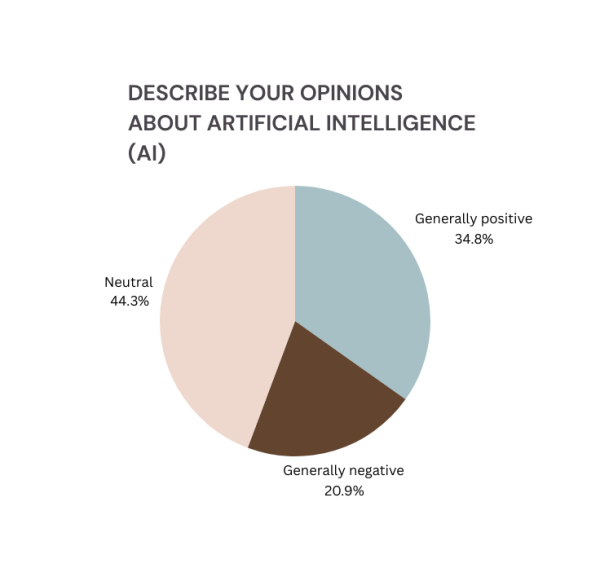

From cheating with ChatGPT to chatting with Character.ai, Lowellites — and young people globally — have been incorporating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into their routines. The increasing prominence of AI has fundamentally changed many students’ current lives and even their plans for the future. Some students are enthusiastic about technological breakthroughs with AI. Some are interested in studying and developing AI. Still, others are lamenting their job prospects as AI takes over human positions in more and more industries. The future of AI is hotly contested, and these debates can be overwhelming. Instead of focusing on the overarching arguments about AI, The Lowell spoke with five students to provide their perspectives on the impact of AI on their present and future.

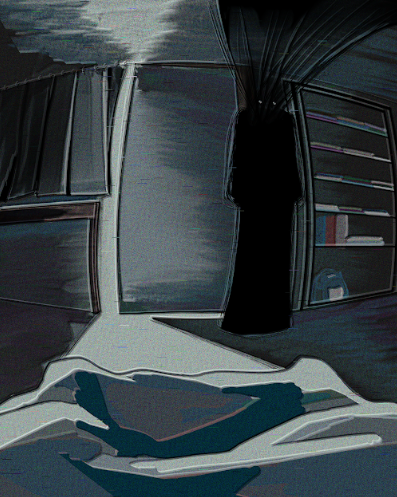

Senior Logan Ragland, a prospective film student, is feeling the pressure of AI encroaching upon artists’ territory. Film incorporates various artistic disciplines, like photography, music, digital art, and theater. For Ragland, the real meaning of film, and art as a whole, is the creative intent of those who made it. AI-generated media, he argues, eliminates this intent entirely and thus removes the value of art.

Ragland has a strict definition of art, and it doesn’t include AI. “I don’t personally believe that AI can make art,” Ragland said. Art is a form of self-expression, according to him. Because AI creates media based not on self-expression but on averaging data points, AI-generated media doesn’t hold the same weight. “It doesn’t matter if it looks like art,” he said. “It necessarily lacks that certain emotion to it.” As AI-generated media becomes increasingly indistinguishable from human-created pieces, Ragland worries about the integrity of our appreciation for art. His concern isn’t unfounded: in the 2022 Colorado State Fair art contest, an AI-generated piece won first place in digital art, which sparked frustration and criticism among competitors. Ragland hopes to continue appreciating real art, but as the line between AI creations and human creations becomes blurrier, that distinction grows increasingly difficult to make.

In addition to artistic integrity, Ragland expects that as AI improves, the film industry will begin cutting corners — and subsequently cutting jobs. “The film industry is already very much corrupted by money and interest,” Ragland said. He worries that AI will only worsen this corruption. Even without AI-generated video, many jobs in the film industry could potentially be replaced with AI: minor actors, sound designers, foreign language translators, and graphic designers are all at risk. This concern isn’t futuristic; two months ago, the horror film “Late Night With the Devil” received backlash for using AI to generate a few small graphics. While this film’s AI use was minor, it set a precedent for the film industry. As AI decreases the cost and time-consumption of filmmaking, Ragland’s expectations for the future of cinema grow bleaker. “People [in the film industry] want to support what makes them money rather than what has artistic merit,” he said. “AI in film would just further suppress artistic expression.”

Freshman Rex Hall isn’t just excited to use AI — he’s even begun coding his own. Hall, a coder, knows he should be apprehensive about AI taking his future job opportunities but instead finds himself excited about solving problems with it. He uses AI almost daily for programming and bug-fixing. Hall believes that AI is particularly good at writing and reading code. He often uses AI as his co-pilot when coding games, websites, and hobby projects. AI helps Hall approach coding projects that he wouldn’t be able to complete ordinarily. “I used AI to help me create [my website] by

having it write code that I didn’t know how to write and also to do some calculus,” Hall said.

Although Hall uses AI frequently, he isn’t blind to its flaws. When AI checks his code for bugs, Hall notices that sometimes, AI worsens the problem rather than fixing it, and he has to do even more work to fix the broken code. Even when AI debugs his program, there are downsides. “[AI] will fix stuff, and it won’t tell you how,” Hall said. “You won’t know how to fix it in the future.” Still, he finds that using AI to help him code is worthwhile because it helps him approach difficult programming tasks and complete more of his passion projects.

Hall knows that AI can program, but he doesn’t expect AI to replace programmers. Having seen firsthand the imperfections of AI, he knows that AI still has a long way to go. “I don’t think it’ll ever get to a point where it’s flawless,” he said. “Humans will always need to be there to monitor it.” Since AI knowledge is based on human knowledge, Hall expects humans to play a significant role in its development and implementation. By embracing AI in coding, Hall is trying to secure his place in AI’s future. “Humans will always be needed, at least a little bit,” he said. “So I hope I’m one of those humans.”

Freshman Sage Schulte wants to write her heart out but fears AI will take her heart out of writing before she gets the opportunity. Schulte enjoys journaling about her own experiences to process her thoughts and hopes to make a career out of creative writing in the future. For her, writing is a cathartic way to share her own unique experiences. Schulte believes that generative AI threatens her artistic expression and her job prospects because it can write without that same kind of expression. “To me, writing is an outlet for all of my feelings,” Schulte said. “That’s not something AI has.”

As a freshman, Schulte is especially concerned with the rapidly dwindling job market for writers. She worries that AI development will develop dramatically before she can write. “By the time I’m old enough to pursue screenwriting or novel writing, AI will be advanced enough that those careers will be way harder to get into,” Schulte said. She believes that although all arts jobs will be at risk because of AI-generated art, writers will be hit the hardest. The speed and convenience of generative AI writing make it extremely effective, especially compared to human writers. But Schulte, despite her doubts, isn’t planning to give up on her writing dreams. “Even if AI makes [being a writer] harder, I would still do it, and I would still try to make a career doing it,” she said. “I just don’t know if I could be as successful.”

Despite her criticism and concern over AI writing, Schulte still acknowledges the helpfulness of AI in her daily life. She often uses AI to help explain math problems step-by-step and feels optimistic about scientific advancements made by AI. However, she draws the line at AI doing anything creative. “There is definitely good writing and bad writing, but it’s not like math,” she said. While AI can help explain the correct answer to her math homework, she doesn’t believe there’s one correct way to write. For her, the creator’s intent is the most important part of art. “AI takes away the humanity of writing and art in general,” Schulte said. “It takes away the emotions because AI doesn’t have emotions.”

Junior Indigo Morgenstern is on board with the future of AI and is ready for humanity to perform alongside it. She wants to go into science and is particularly excited about AI’s impact on research and development. While she has occasionally used generative AI like ChatGPT, she’s more excited about AI’s ability to break new ground in scientific fields. “AI has a great capacity to solve difficult problems and to save lives and improve lives,” Morgenstern said. In particular, Morgenstern is optimistic about AI making new developments in medical diagnoses and treatments. Her hope isn’t unfounded: AI has already begun predicting protein folding from amino acids, a problem human scientists have been stuck on for fifty years.

Morgenstern hopes to work with AI in the future, so she isn’t concerned about her own career prospects. However, she isn’t concerned about AI taking over other jobs, either. In fact, Morgenstern believes that the more work AI can take on, the better. “I think we should restructure our entire economy around technology rather than suppressing it,” she said. Morgenstern believes that as AI gets more efficient, society will need to change to accommodate it. She argues that instead of demanding more jobs, people should demand universal basic income and comprehensive unemployment support. “The problem is not the technology,” she said. “The problem is that the government isn’t providing for people who are unemployed.”

Despite her lofty hopes for the future, Morgenstern still doesn’t fully trust AI at present. Since AI platforms like ChatGPT rarely show their sources to users, Morgenstern doesn’t trust their results. She is hesitant to use AI as a search engine until she can ensure that the information she receives is reliable. Morgenstern has compromised by only using AI to clarify information she already knows. “I use [AI] to explain a subject that I have a basic knowledge of, and then I can verify it,” she said. While Morgenstern is excited to learn more about AI, she still has doubts about its current iteration, particularly its logical process. “We know how humans work,” she said. “AI is unpredictable by comparison.”

Senior Leo Needleman presents a contradiction: he is both excited and apprehensive about the future of AI. While he intends to pursue engineering, he also writes as a hobby. For him, AI is a double-edged sword. While it has huge potential to help engineers become more efficient, it also holds a knife to the throat of writers and artists. As someone who will have to face both sides, Needleman struggles to balance his feelings about AI’s rapid development.

Needleman’s hobbies include creative writing and playing music. Though both of these are at risk of being taken over by AI, he isn’t particularly concerned about the impact of AI on his own artistic experiences. “I don’t think I’d switch over to using AI for writing or music,” he said. “I get enjoyment from the act of doing it.” For Needleman, the joy of writing stories or performing music is the process, not the finished product. While AI can replicate art or music, it can’t replicate the creative process. Needleman doesn’t completely dismiss AI from creativity, though; he sometimes uses generative AI writing to help prompt his imagination. “AI gives me ideas, and I take those ideas and build off of them,” Needleman said. Instead of using AI-generated text as is, he often uses AI to help brainstorm ideas, and does the actual writing himself. This way, he gets maximum enjoyment from writing, and doesn’t allow AI to take away his creative outlet.

The key to maintaining a positive relationship with AI, Needleman says, is to ensure that AI is a tool for humans, not a replacement for them. Although AI could make some engineering jobs obsolete, Needleman remains excited about AI testing of engineering projects. Because AI can run through thousands of scenarios in an instant, it can test how devices respond to complex environments with minimal resources. AI testing could help his future work become safer and more efficient, allowing him to spend more time actually designing. Needleman isn’t sure whether he’s optimistic or pessimistic about the future of AI, but he believes that either way, AI development is inevitable. As such, he feels that the best approach is to confront AI development head-on and learn about it as much as possible. “I don’t want to say ‘curb the development of AI,’ because it has legitimate benefits that could be realized,” Needleman said. “We need to learn to work with AI instead of being replaced by it.”