A closer look at Lowell’s Special Education program

By Katherine Nguyen

Junior Gerard Tavares has been on Lowell’s swim team since his freshman year.

He competes in individual medleys, freestyle, free relay and backstroke races. He placed fifth in the JV boys’ 50-yard backstroke event at All-City finals last season. Even outside of Lowell’s swimming season, Tavares doesn’t stop swimming. He practices everyday, and at least once a month he enters the USA Pacific Swimming competition.

But unlike other swimmers on the team, Tavares has autism — a developmental disability that includes a wide variety of symptoms — such as repetitive behaviours, language disability, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines and unusual responses to sensory experiences.

Tavares is also the first student with autism at Lowell to qualify for the swim team without any accommodations. Outside of school, he also swims for the Special Olympics of Northern California and is a novice with the USA Paralympics, teams for mentally and physically handicapped athletes.

Tavares was diagnosed with autism at three and a half years old, and he is eligible for Special Education, a school service that assists students with special needs and disabilities at no cost to the student and their family.

Special Education is an umbrella term — there is no set of symptoms that defines every Special Education student. It serves students with a large range of disabilities due to developmental delays and difficulties, such as autism, sensory issues, speech/language impairments and emotional disturbance. Every Special Education student has his or her own needs.

Thirteen percent of public school students in the US ages 3–21 received special education services in 2013–14, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Of these 6.5 million registered students, about eight percent have autism.

Lowell offers several Special Education programs separated by the severity of the student’s symptoms. Some programs support students placed in general education classes, the regular classes that most of Lowell’s students take. Others programs are Special Day Classes, Mild/Moderate and Moderate/Severe, that support students whose needs cannot be met by the general education classes. During the 2014–15 school year, a little more than 100 students were enrolled in Special Education at Lowell.

What is inclusion?

One of the goals of Special Education is to offer students the right amount of support — not too much, and not too little. This is a federal requirement known as the Least Restrictive Environment. Under LRE, Special Education students can’t be removed from regular classes unless the benefits of being in those classes are unsatisfactory.

LRE is part of the idea of inclusion — the goal for students who demonstrate a particular level of learning ability to participate in general education classes and learn from their peers who don’t have disabilities.

To address their specific needs, each student that enters Special Education is required to have an Individualized Education Plan that lists the necessary accommodations specific to the student. These accommodations are determined by a team of the school staff and the child’s parents. Depending on the student’s needs, teachers may tailor material and assignments to better fit the student’s level of learning.

Stephen Torres-Esquer, who teaches Special Day Classes at Lowell, emphasizes that the importance of inclusion is not always on the student simply keeping up with the work and curriculum. Instead, he wants to ensure that his students are exposed to other children their age. The daily inclusion with peers can lead to social and emotional development of students with autism as they see how their peers in general education interact and behave socially.

Thirteen percent of public school students in the US ages 3–21 received special education services in 2013–14.

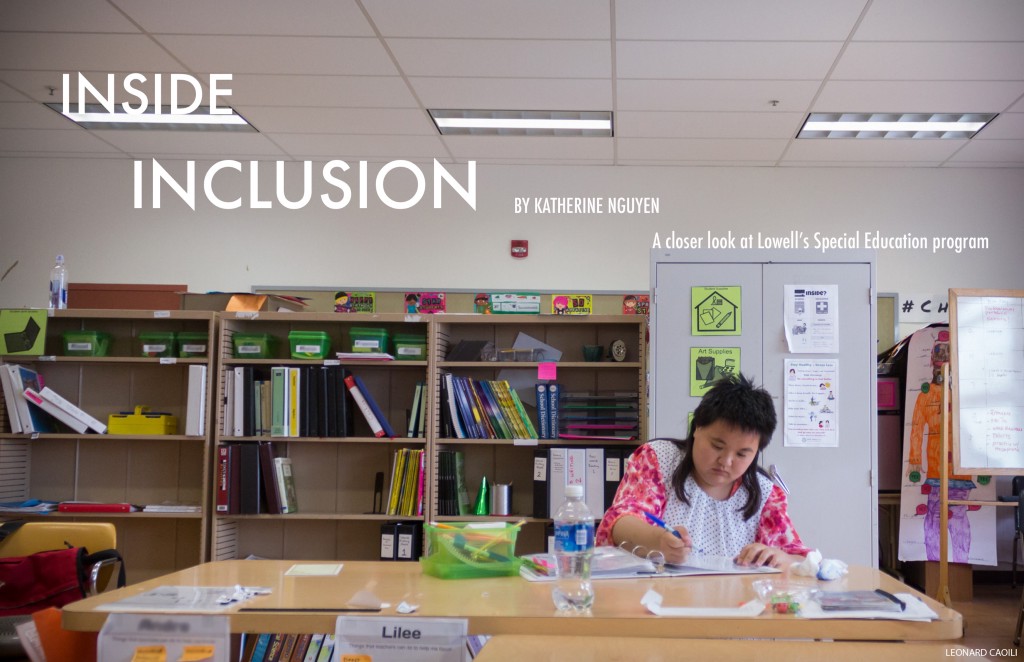

In Torres-Esquer’s Special Day classroom, students have desks with nametags with Post-It notes saying “Things teachers can do to help me focus.” Their personal aids are seated beside them, ready to provide whatever aid necessary, whether it is helping the student to process instructions or helping them with the actual material. With 10 students in his Block 8 class, Torres-Esquer can work on an individual basis with each one.

Student and Parent Perspectives

Junior Lilee Consoer, who has moderate symptoms of autism, spends most of her time in Torres-Esquer’s Special Day Class and the rest of her day in general education classes. Last spring, she was in Physical Education and choir.

How Consoer learned to act and participate in the choir classroom from observing her peers is an example of the challenges and benefits of inclusion.

As a freshman in her choir class, Consoer sang loudly and enthusiastically, but often shouted out the song, which drew attention to her. By junior year though, she learned from listening to the students around her to pay more attention to the pitch, choir teacher Jason Chan said. She doesn’t draw as much attention to herself anymore.

Consoer said that she likes singing in her choir class, even though she doesn’t really like hanging out and talking to the other students a lot.

Torres-Esquer said that by creating a positive, accepting atmosphere, general education students can help Special Education students feel less discomfort at initiating conversation or interaction with their classmates.

The Lowell interviewed Consoer in her Special Day Class about general education classes as she was working on an assigned art project, cutting Dorito chip bags into pieces to make stained glass art. Torres-Esquer said that Consoer would need more prompting than a general education student to keep up a conversation.

“Do you like hanging out with the kids in those classes?”

“Not really, no,” Consoer said, focusing on cutting out her Dorito bag. “Sometimes.”

“Is there a reason that you don’t like to, or do you just not feel like it?”

“Just not,” Consoer answered. Her artwork was starting to come together, and she remained focused on putting pieces together as we talked.

“Is it because you feel uncomfortable, Miss Lilee?” Torres-Esquer asked.

“Yeah,” Consoer said, snipping out another piece of a bag for her stained glass.

Consoer expressed more excitement when we spoke about what her favorite class was. “Art!” she said without skipping a beat. She works on her art projects in the Special Day Classes she has with Torres-Esquer, who showed a brightly painted stick with polka-dots and a spray-painted mask which Consoer had made in a previous class.

Tavares, in addition to being on the swim team, is another of the 10 students in Torres-Esquer’s class.

Tavares’s symptoms are less severe than Consoer’s. His language, like Consoer’s, is simpler than the average teenager’s. But he enjoys initiating conversation and was quick to introduce newcomers to his experiences in Special Day Class.

Cheerful and engaging, he was eager to show visitors around the classroom. He took out his portfolio, spreading pages of his classwork on the table and said with enthusiasm: “We’re doing money math.” He explained the class’s trips to Ross and other stores at Lakeshore plaza, where students have lunch, navigate through the shops and learn to interact with staff. Tavares said his money math comes in handy there, when he has to remember to round up when paying for an item so that the cashier can give him the proper change.

Tavares and Consoer both also work at Petco, where they handle products and stock shelves.“I like working there a lot,” Tavares said. “It’s fun. I organize the shelves and items, and I can also look at the animals.”

Providing opportunities and support for students with disabilities can be demanding on parents. For Tavares’s mother Luisa, her son is the focus of her life. She was paying out of pocket for day-care and therapy, and working brought in money that she put towards helping her son. But she realized that she could do more if she had the time to focus solely on her child, so she gave up her job. “It was hard for me to stop working,” she said. “But maybe, I said to myself, I would be able to focus on my son. It’s a sacrifice.”

Quitting work gave Luisa Tavares the time she needed to bring her child to therapy and programs. He had all the symptoms of autism when he was first diagnosed — he couldn’t have conversations at all, instead only repeating what others said to him. But now the programs she had invested her time in after quitting work have improved her son’s life greatly. “Right now, he does conversations,” she said proudly. “Not as good as a regular teenager. He does it like a nine year old, but at least it has improved a lot.”

Stereotypes about Special Education

Since the passage of IDEA, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, in 1975 and other recent laws that have provided aid to students with disabilities, it has become easier to find acceptance in school communities. But even with the growing efforts to include students with disabilities in general education, many students still face the struggle of overcoming the negative stereotypes placed on them.

One Special Education junior with high-functioning autism, a less severe form of autism that allows him to perform at the level of his general education peers, has had experience with inclusion in general education classes throughout his years at Lowell High School. This junior requested not to have his name published. His symptoms are mild — he has some sensory issues that cause him to have a hard time with noise. Most of his problems, however, exhibit themselves in the form of stress. Over the years, he has worked with these problems and learned, with hard work, to handle them well and to overcome them.

“It’s important to these kids that they are not invisible in the school.”

For this junior, inclusion worked because he’s at the academic level where he can take general education classes. “I don’t have a hard time at all fitting in with typical students, but for a lot of students it either doesn’t work or it’s very limited,” he said.

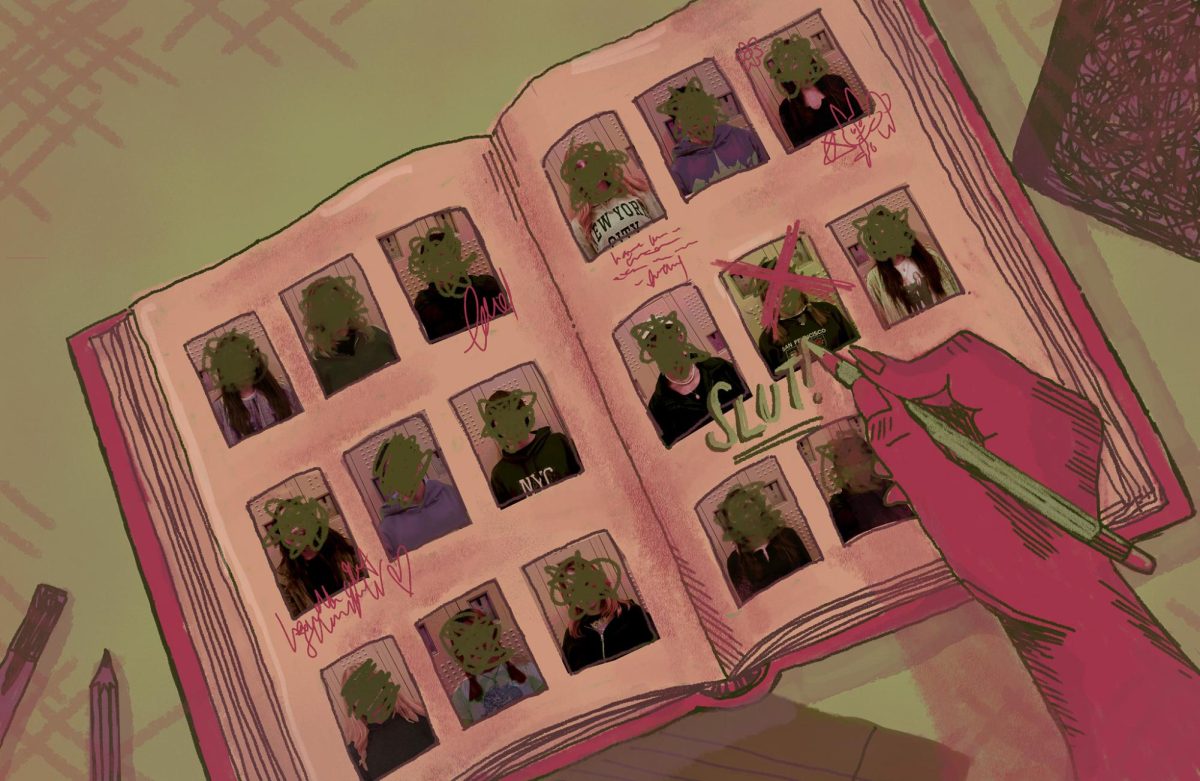

He has not often been directly affected by stereotypes in his time at Lowell, but he recalls a time in his general education math class when his classmates had been talking about and teasing another Special Education student who had a hard time recognizing what was socially acceptable.

He wasn’t aware of the situation until his teacher approached him and asked if he could lead a classroom discussion about learning disabilities and autism. He gave the class basic information on learning disabilities and autism.

During the discussion, he found that most of the students in the class were related to someone with learning disabilities. “Most people don’t realize how common learning disabilities are,” he said.

His teacher’s actions brought attention to the seriousness of these negative stereotypes.“People tend to infer that Special Ed kids are stupid or mentally ill,” he said. “These are stereotypes that are floating around out there, and these assumptions are not true. Conversations like these are important to have so that we can spread awareness.”

This student has been assigned to all general education classes as of this semester and is currently on track to get into college.

Stereotypes affect not only the students in Special Education, but their parents as well.

Luisa Tavares has experienced problems in the past with school staff, student community and stereotypes that people sometimes associate with her son. While most of these obstacles existed only in the middle school her son attended, she thinks Lowell could still work to find ways to undermine the assumptions other students often make about Special Education students. “When they see people acting different, they don’t treat them fairly, and they segregate them,” she said. These stereotypes often stem from a lack of knowledge on the part of general education students.

But while most of their peers’ assumptions are passive and quickly forgotten, some may lead to actions that directly hurt Special Education students. “There was a boy who bullied my son in junior high,” Luisa Tavares recalls. “He made my son get lunch for him. He thought he could pick on my son because of Gerard’s disability, and that Gerard wouldn’t fight back. My son was the one who ended up not being able to eat lunch.”

However, most of the student community can’t be faulted for not being taught about Special Education, despite its growing role in schools, she said. Tavares thinks it would be beneficial for the district to take the initiative to inform other students about Special Education and disabilities.

“Different is beautiful.”

“All the other Lowell students should be educated,” she said. “When they see these Special Ed kids, they look at them differently. Some people laugh and make fun of these kids. They shouldn’t be doing that.”

Lilee Consoer’s father, Keith, values inclusion as a remedy for these problems. “It’s important to these kids that they are not invisible in the school,” he said. “The more visibility they get, the less likely they’ll get bullied. It will make them feel more comfortable in being included in other classes.”

The Direction

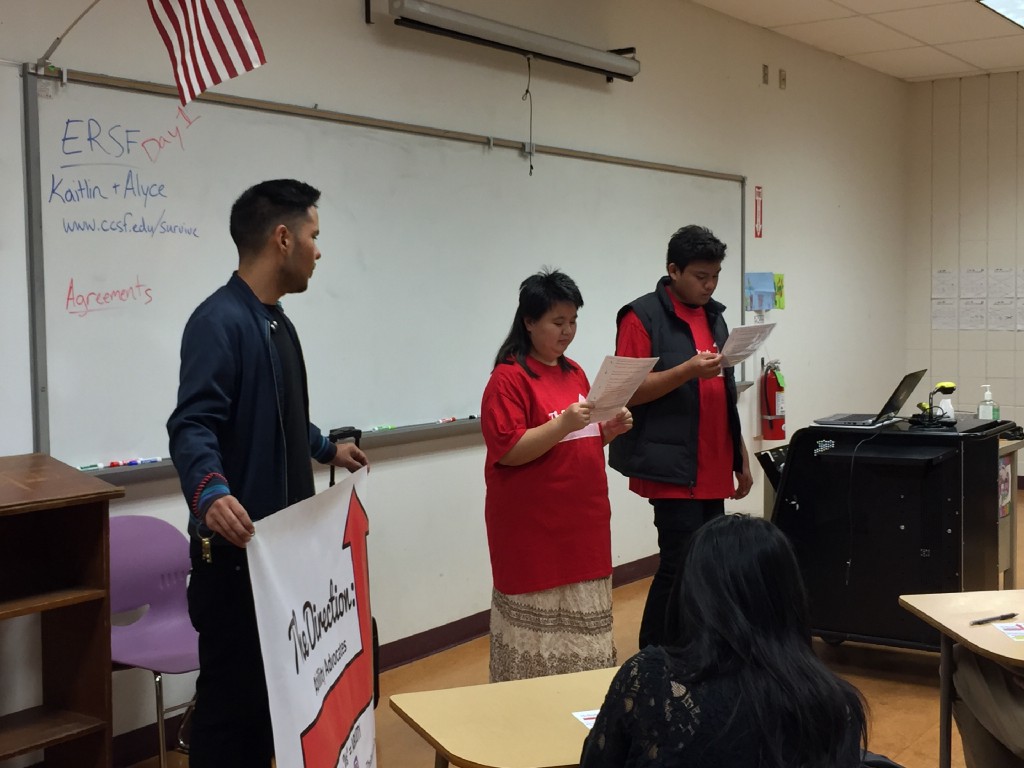

Lilee Consoer and Gerard Tavares have been advocating for the acceptance and inclusion of Special Education students in a group that Torres-Esquer started last year called The Direction: Ability Advocates. “Taking the ‘dis’ out of disability” is its slogan.

Torres-Esquer started the organization to provide opportunities for San Francisco youth with disabilities. His class was studying major rights movements — the first movement they studied was the civil rights movement, and they ended with the disability rights movement, which they spent the most time on. As a fun project for their curriculum, Torres-Esquer decided to start The Direction. From there, it expanded.

The organization, open to people with disabilities 12 and older and their families, has been presenting on and off campus for over a year, taking presentations to major festivals, such as the Cinco de Mayo festival and the Carnaval festival. Torres-Esquer has been collaborating with larger organizations, such as Habitat for Humanity and the YMCA, to help his students take its message beyond Lowell High School. With adult support, students like Consoer and Tavares can take part in community service activities that are usually off-limits to them.

Torres-Esquer and his students have presented to over 1,000 students at Lowell. On Sept. 15, they took their presentation to Norman Nager’s health classes. Consoer, Tavares, and other students brought with them a message promoting inclusion, respect and acceptance.

With help from Torres-Esquer, the students had decided what sort of people and “disabilities” they wanted to talk about in the presentation.“The people we see on TV, in magazines, and on the internet are beautiful. But that is not the only kind of beauty. Gay is beautiful… blind is beautiful… disability is beautiful…” Consoer read from her script. “Different is beautiful.”

“If we stand together to advocate, we can help bring attention to these problems and even stop some of them,” Tavares said in the presentation. “We have joined the fight against bullying, and we are going to win.”

The presentations and volunteer experience promote the idea that people with special needs don’t just need help, but that they can give it as well, Torres-Esquer said.

For now, only a select group of teachers in different schools around San Francisco are involved. They collaborate mostly when it comes to the community service opportunities, and Torres-Esquer continues to work to spread the organization’s message to other schools. Despite the challenges of bringing awareness to a school as academically oriented as Lowell, The Direction has accomplished a lot, said Torres-Esquer. He said that he’s begun to see a shift in the way teachers are seeing and treating his students and students in other Special Education classes. “That’s beautiful, because a lot of times we take kids into general education classrooms, and we call that inclusion,” he said. “But there’s a difference between being present and being included.”

Special Education department head Margaret Michels said that some teachers have worked with their individual students to do ability awareness presentations for their reg’s or other general education classes, but no teacher at Lowell has taken on this cause with quite the same size or scope as Torres-Esquer has.

Michels emphasized that people with disabilities are part of a population that has been marginalized in society. “For individuals with disabilities, the starting assumption is typically about what they can’t do,” Michels said. “The Direction is working to fundamentally change that perception.”