Cantonese should be taught at Lowell

In the dimmed hospital corridors, I was translating my tongue off. Nobody in the hospital could translate what the English-speaking doctors were saying to my Cantonese-speaking mom – no one except for me. So, we had to make do with my subpar Cantonese. My hands frantically moved in gestures to help make my awkward tones and occasional English phrases easier to understand. As the conversation wrapped up, I felt like a marathon runner, dry-mouthed and dazed. Suddenly, my ability to help my mom communicate felt inadequate.

This realization terrified me. If I couldn’t speak fluent Cantonese anymore, how would I be able to communicate effectively with my family?

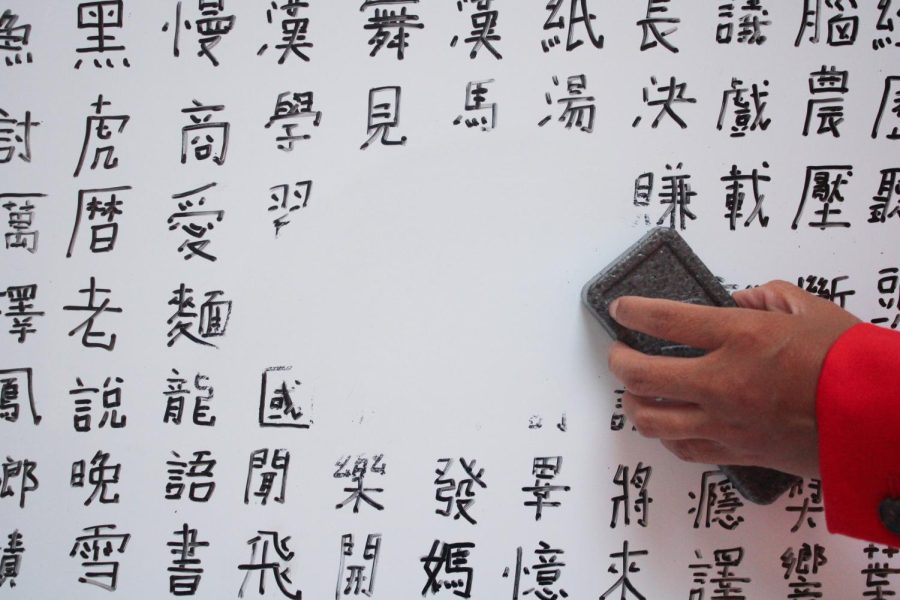

Cantonese is a dialect spoken in southeastern China, primarily in the Guangdong province, which is where most Chinese people emigrated from before 1960. Historically, San Francisco has had a large Cantonese-speaking population due to its status as a port city, which made it a popular spot for immigrants to settle. This population is evident in the Language Access Ordinance’s 2021-22 report, which states that Cantonese was the second most used language in interactions with city departments in San Francisco, making up 31 percent. In an informal survey of a Chinese 2 class at Lowell, 77 percent of respondents spoke a Chinese language other than Mandarin at home, 80 percent of whom spoke Cantonese. Despite this, Cantonese is not one of the seven languages taught at Lowell.

However, another Chinese language, Mandarin, is taught here. Why? Mandarin’s status as the People’s Republic of China’s national language is the main reason why it is more commonly taught. Additionally, China’s political and economic rise on the world stage within the last decade has made Mandarin more valuable to learn. But if you’ve ever stepped foot in San Francisco’s Chinatown, you would know how much Cantonese dominates that neighborhood. Store signs are written in the traditional script (Mandarin usually favors the simplified version), and some shopkeepers speak the language exclusively. Could someone learning Chinese through high school classes in the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) even apply what they know in their immediate surroundings? Not really. Although Mandarin is a useful language to know, Cantonese has a unique place in San Francisco and should be a language taught within the school district.

Upon entering Lowell, I didn’t realize the drawbacks of learning only Mandarin in school. Initially, I reasoned that it and Cantonese couldn’t be that different. I was wrong. Cantonese and Mandarin are both considered a part of the Chinese language family — an umbrella term used to describe the languages spoken in China — but are in practice almost unintelligible from one another. Everything from tones to grammar is different, with only the writing system being something they share. Mandarin was so similar yet so different from Cantonese, which led me to confuse words and mispronounce tones. I quickly realized that learning Mandarin was not helping when it came to communicating with my family. I’d find myself thinking in both languages when speaking with my parents. Exclusively knowing words in one language and other words in another made it awkward and confusing to have conversations. So I ended up having to learn an entirely new language instead of building upon the one I already knew. Now I’m shallowly fluent in both dialects and am nowhere near achieving the biliteracy I hoped for.

SFUSD provides no resources for learning the Cantonese language in a formal class setting for high school students. A look at the district’s website shows resources for both Cantonese and Mandarin. But the only resources provided for Cantonese are immersion programs in certain schools, most of which are on a preschool and elementary level, with only a few middle schools continuing the program past that.

The only other option SFUSD high schoolers have are the Cantonese classes offered at City College. However, San Francisco’s community college only has one full-time Cantonese instructor who teaches two classes per semester. According to KQED, both classes are filled with essential workers, and the waiting lists for these classes are long. This makes it difficult for high schoolers to take Cantonese there.

The lack of Cantonese instruction has negatively affected me. I grew up speaking Cantonese as a first language but slowly lost my fluency when I entered elementary school. My elementary school didn’t have an immersion program, leading me to speak Cantonese less often and slowly lose vocabulary. As a result, I became more alienated from my family, neither side being able to truly understand one another. The more this went on, the more desperate I became. However, I was met with a lack of resources and accessibility.

The role of Cantonese in San Francisco is important for residents of the city. But due to a lack of resources and accessibility, it’s getting harder to learn a language that connects many with their families. SFUSD does little to alleviate this and effectively nothing for Lowell students. Taking Mandarin has left me confused and just as lost as I was before. This is why the district should provide Cantonese resources to high school students. Learning this language would allow them to connect with their family and culture, as well as continue a unique San Franciscan tradition.

Charon is an illustrator in their senior year. They are non-binary and use they/them pronouns. Usually just a homebody with a love of the post-apocalypse and wild west genres. As well as an eye for collecting charms, pins, patches, and other knick-knacks. Currently hemiplegic and recovering from a stroke.

Katharine is a senior at Lowell. Outside of school, she can usually be found watching a film at Balboa, jamming to The Cure, or chasing her cats around the house.

Dennis Leong • May 27, 2023 at 5:49 pm

I can relate with your experience. This was back in the 1960s and 70s. I graduated from Lowell in 1966. At that time Chinese San Franciscans mainly spoke Cantonese. Last time I was in Chinatown about 6 years ago, it was no longer recognizable (except for the buildings). People there spoke many Asian languages and few spoke Cantonese. My mother spoke mainly a Cantonese dialect – Toishan. I usually had to act translator. It was difficult. I worked at UC. Berkeley and I took a few Mandarin classes at the extension. It actually helped with my Cantonese. My parents have passed, I’ve retired and moved to Texas. I rarely now speak Cantonese (Toishan). I lived out in the Richmond district before I got married but always had family there. I always had connections there before moving to Texas and it also changed. Clement Street had already become more diverse and many other Asian businesses moved in. I don’t know the Lowell demographics now but I would think the Asian students there are just as diverse as the City. I think in the long run a Mandarin class is more important and useful. Just my two cents. Good luck.

Vince King • May 26, 2023 at 8:40 am

I think my sister used to take Cantonese at church in Chinatown when we were younger. There are options for people who really want to learn Cantonese, rather than ask an overburdened school district to fund more classes.

I find it interesting (and sad) that you state that you grew up speaking Cantonese as a first language but lost fluency as you entered elementary school, especially if your mother only speaks Cantonese. Did you just stop communicating with your mother? How did this happen?

Most bilingual kids I knew in high school spoke Cantonese at home and English at school, so they maintained fluency in both. It seems that your loss of fluency in Cantonese was more from choice, rather than lack of resources.

Here’s an idea – start a student club. Ask your fluent Cantonese-speaking friends to teach you Cantonese and help you practice.

Albert Wong • Jun 6, 2023 at 7:31 am

“Did you just stop communicating with your mother? How did this happen?”

That’s rather judgmental and extremely uninformed. Nearly every bilingual kids start losing fluency in their first language after entering school because the language exposure changes so much. This is so well known I’m really confused at how the previous comment could be written — especially if someone has grown up around other kids who are bilingual.

Even when the kids do retain heritage languages, the language fluency is limited to household discussion. You’d never learn how to discuss most things beyond “get me a fork”. This is especially true of languages like Cantonese where written form (aka book form) is significantly different in grammar and noun usage. You’ll find many bilingual heritage cantonese speakers would not be able to decode a news broadcast.

This is also why having fluent friends “teach” you and practice doesn’t work enough. That is helpful, but not sufficient. I mean, when are you friends going to help you with fluency on how to greet folks at a wedding?

I know all this because I did what you were suggesting growing up. It does not work. I was fluent. I lost a lot in elementary school. I started speaking Chinese exclusively to my mom. It stopped working eventually as topics got to complex for me, and also for them as the decades went. I had to get formal instruction to progress further.

Even if you don’t want to advance fluency that far, you also basically cut out folks with mixed linguistic heritage. If someone is of a nuclear family that is predominantly english/mandarin/other they may lose the initial heritage tongue of their first primary care giver…which may cut out half the family.

Whether or not it’s worth having the school system teach it is a different and reasonable question.

However suggesting that somehow a person is at fault for losing their first language after entering school where the majority of all linguistic interaction turns to English is incorrect shaming.

It belies extreme ignorance and exacerbates a lot of “younger generation linguistic shaming” that needs to be called out.