Korean beyond a trend

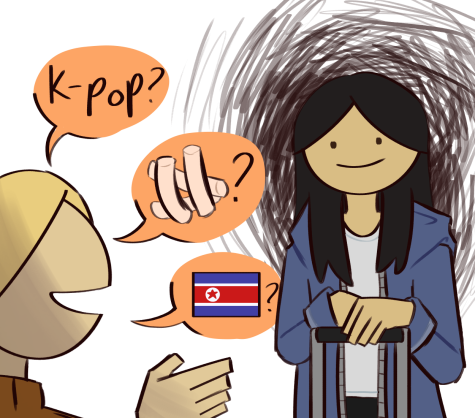

I stood in the long line that meandered through the airport corridor, scanning the menu. The white woman standing next to me, upon hearing that I was headed to South Korea, was still raving about K-pop singers and rice cakes, despite my increasingly obvious attempts to end the conversation. Almost as if on cue, she stopped, but my relief turned into dread when she asked her next question: “Have you ever visited North Korea?”

Over the past few years, East Asian representation in Western media and society has progressed from very little acknowledgement to more substantial inclusion. However, cultural acceptance and appreciation as a result of the recent uptick in popularity has begun morphing into fetishization and objectification, a shift I wasn’t even aware of until I reevaluated how the relationship between Korean culture and Western media influenced my own interactions with the world around me.

Growing up, my Korean identity was never something that I expected people to notice. Because East Asian representation in Western media was so limited — if featured, Asian characters were often limited to stereotypes or small supporting roles— I had to look to non-American media to see even a glimpse of Korean people featured at all. This lack of substantial representation gave me a sense of cultural inferiority.

In more recent years, it’s been refreshing to see more Korean representation in American pop culture. To many, PSY’s hit Gangnam Style was just a catchy song from an obscure Asian country, but to me, it was the first big moment of recognition for Korean music that began to unravel my lingering sense of obscurity.

Today, Korean pop culture is in high demand, and I’ve witnessed it get long overdue recognition. In 2021, Minari actress Yuh-Jung Youn was the first Korean to win an Academy Award, and BTS was the first Korean act nominated for a Grammy in its prestigious 63-year history. These breakthroughs would have never been imaginable a few years ago.

It’s strange to witness an aspect of your identity that has distinctly shaped you since birth suddenly explode in popularity. Hearing popular Korean songs on the radio, in the language I used to feel uncomfortable speaking in public, was a breath of fresh air, albeit a little surprising. Rather than being alienated from pop culture, my identity suddenly embodied it, and it seemed that Korean identities were finally being acknowledged and appreciated!

But there was something about this sudden shift that felt inauthentic. This was confirmed by the rapidly growing popularity of Korean culture coinciding with the spike in anti-Asian hate crimes. It felt like this newfound “acceptance” cherry picked the trendy parts of Korean culture and didn’t acknowledge it as a whole. During the lockdown period of the pandemic, going on social media meant scrolling past countless videos of Asians being harrassed, mocked, and degraded. Anti-Asian hate crimes in America rose by 76 percent in 2020, and that’s just the ones that were reported. Squid Game did become the first top-ranked Korean series on Netflix, but could it really be counted as a win if my parents were afraid to go outside and walk the streets during the wave of violence?

Even then, I didn’t realize why I felt unsettled by this sudden rise in popularity until I stumbled across an old Seinfeld skit where, after being called racist for saying he likes Chinese women, Jerry responds, “If I like their race, how can that be racist?” At first, I saw no fault in his argument. Racism was about hate, so if Jerry confessed his desire for a particular race, how could it be racist? I drew parallels to the current situation, where aspects of Korean culture were being popularized in the name of acceptance and inclusion.

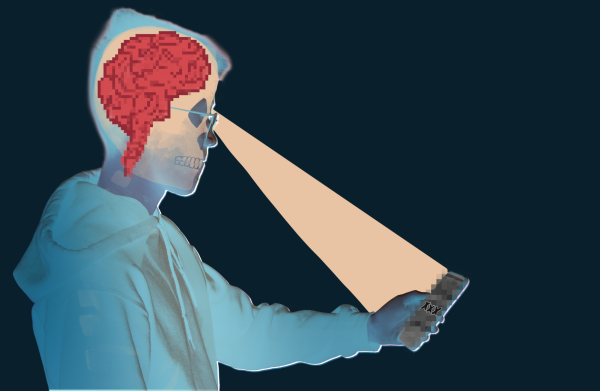

However, the more I likened the flaws in Jerry’s argument to events I had seen in real life and on social media, the more I began to question the motives of this newfound “acceptance”. At the root of some of my discomfort was the revelation that there was an extremely fine line between appreciation and fetishization, and it was being crossed often. I realized that seeing prevalent K-pop singer comparisons in any random Korean person’s social media comment section (“Wow, you look exactly like Jungkook!”) was just another, more insidious, form of racism. Comparisons like these pushed a diverse group of people into one category and forced preconceived ideas onto them, ultimately erasing their diverse identities and personalities.

Consequently, I began to pinpoint specific instances in my life, as well as many of my friends’ lives, that had crossed this line. When the woman at the airport saw me, she saw good food, catchy music, and fun TV shows, rather than a normal multifaceted individual. Although it appeared to be admiration on the surface level, I felt just as frustrated as I had when Korean representation was at miniscule levels. Once, while reading a news article about a man who longed to become Korean after consuming K-pop music, I grew uneasy. He wanted to embody Korean culture, despite being unaware of the rich history of struggle that has shaped South Korean society today and the issues that currently plague South Koreans, such as blatant colorism or gender inequality. When people cherry-picked elements they liked while glossing over these issues, it told me that their interest wasn’t in the actual culture, but what they wanted it to be, which further solidified my doubts about the authenticity of its current popularity.

There’s nothing wrong with enjoying and embracing other cultures. In fact, I think it should be encouraged. However, I now realize that Western media’s fixation on Korean culture can have harmful side effects, such as the creation of a superficial, romanticized version of it. It leaves me feeling just as uncomfortable as the lack of representation had, although the circumstances are admittedly different. Of course, I can’t do much to change the way my culture is picked apart and portrayed in more popular spaces, but I urge everyone who’s taken interest in the culture to acknowledge and embrace Korean identities beyond pop culture.

Chloe is a senior, but still doesn’t really feel like one. One thing she’s proud of are her spotify playlists, which include every genre imaginable (yes, even country). Outside of the journ room, she loves taking long drives, writing, and thrifting.

Yeshi (yEEshi) is a senior at Lowell that loves the school breakfast bagels a little too much. After school hours, you can find her at the beach or in the park daydreaming about almost anything and everything.

Charon is an illustrator in their senior year. They are non-binary and use they/them pronouns. Usually just a homebody with a love of the post-apocalypse and wild west genres. As well as an eye for collecting charms, pins, patches, and other knick-knacks. Currently hemiplegic and recovering from a stroke.