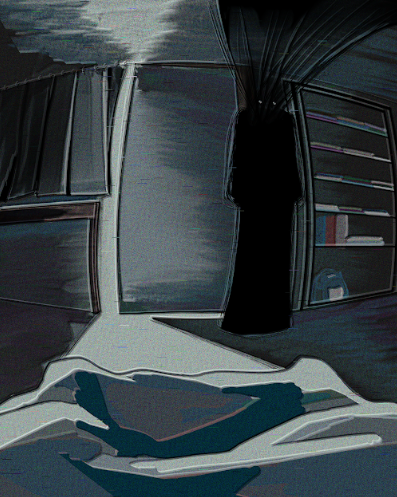

“You’re so quiet,” my mom’s friend said, her tone patronizing. I turned bright red. I was ten years old, and my family was hosting a holiday party. I emerged from my room to grab some snacks, hoping to avoid being noticed by the loud, chatty adults. However, one of my mom’s friends approached me, asking about school and what books I was reading. I spoke with mostly one-word answers, to which she went on to respond condescendingly. Embarrassed and confused, I quickly excused myself, trying to hold back tears as I sped back to my room.

In my experience, being introverted has been viewed as something to overcome, a flaw rather than an innate personality trait. Now, when distant family members or my parents’ friends tell me I’m more talkative than I used to be, they seem to wonder how I overcame this “obstacle.” Frankly, this offends me. I believe that being an introvert has its benefits.

Why does society consider introversion, a core part of my personality, a barrier and an impediment to my ability to succeed and lead others?

In general, American society views extroversion as the ideal personality type, assuming that assertiveness and charisma are traits vital to succeeding in school, the workplace, and inter- personal relationships. In a Wall Street Journal article, author and management professor Leah Thompson explains how these qualities that come naturally to extroverts make them “more likely to be chosen as leaders over their more introverted peers.” Because introverts are generally expected to modify or overpower their natural quietness to appeal to those around them, their leadership potential is often left unnoticed. As I’ve been conditioned by my surroundings to embrace extroversion as an indicator of “success,” I have found myself feeling out of place time and time again.

I know I am naturally introverted — I don’t feel the urge to speak for the purpose of filling in silence, nor do I think outwardly when problem-solving. Because of this, I believe there are more opportunities for observation and, subsequently, understanding. When I quietly observe, my awareness of the world and the people around me becomes clearer. I set aside my own perceptions and beliefs, taking note of what’s going on around me. I’m also able to engage in introspection by reflecting on myself, my beliefs, and my values. Especially after large social gatherings, as I “recharge,” my creativity and willingness to look inward flourishes.

Just because I’m introverted doesn’t mean I’m unable to put myself out there, but it means I think before I do. According to a study by the Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, introverts’ tendency to reflect before acting aids with problem-solving and creativity, which I find to be true in my life. When I participated in a policy-related youth leadership program, I collaborated with a team of other high schoolers in designing a group project to create a positive social impact on the community. Through many team brainstorming sessions, I made sure to sit back and actively listen, taking note of others’ ideas and providing feedback to my peers. Through internal reflection and my observation of others’ ideas, I proposed hosting a presentation regarding San Francisco’s homelessness. My idea pulled the team to a consensus, where we refined and executed this project as a team. By laying back and observing the conversations we had, I was able to intervene eventually to steer the group toward success. Although I was quiet at first, I used that time to fully reflect on my own ideas, as well as others’ ideas to influence the group effectively.

Over time, I’ve learned to step out of my comfort zone to succeed both academically and socially. I recognize there’s a fine line between stepping out of your comfort zone and modifying your personality altogether. So, I don’t force myself to be outgoing or charismatic constantly because, frankly, trying to do that is exhausting. In the same vein, I’ve exerted my energy into taking on leadership roles as a means of stepping out of my comfort bubble, not changing my values. From leading projects to help the homeless to presiding over Lowell’s literary magazine, The Junkyard, I’ve maintained pride in my introversion.

While hearing others point out how quiet I am used to irk me, I now take it into stride — being introverted is a trait that I’ve reckoned with and shouldn’t be something that’s antagonized. For most of my high school experience, I constantly wondered why I couldn’t summon up the courage to actively participate in class or be outgoing in social settings, but I’ve come to the realization that being an introvert is something I should embrace, not change. I’ve learned that whether someone is introverted or extroverted — or somewhere in between — is just a single part of how we interact with the world. Recognizing that I don’t have to conform to the socially praised world of extroverts has allowed me to navigate high school authentically and confidently.