Seeing through the smoke: How the Camp Fire shook my world

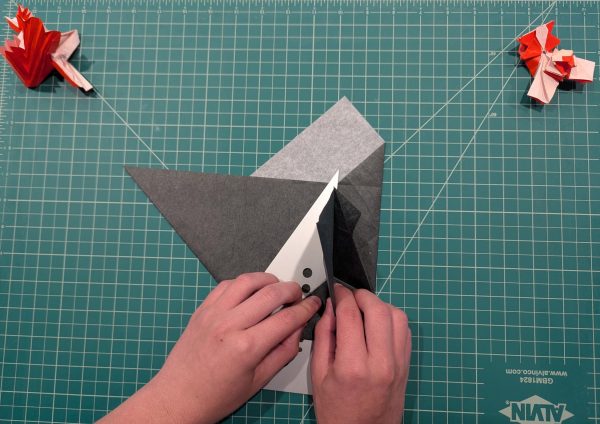

Olivia Sohn Image of smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California taken by class of 2018 Lowell alumna Olivia Sohn, who volunteered for Marin County Search and Rescue. Smoke from this fire made its way to Lowell’s campus in 2018.

After several hours of driving and a quick Starbucks run, we drove past the flashing lights and police cars that marked the restricted area where civilians and even property owners were not allowed. Only Search and Rescue (SAR) vehicles, fire crews and PG&E trucks drove these roads. Already we were driving through blackened fields that seemed to stretch into infinity. Charred trees dotted the horizon, partially concealed by the thick smoke. We were in Paradise now, a short week after the Camp Fire had largely destroyed the small town.

Marin County Search and Rescue had brought me to many places around California to search, but I had never been to an area ravaged by fire before. Driving into Paradise, I thought I had signed up to spend several days there, but little did I know, Paradise wouldn’t leave me for months.

I went to Paradise along with hundreds of search and rescue members from across California. We participated in some of the largest searches in California history, helping clear Paradise of hazards, as well as searching for human remains, before the residents could return to their homes.

Paradise felt like another planet. The smoke was as thick as fog, turning the sun bright red. It was unnervingly silent and completely deserted except for the occasional cat or blackened deer roaming the desolation. This was a world of grey, black and white, everything dusted with a layer of light ash. Large holes of burning soil formed smoking craters in the ground. Some stumps and fallen trees were still flaming, but that didn’t worry us. What surrounding them could they catch on fire? A pile of ashy rubble?

I was constantly aware of the hazards facing us. We had received a warning from the leadership on our team about our exposure to carcinogens, but that was the last thing on my mind. Power lines with only the bases charred tilted precariously above us, their wires hanging low above the road; those that had fallen formed tangled messes on the ground. I scanned the trees above me, searching for “widow-makers”—stray branches blown into neighboring trees by the strong winds of the fire. If they fell on us it could be fatal.

One of my team’s assignments was to help search all of the cars for human remains, firearms and other hazards, so that they could be cleared from the roads. With about 50 other searchers we achieved this in one day. Melted aluminum streamed away from many cars in bright ribbons and the windshields formed warped green moldings on the dashboards. Some of them appeared to have swerved to the side of the road, with their doors open, as if people had thought it better to run than drive. I contemplated where those people had gone. In another car? Was it that bad that they had to run for it?

Once, as we searched some cars in a driveway, I came upon two dead cats laying on the concrete. The cats weren’t piles of ash, but blackened forms frozen in their position of death: paws outstretched and curled, mouths open. I concluded that death by fire had to be the most painful.

As we searched houses the next day, we sifted through the ashes of people’s lives. We could recognise what used to be a refrigerator, a gun safe or a metal cabinet, but what would really offer a window into the who the homeowners may have been were random untouched objects found amidst the rubble. I found what appeared to be children’s pottery: a candle holder and pinch pot, completely intact, resting in the ashes. Outside another home, I found a beautiful untouched statue of a crane inside a charred sculpture garden. It was the last thing left standing besides their chimney.

When our work was done, I was ready to leave Paradise, but I wasn’t ready to leave my team, the ones who understood the world I had just been immersed in. The color, vibrancy and standing homes of the towns we drove through on our way home felt foreign.

I wasn’t at home for more than two hours before I hopped onto a plane to North Carolina for Thanksgiving. In the following weeks, I realised my relationship with Paradise hadn’t ended when the searching was over.

When I was in Paradise, I felt relatively untouched by the destruction that I was witnessing. I knew it was a horrific situation, but I had a job to do, so I didn’t allow it to affect me. But now in North Carolina, I found myself deeply sad about everything I had just witnessed. My family showing me copious news articles about the fire didn’t help; learning about the people who died running from their cars or sleeping in their beds made me attach these victims to all the objects that I had seen.

Searchers wore tyvek suits, hard helmets, rubber gloves, clear goggles and masks to protect themselves from the hazards facing them. At the end of every day, searchers were required to clean off in decontamination stations and change their clothing.

When we were driving around Charlotte, I began to feel like Paradise was tacked to the back of my eyes, like a filter overlaying reality. I’d see burnt houses everywhere, their bathtubs full of rubble, the beds reduced to blackened springs and the warped kitchen appliances. The images overwhelmed me, trapping me in the grey space between reality and memory.

I thought that when I returned to San Francisco I would feel better, but I didn’t. The bouts of anxiety and the images didn’t leave me. On my first day back at school, as I was walking on the smooth grey concrete, I was reminded of the sidewalk we found two dead cats on and I saw them lying before me. My brain hurled back to images of them, then to images of Paradise. And while I knew where I was, again, I felt stuck in the grey space. My entire body became tense, my breathing and heartbeat rapid.

The rest of the week didn’t get better. Classmates and teachers asked where I had been, as I had been gone for a week. But each time I told them, my heart seized up and I felt trapped all over again.

In the weeks following the search, my existing depression was reaching new lows. I felt trapped in a dark hole I couldn’t get out of. I tried to talk about my experiences with close friends and loved ones but talking about it didn’t help because it caused me so much anxiety. I felt isolated from everyone in my life. It became difficult to sleep. A seemingly random fear of being murdered would shock my body awake every time I turned off the light, so I slept with it on. Even when I did sleep, it was restless. Dreams about Paradise visited me nightly. I struggled to keep my grades up and things I used to enjoy now scared me, so I stopped doing them. Would I have a flashback if I started a bonfire or went on a walk on the beach? Even when I was relaxed I felt like the feeling could end at any second; I was constantly aware that beneath the surface lurked Paradise, threatening to show itself.

After around a month of this, I called my best friend’s mother who is a therapist. She referred me to a specialist in treating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

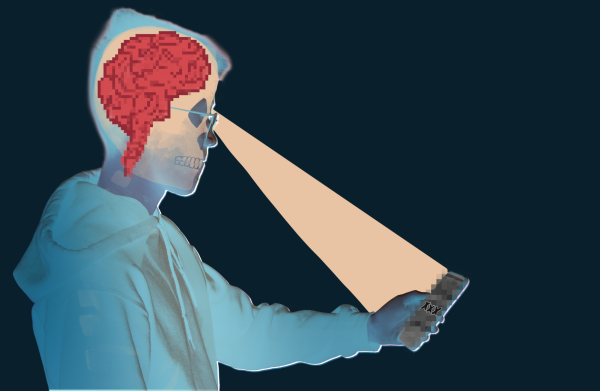

PTSD is categorised as an anxiety disorder caused by trauma. According to the National Center for PTSD, four symptoms of PTSD include avoiding reminders of the trauma, feeling anxious or on edge as well as hyper-vigilant, re-experiencing the trauma through dreams or flashbacks and suffering from negative thoughts and feelings. PTSD is the dysfunction of two parts of your brain: the amygdala, which triggers your flight or fight instinct, and the prefrontal cortex, the part of your brain that makes decisions. According to Psychology Today, people with PTSD have a hyperactive amygdala and a less active prefrontal cortex, which means that their brains overreact to their environments, while their prefrontal cortex is less able to mediate this stress response.

The therapist that I went to specialises in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy (EMDR), an eight-stage process designed to help the brain naturally heal from its trauma.

EMDR helped me, and eventually I stopped having flashbacks and learned how to deal with the anxiety that I was experiencing. The last flashback I had was in late February. The bad dreams rarely visit me, and it’s now unusual for me to have nights where I have trouble sleeping. The hypervigilance, however, was slower to leave and I felt it for months after I ended therapy.

I had difficulty coming to terms with my PTSD. I felt weak for getting it because I didn’t find human remains, or fight the fires. I carried a sense of shame about it, but slowly that lessened as I accepted that I had no control over it.

Recently, after months of feeling unable to participate in search and rescue, I went to a Monday night meeting and now I’m considering starting to search again.

My case of PTSD was mild because the trauma that I experienced was a short and isolated event. For people who experience trauma repeatedly, or more intensely, PTSD is something that can haunt them for years, for some until the ends of their lives. I am very lucky to have been able to receive support and quality treatment so quickly.

While I feel that mentally I have healed, the experience has left scars that have shifted my values. I say scars not in a good or bad way, just to say that my experience with Paradise and PTSD have deeply changed me. Both the issues of climate change and PTSD have become very important to me.

In California, because of climate change, the magnitude and frequency of wildfires is predicted to increase drastically. We’re already seeing this damaging pattern in the Northern California fire storm of 2017 and the Camp Fire last year. I have now experienced first hand the horrific death and destruction that climate change is already bringing, leading me to question my career path in the social sciences and consider switching to a STEM major to study climate change.

In the months following the Camp Fire, Paradise clouded my mind, but I’ve emerged from the smoke with a clearer understanding of my values, ambitions and the ways in which I want to make a difference.