Breaking the shame of broken English

“Wait!” A car door slammed as I turned my head, the sound echoing in my ears. I watched my father step to the sidewalk and run toward me, gripping my lunch box in his outstretched hand. Cold sweat swept across my skin as I stepped aside to allow the steady flow of students to pass. “You forgot lunch,” my father said as he reached me, pressing the thermos of fried rice into my hands.

Hearing his strong Chinese accent — the unnatural flaws in his speech and how the English words stumbled awkwardly from his tongue — sent heat prickling across my face before my whole body went numb. It was the first day of my junior year, and being more aware of my image than normal, I felt the burning stares of a hundred students even though there were only a dozen nearby. Accepting the lunch with shaking hands, I stuffed it into my backpack and quickly turned away. To link myself with him would be to associate myself with a family that doesn’t fit into American society, I thought. All my life I had seen too many people’s faces contort in confusion, their lips twisting into condescending smiles, as they tried to understand what my parents were saying.

That night, I told my parents to either speak Chinese in public or to not speak at all.

Although it’s difficult to comprehend now, I know I didn’t always feel this way. In elementary school, a place where childlike ignorance melted away any concerns about how others perceived me and my family, accents were invisible. I thought my parents sounded like I did: articulate, eloquent, and American — normal. Deaf to what made my parents different, I didn’t have to worry about what other people thought of them and what they’d see when they turned their attention to me.

Throughout my childhood, I was endlessly proud of what my parents had accomplished. My father always used to tell me that he graduated from the best school in China, Tsinghua University. My mother, refusing to pale in comparison, boasted about her admittance to a top college for athletics. As a result, my younger self placed them atop lofty pedestals. I bragged about their successes to all of my classmates and even brought their pictures in for show-and-tell.

In 5th grade, my mother delivered a speech in front of my entire elementary school. Hearing her ringing voice reverberate throughout the auditorium, I realized for the first time that her accent wasn’t normal. I jerked in surprise when I heard it: a thick Chinese accent amplified by the microphone, which was set too close to her lips. She stressed the wrong syllables, voiced the English words in unnatural, jagged tones, and my eyes were opened to the gaping difference between her and everyone else. My parents had fallen from their pedestals of academic prestige.

The spotlight was on my mother, but I felt the eyes weigh on myself, suffocating me. When she stuttered and pronounced a word incorrectly, it seemed as though the entire audience simultaneously nudged each other. By the time she stepped off the stage, I couldn’t even look at her because the whispers of scrutiny were alI I could hear. Ignorant of her jubilant grin and inflated ego, I stopped her from mingling about after the event and dragged her away.

When I became aware of the graceless way my parents spoke, everything changed. Their accents and their worth became intrinsically

intertwined, and suddenly their accomplishments didn’t seem as impressive.

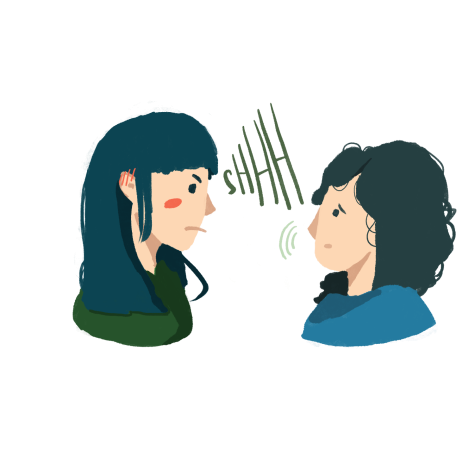

From then on, I took it upon myself to save my mother and father from what I perceived was humiliation. I shushed them every time they spoke too loudly in public. I intervened when they struggled to clearly communicate their ideas, cutting off their words and speaking for them in what I believed to be a more respectable manner. I ordered for them at restaurants and tried to ignore their crestfallen expressions as their sense of individuality was destroyed. At home, I condescendingly corrected them, and grew frustrated when I couldn’t mend the cracks in their broken English. “Maybe you should get an English tutor,” I once told them.

At the same time, however, I felt guilty about silencing my parents. Nagging thoughts constantly lurked in the back of my mind, accusing me of cruelly dismissing the rich history laced within my parents’ voices. They had immigrated from China with nothing, and learned English on their own by spending eight hours every day in the library for a year. Wasn’t that something to be proud of? Even if they didn’t speak with accents reflective of conventional, Western speech patterns, did that mean they were less intelligent? What gave me the right to dictate what they could and couldn’t say? Guilt pushed these questions to the forefront of my consciousness.

To alleviate the heavy shame that hung like a weight in my chest, I began to loosen my grip on my parents’ speech as middle school flew by. When they cautiously began to speak more freely in front of me, I found that my instinct to interfere had become almost dormant. But still, every so often when my mother butchers the pronunciation of a word or my father shouts goodbye too loudly in the school parking lot, that urge reawakens briefly as a sharp ache grating against my chest. However, as evidence of their perseverance in a completely new environment, their unconventional English is actually something to be proud of.

I am trying to accept that there is no reason to be embarrassed or ashamed of my parents’ accents. The way they speak reflects their own triumphant histories. I now rejoice in my realization that my parents are people to be proud of, regardless of the way they pronounce their words. If I ever begin wishing for them to stop talking or catch myself trying to speak for them, I will remember that my mom went to a fantastic school for sports. My dad went to the top school in China. My parents successfully immigrated to America and overcame the odds stacked against them.

I am proud of my parents, their rich histories, and their steady dedication through hardship. Their accents are symbols of their strength, a complex tapestry illustrating a journey to be treasured. I know that now.

Angela is a senior at Lowell who recently bought a membership at the Stonestown movie theater. In addition to watching movies, she loves to sing and is part of Lowell’s concert choir. Despite this and her 6 years of experience playing volleyball, her greatest skill is procrastinating.

Libby is a photographer and multimedia editor for the Lowell; taking on the world with a camera in one hand and a Peet's coffee cup in the other. She is a very contemplative soul, and you may often find her pondering large and abstract philosophical ideas (see staff profile photo). Libby also enjoys writing silly little staff profiles about herself instead of doing her English homework!!