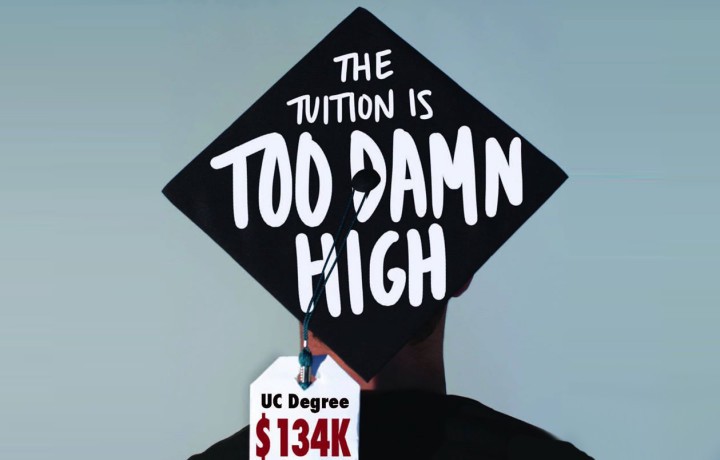

The tuition is too damn high: how students cope with the rising cost of a UC education

In March of 2013, Brian Nguyen logged on to the UC Santa Cruz portal to find an acceptance letter. This was the moment he had been waiting for: University of California (UC) schools are a dream for many Lowell students and now it had become a dream come true for him. He was ecstatic — until he realized that he may not be able to attend Santa Cruz. After all, could he really afford a UC education for all four years?

The cost of attending college has only risen over the decades. Tuition at a private university is over twice as expensive as it was in 1984. Tuition at California public universities, like UC schools, has increased more than at public universities in any other state over the past decade. That brings the cost of attendance at a UC school — which includes tuition, fees, housing, books, health insurance, transportation and other expenses — to about $33,600 per year when living on campus, higher than it has ever been in previous decades.

UC schools’ priority is “to ensure that a UC education remains affordable to all Californians who meet its admissions standards.” A big part of that is their “reaffirmation of California’s long-time commitment to the principle of tuition-free education to residents of the state” in accordance with the 1960 California Master Plan for Higher Education, a plan that defines the specific roles of California’s higher education programs, including UC schools. However, the current tuition price freeze for Californians, enacted through the 2015 state budget, will only last for two years and after that the price of UC attendance could potentially increase even more.

The cost of attendance at a UC school is higher than it has ever been in previous decades.

This is an issue for Lowell, where UC schools are extremely popular options. Just last year, 545 students out of 642 students — about 85 percent of the graduating class — applied to at least one UC school, according to the UC admissions website. Additionally, the same dataset shows that Lowell garners the highest number of students accepted into a UC of any high school in California, with a 76 percent overall acceptance rate.

Despite these high statistics, if the prices continue to rise, many Lowell students may not be able to afford attending a UC school: 43 percent of Lowell students qualify for free or reduced lunch, meaning that their low-income status hinders their ability to fork out the high tuition fees.

Financial Aid

Fortunately, financial aid options are plentiful for low-income students, as compared to students from more affluent families. Existing financial assistance ranges from grants and scholarships, which do not have to be repaid, to loans, which do have to be repaid. To apply for financial aid from the federal and state governments and from most colleges, students have to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which determines how much financial aid each student’s family needs.

However, the complexity and low completion rates of the FAFSA form has plagued high school students, parents, counselors and legislators alike and makes applying for financial aid difficult. The FAFSA form currently consists of 105 questions and California’s completion rate is a measly 43.5 percent, according to Bellwether Education. This has prompted calls on Congress to pass a bill that would simplify the application.

The FAFSA form currently consists of 105 questions and California’s completion rate is a measly 43.5 percent.

Of the three types of financial aid, loans are the riskiest because they put students in debt. However, the federal loans that are obtainable through FAFSA are still a valuable form of financial assistance and are recommended over private student loans. “Federal student loans are cheaper, more available and have better repayment terms than private student loans,” according to FinAid, a website that guides students through the financial aid process.

Although many students may turn away at the possibility of being in debt, counselor David Beauvais believes that student loans can be reasonable if they pay off in the future. “Good debt is an investment in your future or your present,” he said. To help students decide for themselves whether their college tuition and student loan debt is a worthy investment, last month the U.S. Education and Treasury Departments released a federal college scorecard detailing many statistics, among which are the average student loan debt and the earnings after graduation.

Transferring

Options beyond financial aid also exist, as Nguyen, Class of 2013, who was accepted to UCSC but was unable to afford a four-year UC education, found out. Nguyen’s solution was to transfer: first attending the City College of San Francisco for two years and then transferring to a UC school. And it paid off. As of fall 2015, Nguyen is officially a student at UC Berkeley.

“Community college is much cheaper and you can still transfer to the college you want. You’re paying two years for tuition — it’s college on sale.”

In choosing to transfer instead of attending a UC for four years, Nguyen is now able to attend UC Berkeley for much less. The total estimated cost of a four-year UC education is $134,400, including room and board, supplies and transportation. In comparison, students who transfer after spending two years at CCSF pay a total of $92,032–31 percent less than the four-year total. Counselor Jonathan Fong believes that transferring is a viable financial option. “Community college is much cheaper, and you can still transfer to the college you want. You’re paying two years for tuition — it’s college on sale,” he said.

Nguyen’s choice benefitted him in more ways than just the financial. The numerous extracurricular opportunities available in San Francisco led Nguyen to believe that going to CCSF instead of a UC school outside of San Francisco was worth it. While attending CCSF, Nguyen worked as a lab technician intern at the Exploratorium, a research intern at UC San Francisco, Mission Bay, and a mentor and lab aide at the CCSF biology department.

Part of Nguyen’s learning experience at CCSF stemmed from his interactions with the diverse student population. At CCSF, he met a lot of parenting students, returning students and immigrants who worked two jobs while also attending school as full-time students. “It’s taught me humility and how to value your education,” he said.

Transitional Issues

“Students themselves tell me that they feel like ‘I’ve cheated because I’m not here for four years.’”

However, some transfer students do encounter transitional issues when trying to balance their workload and social life, according to Jannet Ceja, UCSC’s Services for Transfer and Re-Entry Students (STAR) program coordinator and advisor. In order to address these students’ difficulties, some schools offer in school services, like STAR, which host academic workshops and classes to help students with the transition.

Although some transfer students have also confided that they feel out of place at UC schools, the worry is unfounded, according to Ceja. “Students themselves tell me that they feel like ‘I’ve cheated because I’m not here for four years,’” Ceja said. “But most students here know who the transfers are so they try to be inclusive.”

Transfer Admissions Guarantee (TAG)

For students who specifically aim to transfer from a California Community College to a UC school, a built-in program exists. The Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG) program offers California Community College students guaranteed admission and first priority in transferring to one of the six partner UC schools: UC Davis, UC Irvine, UC Merced, UC Riverside, UC Santa Barbara and UC Santa Cruz.

Transferring to the other UC schools, UC Berkeley, UC Los Angeles and UC San Diego, is not guaranteed but definitely possible. In fact, UCLA, a non-TAG program school, was the UC school with the most transfers in 2015, with 3,226 transfer students. Furthermore, considering that the new state budget requires that UC schools admit a third of entering students as transfers, transferring is a valid option.

When Ngai transferred she was one of the few juniors who had all her lower divisions finished, allowing her to focus solely on her upper division courses.

In her senior year, Jasmin Ngai, Class of 2012, was pondering over whether she should take the risk of carrying a huge student debt burden out of a four year UC education. Realizing that taking advantage of the TAG program would allow her to pay less for a UC education, Ngai first attended the City College of San Mateo before transferring to UCSD (back when UCSD was still an option under the TAG program).

Choosing to transfer from the TAG program instead of going straight from high school to a UC benefitted Ngai beyond the monetary savings. The TAG program requires that students fulfill their general education course requirements — classes that give students a basis in the major academic disciplines of science, social science, humanities and fine arts — before transferring. When Ngai transferred, she was one of the few juniors who had all her lower divisions finished, allowing her to focus solely on her upper division courses, courses that relate to her major. “In fact, I can practically finish college early if I wanted to,” Ngai said.

Ngai also stressed the importance of self-discipline and self-direction in attending a community college because college advisors expect students to take responsibility for their own planning process. “College advisors aren’t similar to high school counselors,” she said. “They may assist you, but all the hard work and planning solely depends on the individual.” It was the promise of the TAG program that motivated her to finish her general education courses within two years by carefully planning her semesters at community college. Her personal and academic growth, as well as the money she saved, leaves Ngai to believe that the TAG program was the best program her college experience has offered her.

“Use the time spent at community college wisely because this is your second chance to prove yourself that you are worthy of attending a UC.”

The TAG program is also a route to a UC school for students who are not ready to attend a UC straight out of high school. Throughout her high school career, Sally Zhou, Class of 2011, had always seen UC schools as an ideal, but in her senior year she did not feel that she had the appropriate mindset or the necessary grades to go. Upon discovering the TAG program and that transfers from California Community Colleges are admitted to UC schools at a rate over nine percent higher than the average transfer, Zhou decided to give CCSF a chance.

Zhou did not waste the opportunity to prepare for a UC. “Use the time spent at community college wisely because this is your second chance to prove yourself that you are worthy of attending a UC,” Zhou said.

Zhou views her experience at CCSF as valuable, even finding some of the courses at CCSF preferable to UC courses. “The science department at CCSF is phenomenal and in fact, after transferring to UC Davis, I realized that the foundation I had in general chemistry, biology, organic chemistry and physics prepared me very well for upper division courses when I transferred,” she said.

The Bottom Line

However, for students who do not or cannot attend a UC school for whatever reason, financial or personal, there is no need to feel pressured. There is popular notion around high school students that persists, which states that the only road to success is through an elite university education. A New York Times article addressed this myth earlier this year with examples of students who graduated from mid-tier colleges and were just as successful as some of their elite university graduate counterparts — concluding that a student’s growth at a college is more important than the name of the institution itself. Beauvais’s own experiences testify against the supposedly all-consuming importance of a university’s reputation. He began his higher education at a community college, which turned out to have as “equally excellent” of an education as the four-year state school he transferred to. Ultimately, the name of a school does not determine students’ future. “In this office, counselors have gone to Stanford, Princeton, prestigious schools. But look — now we all have the same job, and get paid about the same,” Beauvais said.

Originally published on October 16, 2015