Failing to sleep

Senior Chris Tan walks into his seventh block pre-calculus class and slumps into his chair, exhausted from having gotten just one hour of sleep the night before. As his teacher approaches his row, passing out tests, Tan waits, eyelids heavy. Attempting to fight his exhaustion, he sits up and glances at the paper before him. As he searches for any recollection of the equations he studied the night before and earlier that day, his mind goes blank. Frustrated by the failure of his Trader Joe’s matcha shot to kick in properly, Tan sits in his chair, brain empty. Crippled by a lack of sleep, he is left staring at the piece of paper, feeling utterly helpless.

This is not an uncommon experience among Lowell students.

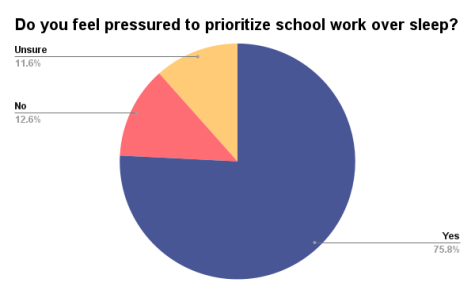

Sleep deprivation is an ongoing issue that affects many students at Lowell. Bleary-eyed students have noticed the ramifications on their mental health and academic performance, as a lack of sleep sometimes causes them to fall asleep in class or renders them unable to focus. However, this problem is not the result of singular actions by students; it is a cultural issue. Lowell’s academic environment causes students to prioritize success over sleep in some cases, perpetuating a culture of sleep deprivation.

A lack of sleep is a commonly faced issue among high school students across the United States. Sleep deprivation — the situation or condition of suffering from a lack of sleep — can result from a variety of influences: insomnia, excessive amounts of homework, stress, caffeine consumption, phone addiction, and procrastination. According to AP Psychology teacher Kristin Lubenow, who has a degree in psychology, the average high school student needs between eight and ten hours of sleep each night in order to be healthy. Lubenow stresses the importance of adolescents getting a sufficient amount of sleep. The ramifications can be serious, she warns, such as lower academic performance and decreased mental well-being. “You’re obviously not going to be able to think as quickly and not be able to problem-solve as quickly,” Lubenow said. “You’re not going to be as resourceful in terms of your coping mechanisms. So also, psychologically, you may be more irritable.”

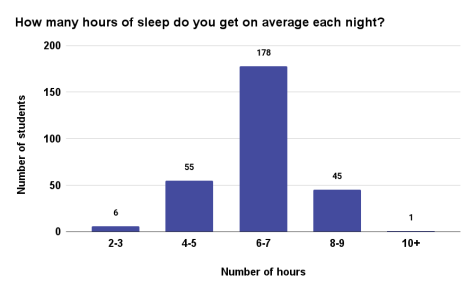

With Lowell’s heavy academic workload, getting a sufficient amount of sleep is almost impossible for a majority of students. According to a survey administered by The Lowell, 63 percent of students feel that they don’t get enough sleep, and 67 percent attributed this to a heavy workload from school. In senior Colin Cabreros’ case, he is often forced to stay up late in order to finish his homework. “I try to go to bed by 10 or at least, try to wrap everything up by 10,” Cabreros said. “But most of the time, I would go overtime with the work I have because I have more work than needed or than I should have, and it usually hits midnight.”

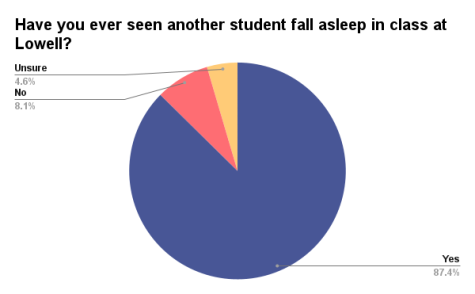

The effects of sleep deprivation are evident in many Lowell classrooms. According to a survey administered by The Lowell, 50 percent of students have fallen asleep in class and 87 percent have witnessed another classmate do so. For freshman Ella Finse, seeing students fall asleep in class is a common occurrence. “Everyday there are two or three people I can rely on that will fall asleep in class, and there’s one kid in my first period that cannot keep his eyes open,” Finse said. “I just feel so awful for them.” While Finse has yet to fall asleep in class, Tan, who sleeps one to three hours a night, falls asleep in class about once a week. “There are a lot of instances of me just dozing off during a lecture,” Tan said. “Just relying on caffeine eventually just doesn’t work.” Senior Kaydence Wu has noticed how not getting enough sleep has made it hard for her to focus and digest teachers’ lessons. “I’ve been burning out,” Wu said. “I can’t retain information from class lectures, which I think is a huge problem.”

In October of 2019, California Gov. Gavin Newsom passed legislation to combat student sleep deprivation. The bill, SB 328, prohibits most middle schools from starting the regular school day any earlier than 8 a.m. and most high schools from starting the school day any earlier than 8:30 a.m. The San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) opted to implement later start times by August 2021, despite the deadline for compliance not being until July 1, 2022. Lowell’s new bell schedule, in compliance with the district mandated later start time, begins at 8:40 a.m. and ends at 4 p.m.

Following the passage of the senate bill, the school day now officially starts later, but not every student benefits. Lowell retained its policy of offering seven classes, by offering a Block 0, in addition to the six instructional blocks and lunch. Each class period was also extended by five minutes. Students who opted to take a Block 0 class start school at 7:40 a.m. – an hour earlier than the start time mandated by SB 328. This technically does not violate the bill since participation is entirely optional. Cabreros thinks students who are attending a Block 0 class, and those who live far away from Lowell, are not benefiting from this schedule change as they still have an early start to their day, going against the original purpose of the bill to combat sleep deprivation. According to Cabreros, who is taking seven classes, the extreme workload, along with having to sit through many classes in a row, can be very tiring. Additionally, he often finds himself feeling drowsy during both his Block 0 and Block 7 classes. “Having to sit through that many classes without doing much is definitely mentally draining,” Cabreros said.

With the issue of sleep deprivation becoming increasingly apparent at Lowell, some students have noticed a distinct culture surrounding it. Finse, despite only being at Lowell for four months, has already noticed this culture. She believes that students view sleep deprivation as a sign of academic success. “I think that that’s really damaging because it makes the idea that in order to be smart and in order to be the ideal student, you can’t get enough sleep, and that’s just really not healthy,” Finse said. This culture at Lowell has started to infect Finse’s own thoughts. She believes that if she participated in more extracurriculars, she would be getting less sleep and that a smaller amount of sleep is more desirable because it reflects your success. “I should be getting that much sleep, and it had this pressure on me that I’m not doing enough,” Finse said.

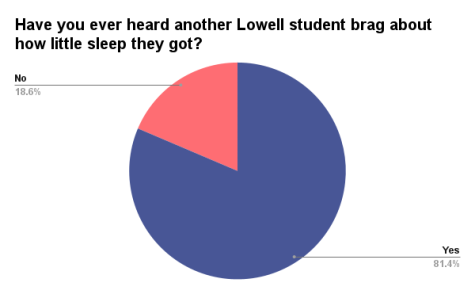

One of the problems preventing change on this front is that Lowell students may be resistant to shifting their sleep schedule. According to the same survey administered to Lowell students, 81 percent of Lowell students have witnessed another student bragging about how little sleep they got. According to Wu, students see sleep deprivation as a way of proving their commitment to their schoolwork and other obligations. Wu, who sleeps an average of five hours each night, has noticed students competing and bragging about their lack of sleep on several occasions. “I feel like it’s to the point where I try not to say anything because I feel like it’s a contest. There’s always somebody trying to one up you,” Wu said.

For students who do maintain a healthy sleep schedule, homework levels can become near impossible to manage. Sophomore Omar Hidrogo’s parents moderate his sleep schedule by ensuring that he goes to sleep by 10 p.m. Parental oversight, along with a long commute to school and distractions at home, leaves him with little time to do homework. As a result, Hidrogo uses every moment of downtime to do schoolwork. “It’s very stressful,” he said. “I cram every single minute I get to do homework. Whether that be every lunch block, on the MUNI, or during class.” Hidrogo believes that the expectation to complete all of his assignments and sleep the recommended eight to ten hours per night is an impossible task; his sleep schedule often results in unfinished assignments. “It enrages me because it’s really a big double standard,” Hidrogo said. “It’s not reasonable or attainable.”

Another factor that contributes to sleep loss is procrastination. Cabreros believes that while it is important that students prioritize sleep over academic success, poor time-management skills are partially to blame for excessive sleep loss among students. “[Students] still have late-night study sessions or procrastinate to the last minute for assignments,” Cabreros said. Wu has also fallen victim to procrastination and distractions, which she attempts to combat using different methods, including putting her phone on do not disturb, preventing notifications from alerting her while she is doing work. “I’ve found that I’ve been picking up my phone less frequently,” Wu said. “I try to get in the zone to just be productive and get my work done.”

Students and teachers feel that one possible solution to the issue of sleep deprivation at Lowell includes revisiting and changing the bell schedule. Cabreros believes that shortening the school day is necessary and that the extended time for each class was a mistake. “That’s five extra minutes, and sometimes, the teachers don’t even use those five extra minutes, and they just account those for passing periods,” Cabreros said. “I think just cutting that amount of time off would be pretty substantial.”

Lubenow believes the number of classes that students choose to take perpetuates sleep deprivation as well. Because of this, she feels that rethinking Lowell’s bell schedule may be necessary but that would only be part of the solution. “Clearly [the bell schedule] is a little problematic, but that also means potentially changing the culture of Lowell, and no longer allowing students to actually take seven classes,” Lubenow said. “So there’s a lot of working parts there that make it very complicated and challenging.”

Another possible way to increase the amount of sleep that Lowellites get is to decrease students’ homework. Cabreros believes that with current workloads, students cannot get enough sleep. “I think teachers could try to sympathize more with students, really, and just, I think, be wary of the amount of work they put out onto the students,” Cabreros said. “It would be more beneficial for teachers to spread out, and lessen the amount of homework they give.” Lubenow supports this sentiment as she believes that reinforcing material taught in class may only require a few questions rather than many. She believes that teachers should reevaluate the workload they are assigning. Finse feels that it’s important for teachers to try to assign workloads that are more manageable for students and acknowledge students’ lack of sleep and their erratic sleep schedules. Finse has noticed her teachers’ consistent advocacy for getting enough sleep, but the constant assignments that pile up beg to differ. “With some other teachers it feels a little ironic and hypocritical for them to be saying, ‘Make sure you’re getting a ton of sleep,’ but then to assign a lot of homework,” Finse said.

Tan believes that the culture of sleep deprivation at Lowell goes beyond competition. In his experience, it often stems from a desire for students to prove that they can handle the workload at Lowell. Still, he also feels that this culture of sleep deprivation will always be deeply rooted in the school. “I feel like even if we didn’t make it a competition, it would still occur,” Tan said. “Because, at Lowell, it’s still difficult to get high amounts of sleep.”

Kelcie is a senior at Lowell who can be found in the journ room working, drinking coffee, and listening to music. Her older brother once mentioned that there are only three guarantees in life: death, taxes, and Kelcie not waking up to her alarms. She also happens to have a paradoxical relationship with chicken… go figure.