My silent protest

As the teachers finished organizing us into our class lines, everyone quieted down for the morning assembly. Our necks straining to watch the cues of the lead drummer, we began proudly harmonizing to the Tibetan national anthem. But as I was singing along, a flash went off from the corner of my eye. Suddenly, the loud beats of the drum became a faint background noise as the pounding of my heart took over. I slowly turned my face away from the camera, as I began to feel my hands shake uncontrollably.

Although this was a typical Sunday school morning assembly routine, my fear of being photographed while participating prevented me from singing along.

Growing up, I often heard stories of people inside Tibet being punished for the political involvement of their relatives abroad. Because I have close relatives that live there, I began restraining myself from participating in certain Tibet-related activities, such as the annual uprising protests and religious community events. The only methods of protesting I could participate in felt ineffective, as they were always silent and non-political. But as I grew older and my view of the world expanded, I realized that by just keeping my language and culture alive, I was positively contributing to the greater Tibetan struggle. Although I initially felt purposeless in the Tibetan movement, I eventually learned that I didn’t need to protest in public in order to make a difference. Instead, I realized that there was value in keeping the non-political aspect of my Tibetan identity alive.

To fully assess the scope of the Tibetan-Chinese conflict, you must understand the historical relationship between these two neighboring nations. Although the Tibetan empire dates back to prehistoric times, its invasion by the People’s Republic of China in 1949 resulted in the loss of its independent status. As the Tibetan people do not recognize the Chinese government’s legitimacy in Tibet, numerous uprising and coup attempts have been made. Consequently, Beijing strictly controls this region, heavily cracking down on any form of protest and cautiously monitoring its internet for signs of resistance.

If I were to be publicly politically involved in the Tibetan-Chinese conflict, my family in Tibet would face unjust suspicion by the Chinese government. Actions such as participating in protests calling for the independence of Tibet or showing respect to the Dalai Lama (Tibet’s spiritual leader) could cause my relatives inside Tibet significant trouble. These relatives, which include my aunt and her family, could be put under constant scrutiny from officials. If incriminated, they could lose their jobs, homes, and even their children. So when I realized that the photo of me singing the Tibetan national anthem could be used as a weapon to attack my aunt and cousins, I feared for the safety of my family in Tibet.

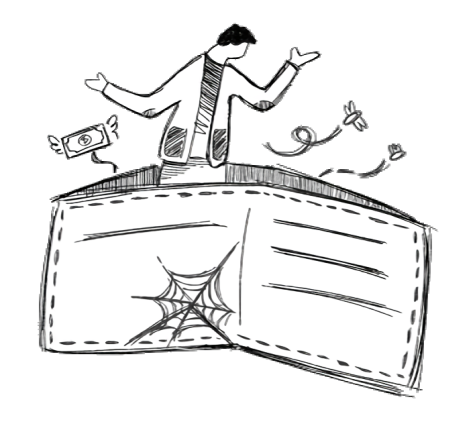

My parents and I have always resisted the Chinese government in a more private manner. Even as Americans, we can’t attend independence rallies or join any Tibetan organizations in fear for our relatives in Tibet. Instead, we’ve studied our language and preserved our culture as much as possible. Although this has no major or immediate political effect, it is a silent protest of the Chinese assimilation of the Tibetan people and culture. But for as long as I can remember, I have been self censoring my words, thoughts, and actions.

Because I have always been aware of the consequences my aunt’s family could face in Tibet for my actions, I have kept myself isolated from political events. In addition to having never participated in an independence rally nor being present at any heavily politicized event, I have even stopped myself from going to community concerts because of the highly political hosts. Recently, I became exhaustively aware of how much I was restraining my words and actions when I rejected a friend’s invitation to attend Tibet Lobby Day. Tibet Lobby Day is an annual three day event hosted by the Students for a Free Tibet organization. Tibetan Americans from multiple states went to Washington D.C. and talked state representatives into supporting the Tibetan cause. As well as being a great opportunity to connect with senators and representatives to push for Tibet related bills, it was also a rare chance to network with young Tibetan American students and professionals that live across the country. As I watched daily updates of the lobbying event through social media, knowing that I couldn’t participate because of the jeopardy it might’ve put my aunt’s family in, I felt completely useless and isolated from the greater Tibetan struggle.

However, as I began to notice increased methods of silent protesting in recent years, my initial rejection of this technique’s effectiveness was altered greatly. Last fall, an apartment fire in Xinjiang resulted in the death of 10 residents. Because of zero-Covid policies in place, firefighters at the scene were not allowed to interfere with the disaster, sparking mass protests across China. To counter relentless online censorship, citizens of major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Chengdu resorted to several days of blank paper protests. Instead of signs with political slogans, protestors held up blank sheets of white paper, symbolizing the lack of freedom of speech in China. These pieces of paper represented the Chinese people’s criticisms to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that they could not safely vocalize. As I realized this sentiment, I was reminded of the ways that I couldn’t speak up for myself and my country. I began to understand that my silent struggle against the CCP was not an isolated one. Across several countries, Chinese citizens showed up to protests with covered faces and blank paper. They understood the risk of vocalizing their dissent, and still had shown up in a literal silent protest.

The Tibetan youth inside Tibet had also found a solution. Right around the time of the blank paper protests, I participated in a non-political engagement conference bridging the gap between the Tibetan youth inside Tibet to those abroad. Here, I was introduced to several community-based projects that Tibetan youth were involved in. Although it was never directly stated, many of these projects were methods of silent protest. For example, a group of students had created a Lhasa (Tibet’s capital) map initiative. Although on the surface, it just seemed like a map project that recorded Lhasa’s layout, it was, in reality, one of the only ways to save the parts of cultural architecture that had increasingly continued to disappear as the Chinese tightened their grip on Tibet. The Lhasa map initiative created three dimensional models of the ancient city’s layout, accompanied by videos explaining the historical and cultural significance behind each of the roads, buildings, and religious structures such as temples. Additionally, I was introduced to the concept of Tibetan hip hop, which used music to keep hold of one’s identity. The underlying message in Tibetan hip hop was to tell the Tibetan youth to be proud of their language, culture, and identity. Through the universal language of music, this message continues to resonate well with the Tibetan youth both in Tibet, China, and abroad.

Gathering inspiration from the Chinese citizens and the Tibetan youth inside Tibet, I have focused my attention onto my own ways of silent protesting. Through my cultural interests in the ancient linguistic system to the extensive medicinal and psychological practices, I began working to keep these elements of our culture alive. I intend to document and translate these aspects of our culture into the English language so that the next generation of Tibetan-Americans can easily access them, even if a language gap occurs.

Censoring myself as an American has always been something I despised of my Tibetan background. Nonetheless, my recent observations and experiences of the silent resistance methods used by Chinese and Tibetan people have comforted and inspired me. It has always been a challenge to quietly resist, but now that I know that I’m not alone, I see this as an opportunity, rather than a challenge. Like the Chinese protestors who used blank pieces of paper and the Tibetan youth who use rap to keep their identity alive, it is now my turn to discover where I fit in as a silent but hopeful fighter.