Finding Equity, Part 1: African-American students share their stories of problems with Lowell’s…

Midway through her freshman year at Lowell,

Chrislyn Earle, who is now a senior, was contemplating skipping school. She had come from the 220-student Mission Dolores Academy to Lowell looking for a new challenge, and a new challenge she got. “At first I didn’t try to make friends with people of different races because I was very scared, intimidated,” she says now, looking back on her freshman year at Lowell.

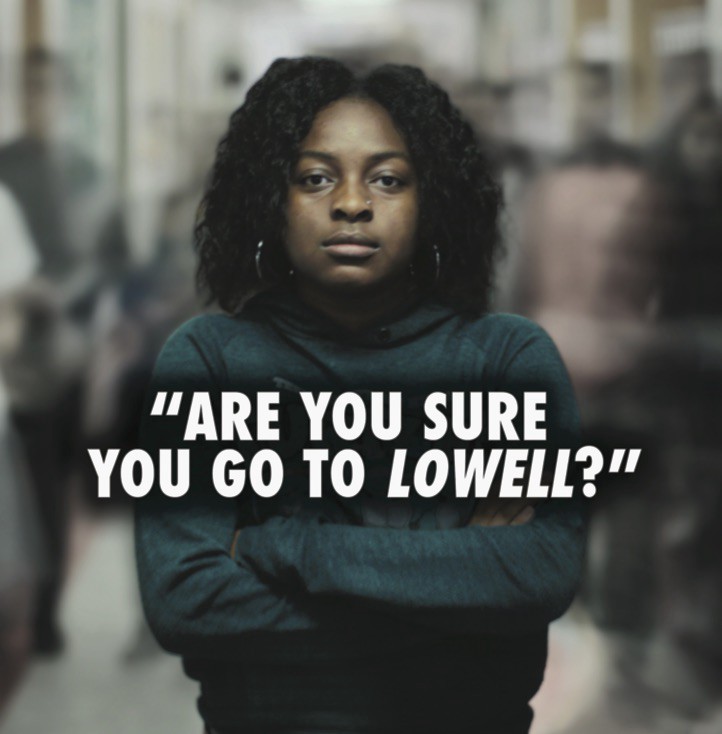

“If you talk to another person or an adult, and you say that you go to Lowell and you’re black, literally their facial expression is in shock, ‘You go to Lowell? Are you sure you go to Lowell?’”

The low number of minorities at Lowell means that some African-American students are the only students of their race in their class, which some, like Earle, find uncomfortable. In fact, there were only 61 African-Americans out 2,718 students last year, a mere 2.2 percent, compared to San Francisco Unified School District’s (SFUSD) 10 percent. The African-American population at Lowell has not exceeded three percent since the 1999–2000 school year and it seems that number is only decreasing — African-Americans only make up one percent of the current freshman class.

However, this trend is misleading without understanding that Lowell’s African-American population has remained the same despite recent decreases in the district, according to principal Andrew Ishibashi. In the 2001–2002 school year, when Lowell’s African-American population was two percent, 15 percent of the SFUSD population was African-American. On the other hand, last year, even as SFUSD’s African-American population dropped to 10 percent, Lowell’s African-American population stayed at two percent.

Yet the fact remains that some African-American students who are accepted to Lowell continue to choose not to enroll. This year, 15 African-American students were accepted into the freshmen class. Of those, only nine African-American students actually enrolled at Lowell, a mere one percent of approximately 680 freshmen, according to Ishibashi. The disparity between the number of students accepted and number enrolled this year suggests African-American students, who could or are attending Lowell, have concerns that are not being effectively addressed. After all, the enrollee to acceptance rate for African-American freshmen this year is 10 percent less than the enrollee to acceptance rate for the whole current freshman class, which is 70 percent.

In response, the school has made efforts to discover why minority students choose not to attend Lowell. In 2010 and 2011, students involved in the school’s youth leadership organization Peer Resources, led by coordinator Adee Horn, visited several middle schools with student populations that have high percentages of African-American and Latino students. Concerns that eighth-graders pointed out included transportation time, the workload, academic difficulty and that there weren’t a lot of their people of their ethnicity or race.

Self-Segregation

Earle’s struggles in her first year at Lowell exemplify why minority students may not want to come to Lowell. Before attending Lowell, Earle did not research the school and did not know much about it. She was understandably surprised and overwhelmed when she came to Lowell from Mission Dolores Academy, where 25 percent of the student population was African-American. “I didn’t really talk to that many people and I was not happy at Lowell because I was still not comfortable,” she said. “I was not having fun like everybody else was. When I was in class I was alone. No one really helped me.”

“I was not having fun like everybody else was. When I was in class I was alone. No one really helped me.”

This was compounded by the fact that Earle experienced other students self-segregating and leaving her out when choosing groups for projects. “I think that was the hardest part of freshman year, but also just being invisible already,” she said. “The worst part is walking around asking people and you get rejected or they are avoiding you so that you won’t be in their group.”

In fact, 42 percent of students at Lowell see segregation by race and ethnicity when students choose their own seats in class, according to the YouthVoice survey administered by Peer Resources last month. The same survey also found that 57 percent of Lowell students saw segregation by race and ethnicity during students’ free time.

Self-segregation is especially relevant at Lowell, the largest high school in the city, with a population of over 2,600 students. The bigger the school population is, the more racial segregation occurs and the fewer interracial friendships exist, according to a 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Speaking Up

Fortunately, in her sophomore year Earle became accustomed to Lowell and got advice from her mother to complete her classes and open up. “I was comfortable and I wasn’t afraid of my classes even though I was the only black person because I had to get used to it,” she said. “I would raise my hand and ask and answer questions, which is key because you need to make yourself known.”

“Having diversity will help you in your high school life and it will allow you to see the different kinds of people there are.”

After making friends of different races, sophomore Chy’na Davis felt more welcome at Lowell. Davis met her diverse group of friends when she attended a summer algebra program hosted by Lowell before her freshman year. Their friendship continued into the school year. “What holds us together is just our personalities,” she said. “I began looking at other characteristics, so that it wasn’t anymore about what’s on the outside, but rather what is on the inside.”

Davis believes that having friends from different backgrounds is important in understanding different points of view as well. Her Filipino friends teach her about their culture, traditions, and language. “Having diversity will help you in your high school life and it will allow you to see the different kinds of people there are,” she said.

Sophomore Chet Okorie made friends, who are of Filipino descent, on the first day of school in his English class and has stuck with them throughout his Lowell career because they make him laugh. Okorie’s friend sophomore Tyler Vicente said that race does not matter in their friend group; instead, it’s other qualities, like a sense of humor and a willingness to play basketball.

Academics

Unlike Earle, junior Tsia Nicole, who is now co-president of the Black Student Union (BSU), was already familiar with being one of few African-Americans at school and the only one in many classes. She came from Roosevelt Middle School, where only 6.6 percent of over 700 studentsare African-American.

“Just because you’re a different race than me and I’m black, doesn’t mean you’re superior to me in any way. I realized that I got into this school just like you and if I put in my best I will get the best outcome.”

At Lowell, however, Nicole still encountered the same difficulties that many freshmen, regardless of race, experience: the challenging academics. “Freshman year was kind of hard because middle school was easy so I didn’t have to spend much time studying or doing homework and I still got good grades,” she said. Fortunately, by sophomore year, Nicole became accustomed to Lowell’s workload and completed her transition from middle school to Lowell smoothly.

Lowell’s reputation as an academically challenging school reaches students even before they attend. These stereotypes can act as a barrier to African-American admission into Lowell, according to Nicole. “I think the main reason why minorities don’t want to come is because they hear how difficult the school may be,” she said.

When Earle talked to African-American peers about attending Lowell, their immediate response was to say that Lowell would be too hard for them. Adults perpetuate the same stereotypes. “If you talk to another person or an adult, and you say that you go to Lowell and you’re black, literally their facial expression is in shock,” Earle said. “‘You go to Lowell? Are you sure you go to Lowell?’”

Sophomore Golden Landis von Jones found rumors of failing grades to be misleading and wasn’t discouraged. “Before I came, even after I was accepted and planned on going here, I had people telling me, ‘Oh, your GPA is going to drop a ton and you’re going to do bad and fail,’ but none of those things happened,” he said.

Earle’s experience at Lowell began to improve after she gained confidence in her own academic abilities. After realizing that she was getting the same grades — and even higher — than everybody else in class, her mentality changed. “Just because you’re a different race than me and I’m black, doesn’t mean you’re superior to me in any way,” she said. “I realized that I got into this school just like you and if I put in my best I will get the best outcome.”

Cultural Appropriation

Stereotyping African-Americans and such misunderstandings can be caused by a lack of exposure to minorities, according to Earle. “Sometimes our peers here don’t mean to be semi-racist or stereotypical, but there aren’t a lot of us, so they are only able to address us,” she said.

“Sometimes our peers here don’t mean to be semi-racist or stereotypical, but there aren’t a lot of us, so they are only able to address us.”

The graduating class board found themselves in a controversy over cultural sensitivity last month while conducting the Senior Pop Polls, a survey that is published in the yearbook. The polls allow seniors to nominate the seniors of their choice to specific characteristic categories — one of which this year was “Most Ratchet.” In African-American culture, where the term originated, ratchet is extremely derogatory. In a recent New York Magazine article on the word “ratchet,” Michaela Angela Davis, an image activist and former fashion editor of Vibe, said, “there’s an emotional violence and meanness attached to being ratchet, particularly pertaining to women of color.” Earle found “Most Ratchet” category in the Senior Pop Polls offensive. “Here at Lowell, they think being ratchet is being loud, or vibrant, or outspoken,” she said. “But it’s actually akin to having a category “like ‘Most Asian’ or ‘Most White-y.’”

After the Class of 2016 Board was notified about the negative connotations of the word, the Class of 2016 Board decided to remove the category from consideration. In a letter to the editor, the Class of 2016 Board apologizes for their actions, stating that they never intended for the category to offend anyone.

These types of misunderstandings can make African-Americans feel unaccepted in the Lowell community. Cultural appropriation is a sociological concept that considers the adoption of a culture’s elements in another culture to be a negative occurrence — especially when the borrowing culture has oppressed the people of the culture it’s borrowing from. In particular, Halloween costumes of Native Americans headdresses, Middle Eastern turbans and other cultural dress have faced criticism.

Cultural appropriation of clothing items also occur in fashion trends. One such fashion trend that exists at Lowell are dashikis, which are contemporarily worn on special and religious occasions in African-American communities. “People wearing dashikis have no idea where it came from or why it is significant in black culture,” Nicole said. Ignoring the cultural meaning behind cultural traditions can offend people, even if it’s unintentional. A non-black student “who wore a dashiki came up to some of us, because we were talking about the dashiki, and said, ‘Oh, are you guys trying to copy me?’” Earle said.

“Here at Lowell, they think being ratchet is being loud, or vibrant, or outspoken.” But it’s actually akin to having a category “like ‘Most Asian’ or ‘Most White-y.’”

Even parents are reluctant to allow their children to attend Lowell in fear that the school may not be able to understand the needs of their children. “Most minorities’ families are scared about most of Lowell being Asian or white because they feel like their child won’t be supported or helped out here,” Earle said.

Counselor Adrienne Smith, the sponsor of BSU and the only African-American counselor at Lowell, has spoken to parents of minority students who seek academic support for their children. “I tell them about the various supports we have in place, like our CSF tutoring, our Peer Mentors, our counselors, our teachers that have office hours for kids to empower themselves,” she said. She also mentions the Study Skills class that helps students transition from middle school to Lowell and the Wellness Center, which is available throughout the school day to offer emotional and mental support for students.

BSU also aims to provide a safe and welcoming space for fellow minority students to ease their transition to Lowell and improve their years at Lowell. “We have fun and learn about black culture from current events or past situations: discussions that we most likely wouldn’t be having in our normal classes, but are equally important,” she said.

Current events that BSU has brought up in conversation include the heavily publicized Michael Brown case, in which an unarmed African-American male was shot by a police officer in August of 2014. BSU also discussed the infamous shooting of Oscar Grant, an unarmed African-American man, by a police officer in Oakland in 2009. Nicole wants BSU members to explore social issues that African Americans might have to deal with in society, like police brutality and modern racism.

Davis finds the discussion that BSU offers valuable because there are certain situations that only people of the same race have experienced. “Everybody knows about it, but talking to people who understand it helps you more than talking to a person that heard about it but has never experienced it,” she said.

After joining BSU in her sophomore year, Earle became so involved with the community that she is now vice president of the club. Her experiences have taught her that African-Americans face a steep battle to overcome stereotypes and have to support themselves and each other. “I just know that as an African-American at Lowell, we have to make a stand, make ourselves known and give 110 percent all the time in our school work, because otherwise people are going to underestimate us,” Earle said. “That’s in life, not just at Lowell.”

Nia Coats, Ophir Cohen-Simayof and Whitney C. Lim contributed to the reporting for this article.

Originally published on November 25, 2015