Demanding a difference

Students have spoken out against sexual violence on campus. How much of a difference has it made?

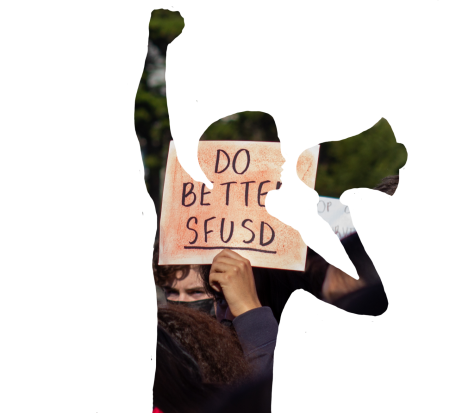

Senior Vianne Huynh stands on Lowell’s football field, stepping to the front of a crowd as a spotty microphone calls her name. A sea of students gathers before her, clad in red clothing. It’s been three days since she took to Instagram to inform the community that she is a survivor of sexual assault and reported her experiences to Lowell’s administration. Students have been uplifting the voices of survivors on social media and venting about the lack of support from administration in private. Now, they have walked out of their fourth period classes to publicly protest the lack of response to rape culture. Supporters and survivors at the walkout have made demands and recounted stories, and now it is her turn to speak. The posts and posters — the thank yous, I believe yous, and we support yous — strengthen her resolve as she faces the sea of students. They smile and they clap and they shout her name before they hush to hear her words. They listen. People start listening.

Posted in November of 2021, Huynh’s Instagram post was a small facet of a growing movement in support of survivors. Throughout the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), many students were inspired to share their stories of sexual assault and rape on social media. Social media was one of several platforms used to protest the cultural and adminstrative response to sexual assault. Because of this movement, more Lowellites found themselves seeking help from Lowell’s administration, but some survivors have expressed feeling unsupported at the end of the reporting process. Despite some cultural shifts and calls for more education on the subject, no written changes have been implemented into administrative or legal practices. As student protestors and supporters continue their advocacy for survivors, many are wondering: what methods of activism are actually making a difference?

The issue of sexual assault previously gained widespread attention in June of 2020, when dozens of students shared their stories with sexual violence on social media and demanded abuser accountability from the school as well as within social circles. In the fall of 2021, the movement spread from social media platforms to school campuses, as students at Ruth Asawa School of the Arts (SOTA) walked out of class to protest the handling of sexual assault at their school. On November 2, Lowell students organized a walkout to show solidarity for SOTA’s cause. A week later, student organizers held another Lowell-specific walkout to call out injustices within the reporting process at Lowell, publically support survivors of sexual assault, and provide a platform for survivors and supporters to give share personal experiences. By December 10, students from schools across the district joined forces in another walkout, this time to City Hall. A list of demands for SFUSD was written by organizers of the protest and distributed through pamphlets and speeches.

These walkouts did not go unnoticed by Lowell’s administration. According to Principal Joe Dominguez, the administration has prioritized clarifying the process for reporting incidents of sexual assault and harrassment since fall of 2021. Title IX coordinators are specifically trained administrators who carry out Title IX procedures, a law that protects students against discrimination and harassment based on sex, including sexual harassment. In August and September, one of Lowell’s Title IX co-coordinators, Kahlila Liverpool, had begun collaborating with students, department chair teachers, and other administration to define a three-step process for students to report disruptive incidents that had taken place on campus. According to Dominguez, administration immediately decided to share with students the reporting process that Liverpool had been refining after seeing the recent surge of activism.

Displays of public support spurred some survivors to report their experiences to the administration, but many felt unsatisfied with the logistics of processing their cases. Senior Rebecca Kang, a survivor who formally reported her abuser in Nov. 2021, felt unsupported by Lowell administration throughout the investigative process. Kang scheduled weekly meetings with Title IX co-coordinator Cheryl Fong in November to push her case forward. Finally, at the beginning of December, the administration told Kang that her case could no longer be considered because too much of her abuse had occurred off campus and they did not have the authority to take action against her abuser. However, according to Kang, at least four incidents of sexual assault that she reported had taken place at Lowell, with three occurring off campus, so she was surprised they would drop her case. “My report has the locations and times [of the event], and I wrote it with so much detail that multiple administrators even pointed it out and commended me…How was it not enough?” she said. “What more did they need?”

Huynh’s experience with reporting her assault to Lowell’s administration has been similar. She provided the administration with multiple pieces of evidence like text conversations that show her abuser harassing her and referring to events that happened on campus. But her case remains at a standstill. “It’s on campus, so they have to pay attention to this,” Huynh said. “I don’t know much about what’s going on and I still don’t know what’s going to happen, and it’s been a really long time.”

While some survivors like Huynh took initiative to report their abusers, others did not want to report but were pressured to do so. Emma, a Lowell senior who was interviewed under a pseudonym, never intended to report the assault she experienced her freshman year, but felt that administrators gave her no other choice. In November, she was called into Liverpool’s office and informed that her assaulter had made a statement, which she believes was prompted by a third party reporting her assaulter’s name. Liverpool told her that administrators needed a statement from her in order to proceed, or else they “wouldn’t know what to do.” According to Emma, very little has come of what she felt to be constant meetings with administration.

Emma feels that administrators risk misjudging the needs of survivors and harming their mental health as they pursue investigations. By repeatedly disrupting her daily life to discuss this traumatic event, Emma’s mental health and academic capacity became strained. She stayed home from school several times to avoid meetings about the investigation. Her psychiatrist ultimately wrote an email to inform Emma’s teachers and administrators that these meetings had reactivated her trauma. Asked to file a report against her wishes and attend meetings that hurt her emotional health, Emma felt the administration should have been more aware of her needs. “I don’t think that pressure should have been put on me,” Emma said.

Emma feels that administrators risk misjudging the needs of survivors and harming their mental health as they pursue investigations. By repeatedly disrupting her daily life to discuss this traumatic event, Emma’s mental health and academic capacity became strained. She stayed home from school several times to avoid meetings about the investigation. Her psychiatrist ultimately wrote an email to inform Emma’s teachers and administrators that these meetings had reactivated her trauma. Asked to file a report against her wishes and attend meetings that hurt her emotional health, Emma felt the administration should have been more aware of her needs. “I don’t think that pressure should have been put on me,” Emma said.

The administrators that currently carry out investigations and Title IX procedures are not always properly prepared to do so. When Emma made her report, she requested her family not be notified, which Liverpool told her would be respected. However, her parents were called in to speak with administration a few days later. After many meetings with Liverpool for her investigation, she met with Dominguez about the issue and told him that she had not wanted to report and that she actually felt pressured to do so. Dominguez apologized to her for this. While she was grateful for his understanding and desire to make things right, Emma believes the disconnect between Dominguez and Liverpool’s actions reveal conflicting procedures around investigations. Some administrators feel the same way. Fong says she did not feel that she was properly prepared to fulfill the role of Lowell’s Title IX Coordinator. People in the position receive yearly training through SFUSD’s Office of Equity, but she still felt thrown into the deep end while handling sensitive matters like sexual assault. “Unfortunately, it was a sort of learn-as-I-went-through-each-case situation,” she said.

Some of the limitations of the investigation process are due to laws, outside of Lowell administration’s control, that are in place to  protect all students, including those who are accused. According to Dominguez, the administration is often restricted from taking immediate action in response to abuse allegations by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects students’ privacy and rights to education. Dominguez wants students to understand that these laws are beyond him or other administrators’ control, and that FERPA can slow, limit, or completely block investigations. “While there might be a lot of feelings about what should happen to an individual, there’s this entitled right to a fair and free public education,” he said. According to Dominguez, to strip a student of their rights through a suspension or expulsion, administrators would need extensive proof that the abuse had occurred. Nuri Nusrat is a Restorative Justice Manager at Ahisma Collective, an organization that focuses on restorative justice and healing after traumatic events. Nusrat believes that school administrators are limited to a very small role when trying to obtain justice for survivors. “There are laws in place that require administrators to do specific things when hearing of an assault,” she said. “I think the only real thing an administrators can do is focus on prevention.” Despite restrictive laws, Liverpool wants to support survivors in any way possible. “We wish [that with] every single case that we interact with we could do something and fix it and make it right,” she said. “But unfortunately our hands are tied, in particular when it’s not within our jurisdiction as to what we can do.”

protect all students, including those who are accused. According to Dominguez, the administration is often restricted from taking immediate action in response to abuse allegations by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects students’ privacy and rights to education. Dominguez wants students to understand that these laws are beyond him or other administrators’ control, and that FERPA can slow, limit, or completely block investigations. “While there might be a lot of feelings about what should happen to an individual, there’s this entitled right to a fair and free public education,” he said. According to Dominguez, to strip a student of their rights through a suspension or expulsion, administrators would need extensive proof that the abuse had occurred. Nuri Nusrat is a Restorative Justice Manager at Ahisma Collective, an organization that focuses on restorative justice and healing after traumatic events. Nusrat believes that school administrators are limited to a very small role when trying to obtain justice for survivors. “There are laws in place that require administrators to do specific things when hearing of an assault,” she said. “I think the only real thing an administrators can do is focus on prevention.” Despite restrictive laws, Liverpool wants to support survivors in any way possible. “We wish [that with] every single case that we interact with we could do something and fix it and make it right,” she said. “But unfortunately our hands are tied, in particular when it’s not within our jurisdiction as to what we can do.”

The role of adults extends beyond the reporting process and into the broader prevention and proper handling of sexual violence at Lowell. Senior Rodrigo Flores quit Lowell’s varsity football team this past fall in response to the way the team dealt with sexual assault allegations against team members. Danny Chan, the coach of the football team, claims to have never heard of any allegations against this season’s players. “If they don’t say anything, I don’t know anything,” Chan said.

However, Flores did say something in November of 2021. Flores told Chan that he would be quitting the team because he felt uncomfortable playing alongside multiple players with sexual assault allegations. Chan informed Flores that despite the allegations, his football team had an open-door policy for joining and that everyone began the team with a clean slate. Flores felt that Chan’s response significantly downplayed the severity of the situation and overlooked the difficulty of being teammates with people who are accused of sexual assault. According to Chan, the character of his players is important, but as an off-campus coach, he doesn’t feel inclined to take any measures to control the actions of the players beyond the field without prior guidance from school administration. “If there is some kind of allegation, it would be nice for me to know,” he said. “But just like Elsa [of the Disney movie Frozen] said, ‘The past is in the past!’…I don’t know what these kids do, and again, they’re kids.”

However, Flores did say something in November of 2021. Flores told Chan that he would be quitting the team because he felt uncomfortable playing alongside multiple players with sexual assault allegations. Chan informed Flores that despite the allegations, his football team had an open-door policy for joining and that everyone began the team with a clean slate. Flores felt that Chan’s response significantly downplayed the severity of the situation and overlooked the difficulty of being teammates with people who are accused of sexual assault. According to Chan, the character of his players is important, but as an off-campus coach, he doesn’t feel inclined to take any measures to control the actions of the players beyond the field without prior guidance from school administration. “If there is some kind of allegation, it would be nice for me to know,” he said. “But just like Elsa [of the Disney movie Frozen] said, ‘The past is in the past!’…I don’t know what these kids do, and again, they’re kids.”

Among his teammates, Flores observed a culture of downplaying, joking about, and active disrespect of consent and women. “I didn’t want to be around that community,” he said. “I ultimately ended up quitting and not giving a second thought about it.”

Student activists feel that this culture of disregarding consent that Flores observed is beginning to shift as a result of the movement. Senior Reesa Tayag, a protest organizer and member of Lowell Song, has observed changes in attitudes around sexual assault in her interactions with other students. Tayag has noticed that male athletes treat her and her fellow female athletes with more care since the protests took place. These changes include maintaining physical boundaries and apologizing more often when those boundaries are crossed.

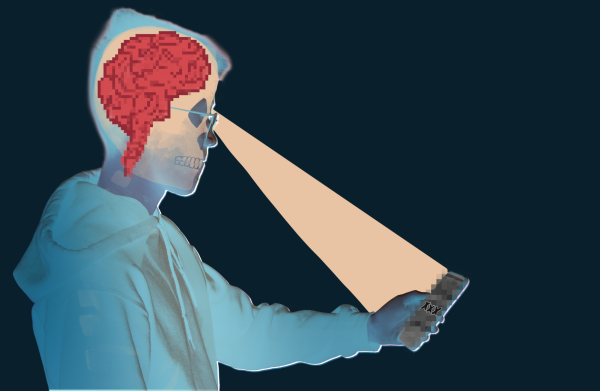

For survivors and advocates, this cultural change was a triumph that arose from widespread social media movements. However, some feel that there is significant room for things to spiral out of control when people are held accountable solely through a public trial by peers, whether it is through social media posts or word of mouth. According to Kang, when stories are shared online, the fallout can become dangerous. “I’ve seen people telling alleged abusers to kill themselves,” she said. “As well as other people condemning survivors for sharing their stories and saying they’re false.” Kang feels that students need adults to offer assistance throughout the reporting process. “When a child is sexually assaulted, teens can’t help alone,” she said. “It’s very dangerous to put someone’s case into social media and teens’ hands.” Nusrat believes that forms of public shaming of those who are accused is also not always a productive way of moving forward with a situation like sexual assault. “Shame doesn’t help people heal,” she said. “We want to keep [those who are accused] accountable but not shun them from society. This helps nobody.”

The level of intensity that the fall activism reached was successful in pushing attention towards the issue, but many organizers and supporters are struggling to maintain that level of advocacy. Sophomore Olive Girsang, an organizer of the Nov. 10 walkout, believes that the intensity of activism was necessary for drawing attention to the issue, but was also extremely draining for organizers to suddenly take on. “It was an attempt to create a safe space, which is exhausting because at the same time, you’re trying to take care of your own needs,” Gisang said. Other organizers of the Nov. 10 walkout, including Tayag and senior Aliyah Baruch, have also noticed that supporters who were less involved in the movement are having fewer and fewer conversations around the subject.

Though there have been shifts in perspective, survivors and activists feel that there have not been substantive changes in response to the protests. Baruch feels that very minimal action has occurred after the protests and countless conversations with administrators regarding organizers’ demands. Dominguez agrees that no actual written changes have been made following the protests. He feels that the administration has always handled sexual assault cases as best they could within the laws they are bound to. “We would’ve handled it in the same way [without the protests], where we would investigate appropriately and we would come to an outcome,” he said.

Though there have been shifts in perspective, survivors and activists feel that there have not been substantive changes in response to the protests. Baruch feels that very minimal action has occurred after the protests and countless conversations with administrators regarding organizers’ demands. Dominguez agrees that no actual written changes have been made following the protests. He feels that the administration has always handled sexual assault cases as best they could within the laws they are bound to. “We would’ve handled it in the same way [without the protests], where we would investigate appropriately and we would come to an outcome,” he said.

Instead of written policy changes, students and faculty of Lowell are beginning to emphasize the need for education around consent and the rights of students for sexual wellness. According to Dominguez, in response to student demands, the Wellness Center has sought more ways of implementing sexual assault and harrassment education into classrooms. Dominguez feels that the administration has emphasized the need for school-wide education on the details of reporting and handling cases of sexual assault. This manifested in a student rights and responsibilities handbook that is in the process of being made, and more posters about students’ rights under Title IX being put up. “Everyone needs to be educated better on what the process is and what is not considered Title IX,” Dominguez said. Baruch echoes the need for education on consent and legal rights and believes that the Title IX posters put up by the administration are a step in the right direction.

As Lowell continues through the process of addressing sexual violence in the community, many people are looking towards what comes next. Dominguez wants to minimize the divide between students and administration so that the community can unite to combat the issue. “I don’t want us to continue this idea that it’s students versus admin,” he said. “I promise we are all on the same side.” It has been a few months since the last widespread protest and fewer and fewer posters are being put up. While conversations around the handling of sexual assault at Lowell have lessened, many advocates are determined to make sure that people don’t turn their heads from the issue. “We’re not done,” Baruch said. “This time we expect more.”

Angela is a senior at Lowell who recently bought a membership at the Stonestown movie theater. In addition to watching movies, she loves to sing and is part of Lowell’s concert choir. Despite this and her 6 years of experience playing volleyball, her greatest skill is procrastinating.

You can usually find Dary blasting music in her airpods and speed walking around in outfits she spent too much time thinking about, or that embodies the Adam Sandler within her. She loves to chat, so feel free to say hi or ask for help!

Yeshi (yEEshi) is a senior at Lowell that loves the school breakfast bagels a little too much. After school hours, you can find her at the beach or in the park daydreaming about almost anything and everything.

Libby is a photographer and multimedia editor for the Lowell; taking on the world with a camera in one hand and a Peet's coffee cup in the other. She is a very contemplative soul, and you may often find her pondering large and abstract philosophical ideas (see staff profile photo). Libby also enjoys writing silly little staff profiles about herself instead of doing her English homework!!

Kelcie is a senior at Lowell who can be found in the journ room working, drinking coffee, and listening to music. Her older brother once mentioned that there are only three guarantees in life: death, taxes, and Kelcie not waking up to her alarms. She also happens to have a paradoxical relationship with chicken… go figure.