Junior Violette Walenne sees a video of a gua sha, a facial sculpting tool, pop up on Instagram Reels. The influencer in the video praises the product for its ability to depuff and sculpt your face, claiming that purchasing this tool will instantly improve the user’s appearance. Hoping to achieve similar results, Walenne buys the product. She had never paid attention to anyone’s puffy face before, but now she feels that she needs this product. However, she has not used the gua sha since purchasing it. In an attempt to feel less wasteful, Walenne decides to keep the product in case she does use it, and has owned the gua sha for three years without once using it. The trend of overconsumption has made her buy yet another product that she does not need.

Like many Lowell students, Walenne has contributed to overconsumption: the unnecessary purchasing of non-essential products. With social media in the hands of many teenagers, advertisers have seized the opportunity to target adolescents by exploiting their developing decision-making skills and influencing them to buy products. Teenagers, who are now getting their first jobs or starting to acquire money, are spending it to purchase items that they may not need, but have been convinced to buy through advertisements and other influences.

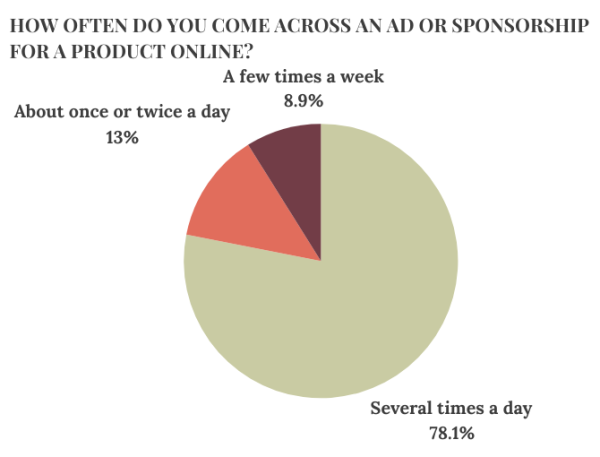

The rise of social media has fostered an increase in product sponsorships, advertisements, and other online promotions. Most advertisements that catch teenagers’ attention come from social media. In a survey conducted by The Lowell in November 2024, 78 percent of students stated that they come across an ad or sponsorship several times a day. Teenagers’ overconsumption of products has caused many to develop unsustainable spending habits and unhealthy views on money and possessions.

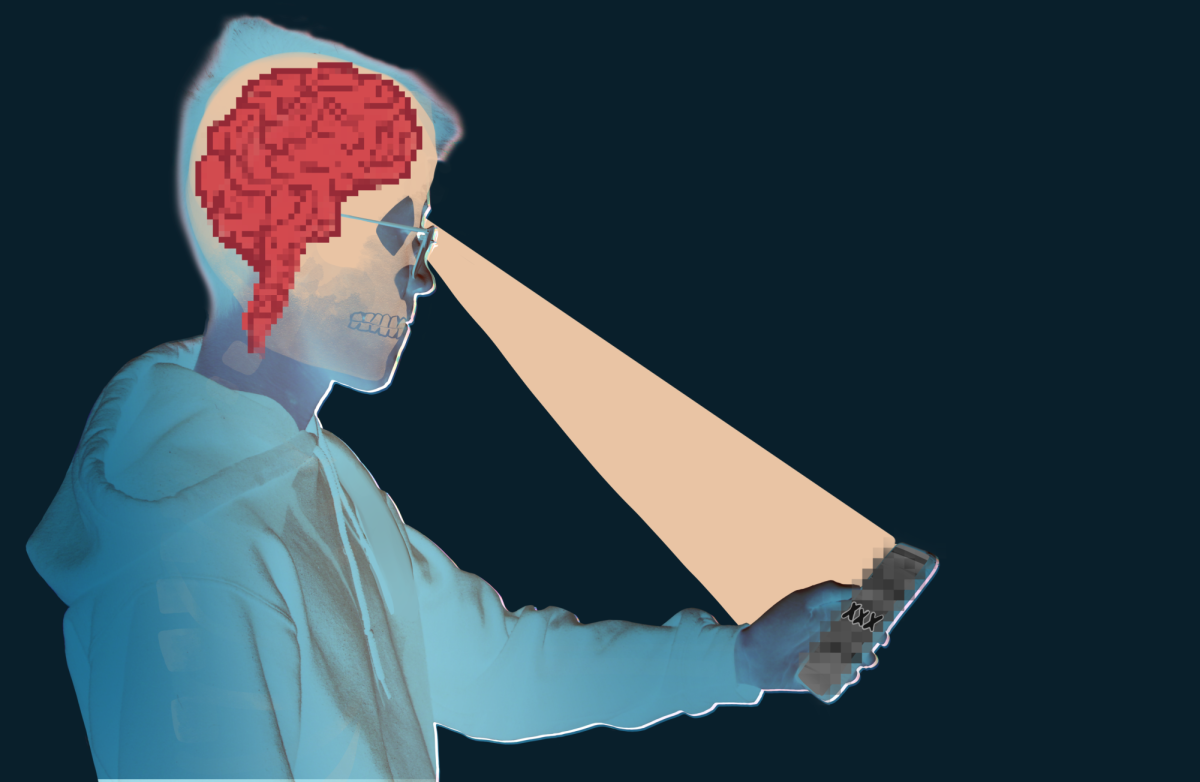

According to Dr. Allen Kanner, a psychologist and author of Psycholgy and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World, overconsumption is defined as the buying of things that you do not need, but have been manipulated into believing will improve your life. “The meta-message is that if you have a problem, buy a product to solve it,” Kanner said. According to Kanner, the rise of teenager-focused marketing started around the 1980s, when teenagers began to possess more disposable income and advertisers began targeting them through television advertisements. As teenagers spend more time on social media, advertisers and companies have shifted their focus to advertising online. “Huge amounts of information are gathered on teenagers online,” Dr. Kanner said. “These data are then used to identify exactly what a teenager’s current interests and desires are, [and] the marketing is tailored specifically to these needs and desires.” Companies and social media apps such as Instagram and TikTok also use influencer sponsorships to convince people to buy their products. Influencers are paid to advertise products, whether by directly addressing the audience about what the product can do for them or simply placing it in the background of a post to display their partnership. TikTok Shop, Tiktok’s e-commerce feature, allows content creators to easily market and advertise sponsorships and brand deals. However, it is often not disclosed to the viewer that the creator is getting paid to advertise the product.

The growing accessibility and convenience of online shopping over the last few years has exacerbated its use, leading to high rates of overconsumption. According to a survey conducted by The Lowell in November 2024, 35 percent of respondents stated that they most commonly used online websites or social media to buy products. Lowell Psychology teacher Dina Yoshimura believes that the COVID-19 pandemic influenced this increase in online shopping. “Everything could be delivered to your door,” Yoshimura said. “I could get a quart of Baskin Robbins ice cream delivered to the front steps in 20 minutes.” Junior Kinza Hussain feels that Apple Pay and other forms of online payment have made it easier to purchase items online. “It’s so much easier to just click buy, and buy a ton of crap you don’t need,” Hussain said. While people could get turned away by the time required to travel to a store and buy something, the ease of browsing and selecting a few buttons online have made shopping extremely convenient.

Many Lowell students find themselves buying products they do not use to keep up with trends they see on social media. Ivan, a student under a pseudonym, feels that many teenagers follow these trends because they feel the need to fit in with their peers. “I think a perfect example of this is the Stanley Cup. People want the brand name and to fit in,” he said. Ivan himself has been influenced to buy an excessive amount of skincare products by social media influencers. “They’re like, ‘You want to achieve this certain look? Then buy this product,’” Ivan said. However, once Ivan buys these products, he often realizes that he doesn’t actually need them, but he still attempts to make use of these products. “I feel like it’s a waste to buy it and then throw it away,” Ivan said.

According to a survey conducted by The Lowell in November 2024, 49 percent of respondents stated that they shop most often at malls and outlets. Many Lowell students engage in overconsumption through purchasing products at malls such as Stonestown. Hussain finds herself buying food or clothing at Stonestown Mall, a seven-minute walk from Lowell, at least three times a week. She often sees products online and visits the mall hoping to purchase something similar. “You start looking for things that are similar, and then you’re like, oh, it’s not that expensive,” she said. On one occasion, she bought multiple articles of clothing at Stonestown, just to regret her purchase once she got home. “I made the decision [to purchase an item] because I was seeing a lot of people wearing it, even if it didn’t really fit me well or look nice on me,” she said. Ivan feels that Stonestown’s proximity to Lowell has caused him to buy food and drinks when he does not need to. “I spend at least 100 dollars a week just going to Stonestown,” Ivan said. Hussain also believes that the close proximity of Stonestown has been a factor driving her purchasing habits. “It’s just so convenient and I think it’s hard not to just go, especially when you have nothing to do,” Hussain said.

A major contributor to overconsumption is the relatively low price point, quick manufacturing, and accessibility of many products advertised to teenagers. This is especially prevalent in the fast fashion industry, which is defined by Vogue Magazine as “quickly produced trends sold at low price points.” Since teenagers do not have as high of a budget as many adults, they are less likely to purchase long-lasting, quality clothing due to its high price tag. Students like Walenne find that microtrends – short-lived trends that are promoted on social media – are a major contributor to fast fashion, causing them to turn to thrifting clothing instead. “Recently, TikTok and all the short-form content has been speeding up trend cycles,” Walenne said. “Things are going in and out of style faster, and everybody’s overconsuming things that they’re not going to use in a couple of months.” Some Lowell students, like senior Allie Dillick, choose to thrift clothing with the intention of purchasing better quality items for a cheaper price, while believing they are helping the environment. Dillick rarely finds herself buying new clothing. “The reason I like thrifting is because all my thrifted stuff lasts so much longer,” she said. “If you make durable goods, more people will stop buying non-durable goods.”

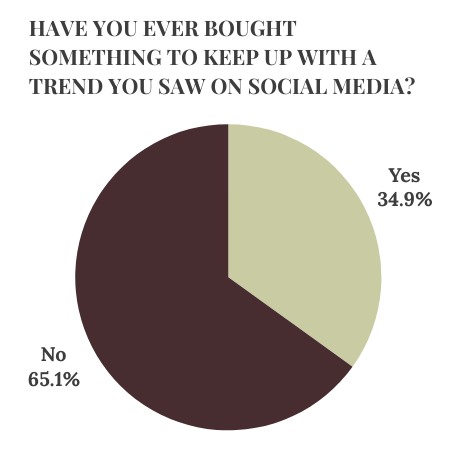

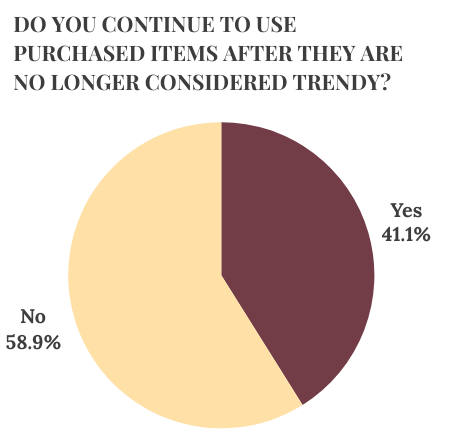

While many teenagers justify purchasing non-essential products by donating them after a certain amount of time, product donation does not truly fix the problem of overconsumption. Most of these products end up in the landfill and are detrimental to the environment, and these donations do not guarantee that a consumer will not buy more. In a survey conducted by The Lowell in November 2024, 35 percent of respondents stated that they have bought a product to keep up with a trend seen on social media, and 59 percent of respondents said they stopped using a purchased product after it was no longer trending. Hussain finds herself giving away her clothing and other products once she can no longer find a use for them. “I’ll try and donate [clothes] because I know that there’s no point in just tossing it away, and I know maybe somebody else will like it, or I look for friends who might want it,” Hussain said. Some teenagers that purchase clothing from thrift stores believe that as long as items are donated, it is not harmful to the environment. However, according to Yoshimura, donating unused clothing is not without cost. “Students will buy something and wear it a couple of times, and then they donate it thinking that donating is going somewhere good,” she said. “In reality, I think we’re just adding to the pile of garbage that we have on this Earth.”

The 2024 Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) was passed by the U.S. Senate in an effort to prevent companies from profiting unfairly off of minors. The act is intended to prevent minors from seeing advertisements showing illegal products, and enforces social media platforms to opt minors out of personalized recommendation advertisements. However, companies like Google and Meta have been accused of exploiting this loophole in an effort to attract those aged 13 to 17 from target platforms like YouTube and TikTok. Many social media accounts that have not been age-verified fall under the “unknown” category, which contains high numbers of users under 18. Because those under the “unknown” age range are not protected in the same way as those who have accounts identified as a minor, they are still exposed to targeted advertisements. Walenne believes that companies are targeting vulnerable teenagers in an attempt to maximize profit, and feels personally targeted. “People aren’t really aware of how they’re being played by all these companies, because the way that they market their products is that they are selling an idea,” she said. “These companies are selling ideas to teenagers who are especially vulnerable and impressionable.” Dillick agrees. “Companies need money,” she says. “So they are like, ‘you need more.’”

According to Dr. Kanner, young people tend to be less enamored with the American economic system than their parents and grandparents. Kanner believes that this difference is likely due to them coming out of high school or college not yet able to financially support themselves. “We need a much more compassionate type of economic system…that is dedicated to making sure everyone in the society has at least a minimum amount of support so that they can live a dignified life,” he said. “And that isn’t subjecting [teenagers] to this endless barrage of marketing in order to get them to feel bad about themselves.”

Financial education, which is the knowledge that helps one make informed decisions regarding money, is an important factor that can impact a teenager’s ability to make wise spending choices, but is hardly present in student curriculums. According to Mr. Marshall, an AP Economics teacher at Lowell, budgeting and saving are important skills to acquire, but most economics classes do not have room to include them. AP College Board guidelines do not include budgeting, and regular economics classes last only a semester, so it can be hard to fit in anything outside the curriculum. Yoshimura is a firm believer in financial education for teenagers, but she finds that high school curriculums are already constantly overflowing with material, leaving little space for new additions. “Students need economics and American government, and four years of English, and three years of math,” Yoshimura said. “Where are we going to fit this in?” However, Yoshimura believes these classes should be made a priority, believing that teenagers are still children who need guidance to make proper decisions to set them up for the future.

Marshall believes that it is beneficial for students to understand how the economy works, as it can help them make smarter financial choices. “Telling students that [it] can be damaging if you’re overspending and not thinking about what you’re spending your money on, and what that can mean for your long term financial well-being and stability, is a tough thing because [spending] is, I think, part of American culture,” Marshall said.

Even if financial education is not incorporated into school curriculums, Yoshimura believes that it is important for teenagers to address their spending habits themselves. She urges students to be more conscious of the products they invest in, and to practice self-awareness. “There has to be self control,” she said. “You have to learn how to limit yourself [and be] aware of, ‘what is this product, what are they trying to do?’” According to Hussain, she often consults a friend before deciding to spend money in an effort to spend less. “I think that if I didn’t have somebody to try and keep me in check, I would probably be spending a lot more,” she said. However, she believes that the decision of purchasing a product is ultimately up to the person themselves.