A culture of comparison

Gym culture has risen in popularity among teenage boys, leading to an obsession with muscularity and body image issues.

Senior Caleb Leung walks out of the gym tired yet satisfied, having lifted a new milestone weight, one he couldn’t have imagined lifting just a month or two ago. As Leung opens TikTok to post his new personal record, he sees a video of another man lifting an unbelievable amount of weight. Impressed, he scrolls through the other man’s profile, seeing months and months of progress condensed into just a few videos. He frowns as he puts his phone away, excitement over his new personal record erased. Leung contemplates whether he should do one more set, each passing second feeling like wasted time.

Going to the gym is a hobby rising in popularity among teens, especially teenage boys. While going to the gym yields many physical and mental health-related benefits, one of its potential negative consequences is body dysmorphia, a mental condition that involves an unhealthy perception of one’s body. Body dysmorphia is primarily associated with females, accentuated through pop culture and unrealistically high beauty standards. However, body dysmorphia affects males as well, often leading to similar behaviors like restrictions on diet and low self-esteem. Whereas girls suffering from this condition usually fixate on thinness and see themselves as overweight, boys are most likely to focus on adding muscle mass and see themselves as overly thin. As a result, the term muscle dysmorphia is often ascribed to males suffering from this condition. Social media has created an additional outlet for gym culture to idealize muscularity and put pressure on boys to obsess over working out and bulking up.

Body image has been stereotyped as a female issue, causing it to be overlooked in men despite it being prominent among males. According to Dr. Jason Nagata, a pediatrician at UCSF specializing in eating disorders, the lack of attention to body image issues has given boys more reason not to seek help or talk about it. “There’s already a stigma for anyone with body image issues or eating disorders regardless of their sex or gender,” he said. “But boys and men with muscle dysmorphia have a double stigma because they’re both affected by this condition and they are an underserved population. That is even harder for them to talk about.” Nagata pioneered the term “Bigorexia,” a nickname for muscle dysmorphia, which refers to the preoccupation with insufficient muscularity that can impede peoples’ ability to function. This may lead to anxiety, depression, or eating disorders. According to a 2019 study, around one-third of teenage boys are actively trying to gain muscle mass, with one-fourth changing their diet or using muscle-enhancing supplements to do so.

While many teens go to the gym to improve their body image, doing so results in the opposite for some individuals: further insecurity and increased body dysmorphia. Leung began going to the gym to get bigger muscles, feeling indirect pressure from peers and himself to meet his high standards. Although his overall perception of his body has improved since he started lifting, Leung feels like going to the gym intensifies pre-existing insecurities of thinness, largely due to impatience with muscle growth. “You go to the gym to improve yourself, but you don’t feel like you’re improving,” Leung said. “It’s a slow, long-term improvement, so when you go to the mirror the next day expecting to see something, you don’t see it right away.” According to Leung, this is what leads to the obsession to achieve muscularity and bulk, his definition of “perfect body,” and leads to “feeling like [you’re] not good enough for other people, and for [yourself].” He even tells himself he isn’t good enough to find a source of motivation to lift. “I put myself down on purpose and make myself want to go to the gym and work out even harder,” he said.

Many boys become obsessed with going to the gym. According to Nagata, some teens may become overly dependent on the gym, specifically those who experience body dysmorphia. “People who develop body dysmorphia feel guilty if they’re not exercising all the time, and it becomes an obsession,” Nagata said. To see serious results, Leung began overly dedicating his time to the gym; he changed his diet and began spending all of his free time working out. Leung believes there’s a healthy extent to that, but it can also go too far. “If you don’t have self-discipline, you get lost going to the gym,” Leung said. “You’re going to focus on the gym, which becomes your life, and you don’t have a life anymore.” This summer, he fell into the hole of weighing food and obsessing over calories, not letting himself enjoy anything else. He stopped going out with friends and found himself going through the same daily cycle: gym, home, sleep and repeat. For Leung, being unable to go to the gym reminds him that people are working while he isn’t, which manifests in a feeling of being undisciplined. “I feel disappointed whenever I miss a day,” Leung said. “I feel like I’m going to lose all my progress in that one day.” Senior Zameer Maqsood’s routine is dependent on the gym, as it adds structure to his day. “Without that structure, everything falls apart,” Maqsood said.

Body dysmorphia often causes disordered eating that can have extreme health consequences. Dr. Nagata works with patients who can’t eat out at restaurants or with their families because they can’t reach their nutrition goals. “It really leads to impairment in the quality of one’s life,” Nagata said. According to him, people with body dysmorphia don’t often get enough nutrients to sustain their exercise habits; if they’re not eating enough and are in the gym for hours every day, they can get seriously sick and end up in the hospital. According to Leung, his progress of muscle gain slowed down because he isn’t on a strict, high protein diet anymore. Although his past eating habits have improved, Leung still struggles to forgive himself after eating large amounts of unhealthy food, feeling guilty and lazy if he doesn’t immediately burn off the calories. “If I eat five slices of pizza or something I… put myself down until I want to go to the gym again,” he said.

Body dysmorphia often causes disordered eating that can have extreme health consequences. Dr. Nagata works with patients who can’t eat out at restaurants or with their families because they can’t reach their nutrition goals. “It really leads to impairment in the quality of one’s life,” Nagata said. According to him, people with body dysmorphia don’t often get enough nutrients to sustain their exercise habits; if they’re not eating enough and are in the gym for hours every day, they can get seriously sick and end up in the hospital. According to Leung, his progress of muscle gain slowed down because he isn’t on a strict, high protein diet anymore. Although his past eating habits have improved, Leung still struggles to forgive himself after eating large amounts of unhealthy food, feeling guilty and lazy if he doesn’t immediately burn off the calories. “If I eat five slices of pizza or something I… put myself down until I want to go to the gym again,” he said.

With the accessibility and algorithms of social media, boys are constantly being exposed to content created by men and other teens with extreme muscularity. Junior Parker Higgins is used to seeing gym-related content; people posing, lifting, and even giving advice remind him that there are people who have made more progress than him. “If I’m scrolling on Instagram and I see all these jacked dudes who look better than me, it makes me self-conscious,” he said. “So there’s a constant hunger to get better at weightlifting and go to the gym.” Nagata explained how social media algorithms create a negative feedback loop, where engaging in gym-related content on social media leads to it consuming your entire feed, further promoting muscularity issues and driving interest higher. This follows a trend noticed by Nagata and other professionals, where teenagers who engage on social media are more likely to be dissatisfied with their bodies.

Not only does social media target viewers with specific content, but it also tends to portray working out through a positive and desirable lens. Leung noticed how social media creates an illusion of noticeable gym progress happening quickly. “With social media, you go into a TikTok page, and you see a whole year of progress,” Leung said. “But you scroll through it in five minutes, making it feel like that progress only took five minutes to get there.” Although not an avid gym-goer, Senior Alex Blacker has also noticed the false narrative social media creates around gym progress. According to him, while some content has valuable aspects, much of it pushes people toward unhealthy gym habits. “Especially on Instagram, there are things like, ‘You’re working out wrong. This is how you get six-pack abs,’” Blacker said. Blacker agrees with Leung on the harm of seeing years of progress condensed into a short clip or just a few posts. “People might think, I’m not gonna have to work out for that long. I just have to work harder, and so they’re gonna push themselves too far,” Blacker said.

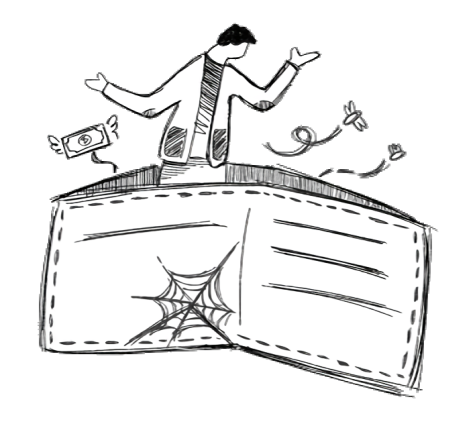

Even for people who don’t go to the gym, not working out can cause insecurities around their body image by being exposed to aspects of gym culture through their friends and social media. Senior Dexter Shen doesn’t go to the gym, but is surrounded by friends and peers focused on improving their physique, which makes him feel pressured to do the same. Shen thinks there is an ideal body, and more importantly, he doesn’t have it. This becomes a barrier for him in both his mental health and personal life. Within hookup culture, Shen believes that having a “good” body is essential, causing him to feel unattractive and uncomfortable with showing his body when with a partner. “I’m just not appealing if I’m not fit,” he said. In addition to body image issues, Blacker views the gym as creating a toxic culture that equates body image to self-worth. “I feel like part of [going to the gym] has become nothing but a comparison between yourself and other people,” Blacker said. “It’s almost like the weights are just values, and how much you can lift translates to your value.”

As an often normalized issue —that is, working out is good for you — solutions to male body dysmorphia can be harder to find without support. According to Nagata, the first step in dealing with body dysmorphia is to look for warning signs, from obsessions with weight gain or loss to excessive gym commitment; many teens who struggle with muscle dysmorphia don’t even realize it. Nagata stresses that reaching out to trusted adults and supportive friends about any concerns is essential. Leung, who experienced a period of over-commitment to the gym, says it’s hard to snap out of that cycle. “You can try to fix your own mindset, but it’s hard to do because it’s hard to see yourself doing something wrong,” Leung said. “From a first-person perspective, you don’t see it as that big of an issue, but once you step back and see it from a third-person perspective, you realize that it isn’t the best lifestyle.”

As an often normalized issue —that is, working out is good for you — solutions to male body dysmorphia can be harder to find without support. According to Nagata, the first step in dealing with body dysmorphia is to look for warning signs, from obsessions with weight gain or loss to excessive gym commitment; many teens who struggle with muscle dysmorphia don’t even realize it. Nagata stresses that reaching out to trusted adults and supportive friends about any concerns is essential. Leung, who experienced a period of over-commitment to the gym, says it’s hard to snap out of that cycle. “You can try to fix your own mindset, but it’s hard to do because it’s hard to see yourself doing something wrong,” Leung said. “From a first-person perspective, you don’t see it as that big of an issue, but once you step back and see it from a third-person perspective, you realize that it isn’t the best lifestyle.”

Although Leung and Higgins have recognized their experiences with body dysmorphia, they have found support from within the gym community, specifically from others who have gone through similar body image issues. Higgins believes that a common goal of self-improvement can unite the community and foster better mindsets that can counter insecurities, especially concerning body image. “You’ll see huge bodybuilders, skinny guys, and overweight people who have similar goals of getting healthier and having better habits,” Higgins said. According to Leung, receiving encouragement from adults and friends is the healthiest way to deal with dysmorphic conditions. “If you surround yourself with the right people who support you, you’ll eventually be okay with who you are and not get too deep into feeling like you aren’t good enough,” Leung said.

While gym-goers have found a positive community at the gym with peers who support them and push them to reach their goals. Some of Higgins and Leung’s favorite things about the gym are the people and atmosphere. For Leung, going to the gym allowed him to decompress and relax after school and from everyday social pressures. Higgins agrees, stressing that in some cases, gym goers are looked down upon for nothing more than participating in a hobby, something that people enjoy and use to help relieve stress. Higgins disagrees with stereotypes that gym-goers are self-obsessed and says they’re just motivated. “You shouldn’t judge someone’s personality off what they choose to do because they could have body image issues and stuff like that,” Higgins said. “People outside of gym culture view it as a bad thing, but it’s really just people trying to improve themselves. Everyone has their own way to do it.”

The gym has also positively impacted how some people go about their everyday lives. Maqsood’s self-confidence has steadily increased since he started going to the gym. He loves the way it helps him create goals, which has transferred to a better mentality of achieving goals in school and for his mental health as well. “In terms of mental health or personal goals, [it] can be hard to actually see the progress happening,” Maqsood said. “[In the gym], you can actually see progress over time. It’s been helpful to keep me going forward with goals because you can see progress.” Leung agrees with Maqsood, explaining that the ability to see progress both in his appearance and his strength makes him feel good as it shows him that the work he has put in has paid off. “[The gym] makes me work harder to get my goals because I know if I don’t work hard, it’s gonna take me longer to get there,” Leung said, “And that’s translated to like other parts of my life like school and work.

While body dysmorphia is a scarily common disorder among teenage boys who are familiar with or actively go to the gym, it serves as a platform to heal any mental stress from other parts of their life, as well as issues that going to the gym itself may cause. For Leung, while some aspects of the gym have caused additional stress on his body image, it has also improved his confidence and helped him grow as a person. “If you have a good mentality, the gym can only be good for you,” he said.

While the desire to improve initiates a strong drive to go to the gym, it may foster a debilitating feeling of insecurity when access to the gym is limited. According to Nagata, some teens may become overly dependent on the gym, specifically those who experience body dysmorphia. “People who develop body dysmorphia feel guilty if they’re not exercising all the time, and it becomes an obsession,” Nagata said. For Leung, being unable to go to the gym reminds him that people are working while he isn’t, which manifests in a feeling of being undisciplined. While this fosters an increased drive to work out, it reinforces signs of body dysmorphia, making him feel weak and insignificant. “I feel disappointed whenever I miss a day,” Leung said. “I feel like I’m going to lose all my progress in that one day.” Senior Zameer Maqsood’s routine is dependent on the gym, as it adds structure to his day. “Without that structure,” Maqsood said, “everything falls apart,” Maqsood explained how going to the gym as a part of his routine began affecting his body image; the quality of his body image became reliant on his ability to go to the gym — when his ability to go to the gym is hindered, he finds himself disliking his body more. According to Nagata, this only intensifies negative perspectives on individual body image, causing teens to grow more self-conscious and further their obsession with going to the gym.

Roman is a senior who, if not chugging coffee or blasting music, is only doing one of four things: playing baseball, watching the sunset, getting hit in the head with a bowling ball, or falling asleep at the dinner table.

Niyati is a senior at Lowell High School. In her free time, she works at the farmers market and walks around the city listening to music. In the words of fellow reporter Clarabelle Fields, she is described as enigmatic and magnanimous.

Charon is an illustrator in their senior year. They are non-binary and use they/them pronouns. Usually just a homebody with a love of the post-apocalypse and wild west genres. As well as an eye for collecting charms, pins, patches, and other knick-knacks. Currently hemiplegic and recovering from a stroke.

You can usually find Dary blasting music in her airpods and speed walking around in outfits she spent too much time thinking about, or that embodies the Adam Sandler within her. She loves to chat, so feel free to say hi or ask for help!