Guilty by association

The negative attention alleged assaulters received unfairly shifted to teammates and supporters of sports teams. A baseball player and cheerleader share their experience of alienation.

By Roman Fong

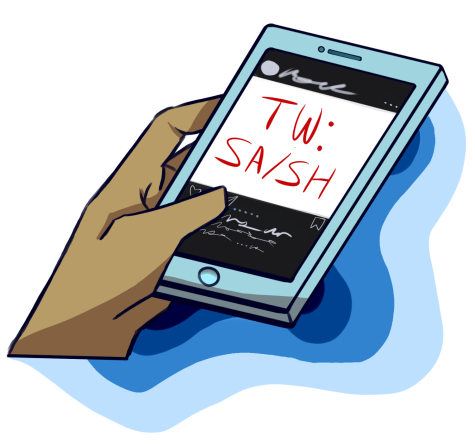

“TW: SA/SH.” I stared at my phone, confused, trying to figure out what those letters could mean. They had been typed in bright red above a post — the same post I’d seen reshared on numerous Instagram stories throughout the day. I tapped on the screen and began reading.

Little did I know my experience as a student athlete, specifically as a member of the baseball team, was about to change forever.

During October 2021 and the weeks following, many Instagram posts were shared, all reposted with the letters “TW: SA/SH,” which I would learn stood for “trigger warning: sexual assault/sexual harassment.” People came forward with their experiences around sexual assault and harassment, calling out not only abusers for their actions but the administration for doing little to alleviate the situation. Initially, the anger was mainly directed at perpetrators and admin, however, entire sports teams also began to receive backlash on social media. It seemed like the new negative attitude toward sports teams had taken away from addressing the real issue of dealing with sexual violence and created a new one — one where being on a sports team meant you were accountable for the actions of your teammates.

Initially tame, accusations and hostility against Lowell athletes increased. I saw reposts every day, telling us we were just as guilty as the perpetrators, urging us to quit the team to show solidarity with survivors. As a result, I stayed off social media, slamming my phone down every time I saw a notification, praying it wasn’t about a new post.

Avoiding social media seemed to work — until the issue caught up with me personally. “F*ck you! F*ck the baseball team!” someone said to me in the stairway. Out of nowhere, the gravity of the situation crashed in on me. I’d always worn my Lowell baseball cap and shirt around school with pride, but now doing so made me a target of hatred. The issue had become so much more than just sexual assault and harassment: The reposts and calls to support survivors had shifted from demands for awareness and action into a movement against sports teams.

The hostility towards sports teams didn’t relax for weeks. Athletes who’d done nothing but be on a team with the accused perpetrators were now being held accountable for someone else’s actions. Every new student’s Instagram story hurt more now that I was seen as someone who was a contributor to survivors’ pain. These were experiences that needed to be shared and people who needed to be listened to, but the more exposure the posts got, the more unnecessary hate sports teams received.

These extreme attitudes also take away from the principal purpose of sports teams themselves — for athletes to find enjoyment in a shared passion. Last year’s events changed how many, if not most, Lowell students perceive some of the school’s sports teams. These students have a negative association with boys’ basketball, football, and baseball teams in particular. I believe a distinction between athletes on teams and sexual assault must be made. People join sports as a way to form connections through a shared interest. Though it is crucial to acknowledge problems related to your team when they arise, athletes shouldn’t be seen as responsible for issues caused by a teammate.

I didn’t know how to react when I learned about the terrible things some people within my community had done, but it crushed me when whole teams, me included, were antagonized and put in the same boat as those perpetrators. Sexual assault and harassment awareness are topics that need to be taken seriously, but spreading awareness and calling for action shouldn’t create a new conflict and take away from what’s really important.

By Sierra Sun

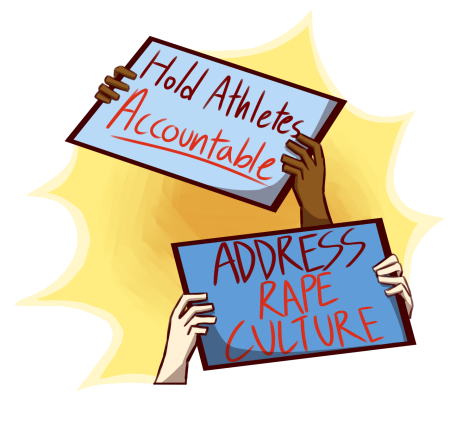

With red and white poms stuffed in bags slung across our shoulders, my teammates and I trot across the brightly lit court. Exiting Kezar stadium together, we were caught off guard by a crowd of students lined up holding large posters with bold red-lettered statements. The words urged more action to be taken against the athletes accused of sexual assault. Guilt washes over me as I realize that our cheering for the team, including the accused athletes, contradicts the beliefs of the protestors. I and the other cheerleaders quickly distanced ourselves from the crowd, not wanting to intensify the tension between protestors and the supporters of the event in our red uniforms and sparkly bows.

This was my experience cheering at last school year’s Spring 2022 basketball championship game.

Since the wave of sexual assault allegations against predominantly male athletes were reported to Lowell’s administration, uninvolved students have been unfairly blamed for the accused students’ actions. I and the many other students choosing to support these teams does not mean that we condone sexual assault or harassment at Lowell.

Unfortunately, sexual harassment remains a prevalent issue, especially on Lowell’s campus. I agree with so many frustrated students: the issue of sexual assault requires more attention from school administration in order to prevent future incidents. As a member of Cheer, it pains me to represent a school where sexual violence continues to be such a problem.

Though I enjoy yelling cheers to motivate my peers, attending school athletic events in support of sports teams has put me in an awkward situation. On the one hand, I feel obligated to uphold a positive image for my team. On the other hand, I feel reluctant to cheer for controversial athletic teams. I have felt alienated by students for showing support at games, where I am indirectly tied to teams consisting of alleged sexual assault perpetrators.

However, choosing to attend these sporting events should not make a person any less of an advocate against sexual harassment. For me, signing up to be a cheerleader implies my commitment to represent a positive image for the school and galvanize students, athletes or not. However, I also acknowledge that it means I am working with a historically feminine cheer team that upholds patriarchal gender norms; this includes the traditions of cheering for primarily male basketball and football games in skin-tight uniforms. Nevertheless, Lowell’s cheer program has made attempts to educate me and my peers through online USA Cheer safety curriculums, overviewing lessons on sexual harassment awareness. As I am fortunate to recieve exposure to the significance of these issues through the lessons provided to my team, my choice to continue cheering for sports does not correlate to condoning any part in sexual assault.

For general students that enjoy being present in the stands of Lowell sporting events, supporting their schools’ athletic teams is a way of spending their leisure time outside of a stressful academic environment. Attending these events helps students feel connected to their peers in the school community, and should not be seen as a means of antagonizing sexual assault victims. Since student-athletes have been villainized, supporters of sports teams have been attached to a negative connotation of sexual assault.

Having to wave my poms at the sidelines of boys’ sports games, I have felt hesitant to stand by teams consisting of athletes accused of sexual violence. The stigmatization of supporting athletic teams have unjustly grouped uninvolved students with the consequences of their peers. Though student organized protests targeting male sports teams for on campus sexual harassment have died down since last spring, the possibility of further rallying against Lowell’s athletes remains. In the event of student advocates deciding to march out of classrooms or holding up signs, it is important to consider the toll these demonstrations have on students like myself.

Roman is a senior who, if not chugging coffee or blasting music, is only doing one of four things: playing baseball, watching the sunset, getting hit in the head with a bowling ball, or falling asleep at the dinner table.

Sierra is a senior at Lowell. She loves munching on school lunch hotdogs and updating her secret Letterboxd account. Sierra also loves sunny weather.

Malena is a senior and a photographer for The Lowell. She loves listening to music, watching movies, and playing the guitar. Some of her favorite movies are The Sandlot, Up, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, and Blended

Charon is an illustrator in their senior year. They are non-binary and use they/them pronouns. Usually just a homebody with a love of the post-apocalypse and wild west genres. As well as an eye for collecting charms, pins, patches, and other knick-knacks. Currently hemiplegic and recovering from a stroke.