Why are teen driving rates going downhill?

Driving used to be a right of passage for teenagers. Getting a license meant gaining a certain freedom that childhood never had. It meant being more independent. However, things have changed. Developments in technology, transportation and new parenting strategies have all contributed to a significantly lower driving rate in high schoolers, including those in San Francisco.

Nationally, driving rates of teens and young adults fell 15 percent from 1996 to 2015, according to MTF. This led to a reexamination of the drivers ed requirement in San Francisco Unified School District. In 2008, a meeting of the San Francisco School Board addressed the lack of interest in student driving. The issue was brought to their attention by San Francisco student delegates who didn’t want to be required to take a drivers education course. The board ultimately decided to abolish drivers education as a graduation requirement. They justified this by saying that getting rid of drivers education allowed San Francisco to be more eco-friendly, by eventually having fewer drivers and thus fewer cars, and giving schools more room in their budgets.

Driving was much more popular, however, just 30 years ago. Lowell teacher Brian Danforth went to Lowell as a teenager and learned to drive there in the ’80s. He recalls that most of the kids he went to high school with were set on getting their licences as soon as they could. Now, Danforth doesn’t see nearly as strong of a desire in current Lowell students to do the same. “I haven’t gotten a sense from students that there’s a massive demand for [drivers education],” Danforth says.

Additionally, Danforth believes new parenting styles have added to the decreased driving rates in current teens. “Generally speaking…I think a lot of parents [30 years ago] wanted their kids to be more independent,” Danforth said. “Whereas I think now there is the term ‘helicopter parents,’ where parents are a little bit more willing to be carting their kids all around to soccer practice and then to band practice and to whatever other things that they do.” Danforth believes that the rise of overprotective parents has contributed to students not feeling a need to be more independent; since they already get a ride most of the time, the kids themselves are less willing to learn how to drive.

Jaymie Frazier, a Lowell counselor, also believes that the desire to drive among students has gone down. In the three years she’s worked at Lowell, Frazier has only had a handful of people ask about a drivers education program. One reason for this, she thinks, could be whether or not the student’s family actually has a car. “Some families don’t even own a car and they solely use our public transportation,” Frazier said.

Some teens simply have no interest in learning to drive at this point in their lives. Senior Ben Lanir feels this way. He thinks there are better uses for his time at the moment, such as his participation in robotics and academic commitments. Senior Maya Terplan plans to wait to get a driver license until she turns 18 because she believes the process will be shorter then, as adults are not required to do 50 hours of behind the wheel driving practice.

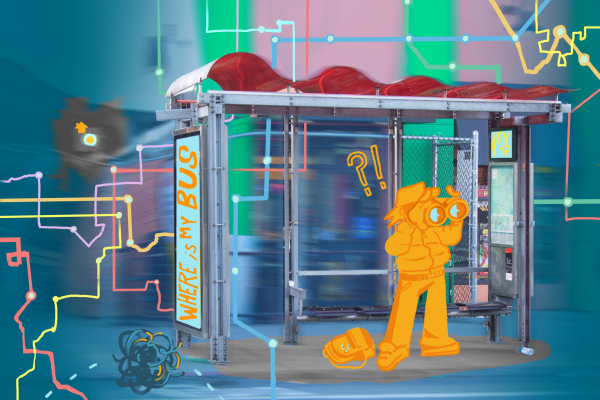

One reason San Francisco students aren’t interested in learning to drive is the public transportation available to them. The San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency (SFMTA) has become a good alternate option for young possible drivers. “It would probably take just as long to get to school with a car than it does with the bus,” said Terplan. Lanir agrees with Terplan. “San Francisco does have a lot of public transportation,” he said. “And I’ve never had real issues getting to where I need to go by public transportation or the occasional rideshare.”

Students who might otherwise drive also often use paid ride or rideshare services such as Uber and Lyft. s of 2016, there were over 45,000 Uber and Lyft drivers in San Francisco alone, according to the SF Examiner,. These services offer an easy way to get from place to place.

Parking, more specifically the lack of it, has repelled many families from owning a car in San Francisco. The trouble with parking has impacted Terplan and is part of the reason she is putting off learning how to drive. “I know where we used to live in the city, parking was really difficult,” she said, “So many families here have trouble finding parking.”

Some students also don’t learn to drive for economic reasons. Lanir doesn’t want to raise his parents’ insurance, as car insurance for young drivers is typically expensive. According to the Incharge Institute of America, adding a teen driver to a typical car insurance plan can rate the cost by 44 percent. This is because teen drivers are four times more likely to crash than older drivers.

Other students put off learning to drive due to driving’s environmental impacts. Terplan has been hesitant to drive, despite recently inheriting a family member’s car, because she has been raised to dislike cars due to their environmental impacts. “We’re trying not to harm the planet more,” Terplan explained. She thinks one reason for fewer teenagers driving, especially in San Francisco, is that they’re more aware of the environmental damage cars create.

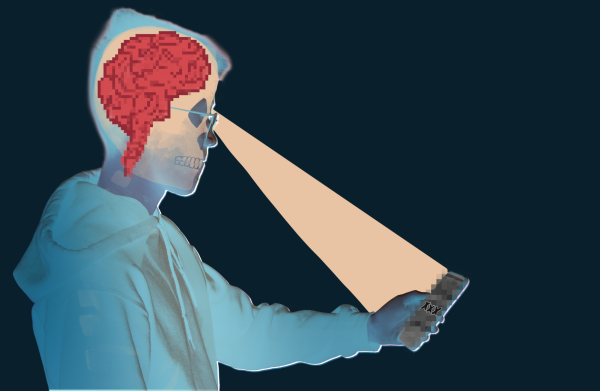

Another big factor lowering student driving rates is the internet. Streaming a movie instead of going to a theater, facetiming a friend rather than meeting in person, ordering online instead of going to a store and more are all opportunities for people to stay home instead of driving. As internet availability and usage has gone up, driving rates have gone down, according to the Pew Research Center. “The new reality is that as people create social networks in technology spaces, those networks are often bigger and more diverse than in the past,” the Pew article claims. The internet and social media indirectly lowers driving rates in young people by decreasing the need for face-to-face interaction.

The decreased driving rate in teens has not gone unnoticed. The Lowell dean, David Beauvais, has issued only two campus parking permits to students this semester, as of April 2019. Both Lanir and Terplan have also noticed an overall lack of interest in driving, each knowing only a handful of people out of the 700 seniors at Lowell that have started the process, let alone gotten a license.

A possible way to increase driving rates in teens could be to reimplement a drivers education program into SFUSD. However, Lanir doesn’t believe having such a program at Lowell would encourage students to learn. “Honestly if there was drivers ed, I’m not sure if I’d take it,” he said. “For me, personally, I think it’d be interesting, but not interesting enough to take if it weren’t required.” He doesn’t believe that others would want to take the class either, as most people he knows have trouble fitting everything they want to take into their schedule already. The only way the class would get enough students to remain an option is if it were to become a requirement, and he understands that those courses aren’t taken too well by the student population.

Modern developments have made teens less willing to learn to drive, and the driving rate will most likely only continue to decrease as teenagers use the internet more and travel less. While Lanir doesn’t believe this is something to be alarmed about, Danforth is unhappy that fewer young people are learning to drive, as he believes driving teaches many necessary lessons. “It’s one of those rights of passage that is good for young people to just learn responsibility,” he said.