of support leads to “tremendous variation” in control over cheating between teachers.

According to Hanna, her world languages teacher has witnessed widespread cheating in her classroom since her freshman year, but has done little to stop it. In this class, Hanna has long been a source of answers for other students due to her fluency in her foreign language. Though her teacher has moved Hanna closer to her desk, Hanna still finds herself surrounded by cheating classmates during tests. “There have definitely been times where people will be blatantly looking over my shoulder and just be standing there, looking at my test for long periods of time, or will come up and take a picture, and my teacher won’t say anything,” she said.

Tom feels that he and other students are more willing to cheat in classes with teachers who provide lax punishments or who don’t look out for cheating at all. He doesn’t attempt to cheat while his teachers are actively supervising classrooms; in contrast, he described his experience last school year when his teacher was absent during a final: “We were like, ‘I guess we’re cheating today, guys,’” he said. “We went in a clockwise position exchanging tests and we all got like an 80 percent on it.” Beauvais described a lack of teacher supervision as an “attractive nuisance,” explaining that teachers who don’t actively look out for cheating can be encouraging academic dishonesty.

For students, the punishments for cheating are inconsistent, but for teachers, the mental conflict of punishing students can take a consistent toll. When she catches students cheating, Melvin struggles with her perception of both her students and herself. “[Confronting students about cheating] turns you into an evil person,” she said. “I don’t like the person I’ve become and I know [students] don’t like it either. When we catch cheating, all of us feel so dirty. But it exists here.”

There might be disparities in how cheating is punished, but Beauvais doesn’t believe that a harsher or more uniform policy around cheating would resolve the issue. His guiding principle is that people who don’t cheat do so because they recognize the deeper consequences of cheating, not because it’s against the rules. “I think we all know that cheating is wrong,” he said. “We all knew it was wrong when we were [children], and we will know that it’s wrong when we’re 75 years old. Consequences be damned, people will do what they want.” Additionally, he has found that something as simple as a sit-down chat with a student can yield positive results, as he is able to recommend tutoring, negotiations with a teacher and a chance to discuss “what grades actually represent.”

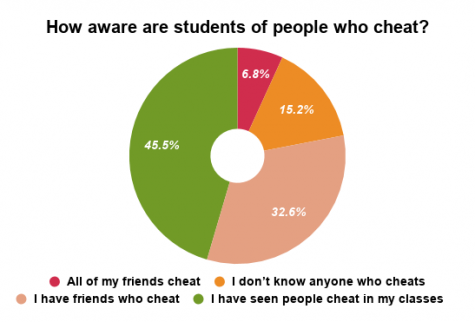

Most students say they have seen people cheat in their classes.

One way to reduce cheating might be increasing communication between students, teachers and administrators. Melvin has long been calling for a “deeper conversation” about the emphasis on grades and the amount of homework given at Lowell, which she believes will shed light on sources of student stress and consequently lower levels of cheating. Similarly, Beauvais believes that there should be more than the minimal amount of collaboration currently happening between administers like himself and teachers in dealing with the situation. For now, teachers like Prothro and Melvin have been experimenting with less grade-focused curriculums, such as a self-grading program that Prothro tested out last year. While few teachers have found success in such strategies, there are ongoing efforts to change what educators like Prothro believe is a flaw in the culture of both Lowell and outside society.

No matter the justification, rationalization or excuse a student gives for cheating, Beauvais wants to remind them that they are responsible for their actions. “The opportunities for cheating are myriad, but whether or not you cheat is not necessarily dependent on that,” he said. “It ultimately resides with [your] choices about [your] character or life. Winning at all costs is not worth winning. It really is not. At the end of the day, you’re empty. You’ll never know your true potential. What you earn is not who you are, you’re buying a trophy and saying you won, it’s not the same.”

It is difficult to pinpoint the perpetrator and the victim in the game of cheating. Are students playing against a broken system or are they cheating themselves out of an education? Is cheating simply an immoral deed, or as freshman Taytum Wymer puts it, “dumb [and] against the rules,” or a necessary evil, as Hanna rationalizes due to the pressure and workload that she endures? Either way, Lowell’s student body’s view of cheating seems to have changed over recent years. “I mean, how did the culture evolve the way that it has?” Prothro asked. “That’s sort of the million-dollar question.”