By Sofia Woo

Junior Takumi Mitchell is half Japanese and half white. He grew up in Lake County, which is 80 percent white and 0.2 percent Asian, three hours north of San Francisco.

He attended Clear Lake High School, where less than one percent of the students identify as Asian, and most of the students are white or Latino.

Being one of the only Asians, Mitchell dealt with some microaggressions. Students would always ask him questions like, “What kind of Asian are you?” In 2015, Mitchell’s sister participated in the county’s pageant and was crowned Miss Lake County. However, all the other kids at her school called her “Miss Hiroshima.”

This year, Mitchell transferred from Clear Lake High School, where he was in the minority, to Lowell, where over 50 percent of the students are Asian. He said being in Lowell’s environment challenged his identity because at his previous school he was known as being the only Asian student, which was an aspect that made him unique. “At first it was kind of shocking…when you come from a town of all white people and [then at Lowell] there’s a bunch of Asians around you,” Mitchell said.

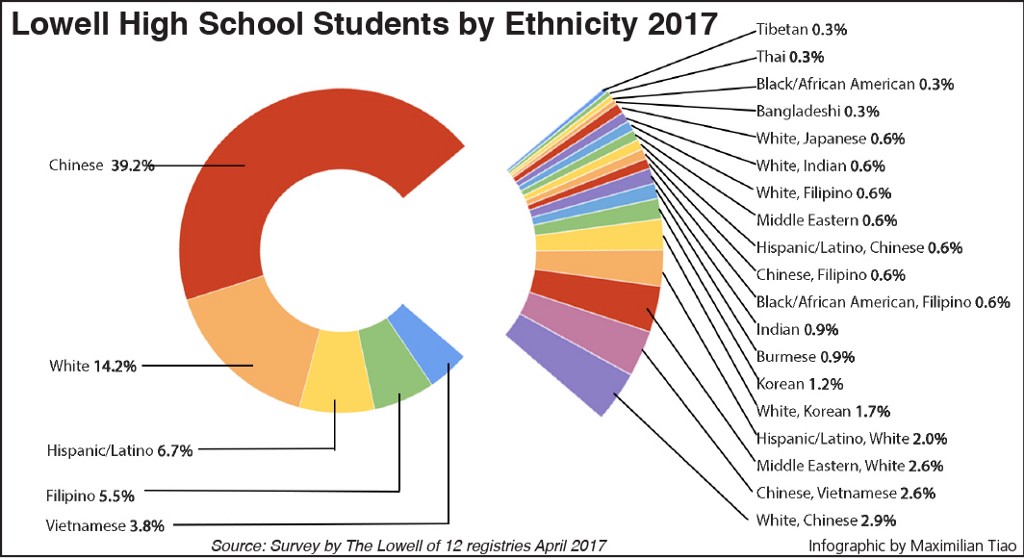

Lowell is 56.7 percent Asian. Other high schools in the San Francisco Unified School District also have high percentages of Asian students. Lincoln High School’s student population is 56.2 percent Asian, Galileo High School’s is 62.9 percent, and Washington High School’s is 62.3 percent.

School districts across America have fewer Asian students than SFUSD. Thirty-five percent of students enrolled in SFUSD are Asian, the largest demographic in the district. Oakland Unified, on the other hand, is 13.9 percent Asian. In New York City, Asian students are 11 percent of the student population, in Chicago, 3.9 percent, and in Atlanta, 0.8 percent.

Although Lowell has a significantly larger population of Asian students than other areas of the United States, Asian students still face stereotypes and other problems such as academic pressure and mental health issues.

What is the model minority myth?

Asian-Americans are the highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group in the United States, according to a 2012 survey by the Pew Research Center.

“Model minority” is a term for a minority group that has obtained higher education and socioeconomic status, through hard-work and self-reliance, than other minority groups. Today in the United States, Asians are considered a model minority.

The idea of a model minority is also often considered a myth, because it overgeneralizes about Asian-Americans. It can lead people to overlook the diversity of the Asian-American communities and the various struggles they face.

A majority-minority school

The Lowell conducted a survey in April to better understand the various ethnicities, family backgrounds, and issues faced by Asian-American students at Lowell.

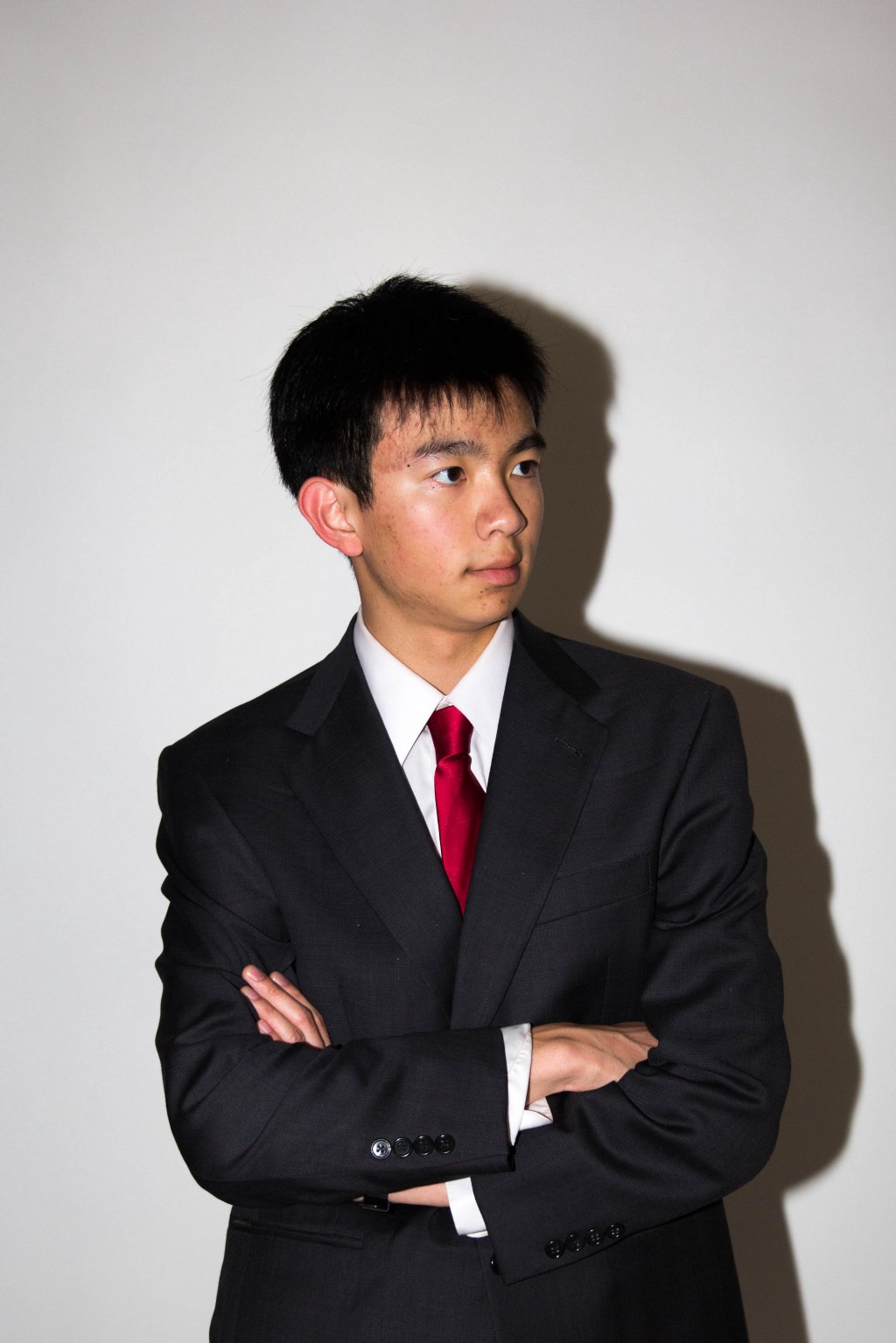

Senior Andy Huang is what many would consider to be, in terms of family background, a typical student at Lowell.

Like 39 percent of Lowell students, Huang identifies as Chinese.

Like 56 percent of Chinese-American students, he has parents who both immigrated to the United States. Huang’s parents immigrated from Guangdong.

Like 49 percent of Lowell’s Chinese-American students, he lives in a home where English is not the primary language.

Like 49 percent of Lowell’s Chinese students, he qualifies for the federal free and reduced lunch program.

And like 65 percent of Lowell’s Chinese students, Huang says his parents pressure him to do well in school.

Although he is a typical Lowell student demographically, Huang feels indifferent to this fact. Growing up, he said, he was always the common Asian kid as he wore glasses, played video games, and succeeded academically. Over the years, Huang had gotten used to the fact that he was the typical Chinese kid and it began to not matter too much to him.

“I just learned over time that it’s what you do and what you stand for that differentiates you, rather than some statistical factor,” Huang said. “Though I may be generic in name or appearance, it is my interests, passions, and other traits that set me apart.”

Challenges of immigration

Over 40 percent of Lowell students have parents who immigrated here to the United States, including 56 percent of Chinese-American students. This reflects a long history Asian immigration to San Francisco.

Since Asians began arriving to America in large numbers around the 1800s, they and other minority groups have faced numerous immigration policies that aimed to limit them from entering the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a major immigration policy that directly banned people from China from immigrating to the United States. With the Immigration Act of 1917 and National Origins Act of 1924, instead of just Chinese, other people from Asia were also banned. Only when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed, the number of immigrants from Asia in the United States started to rise significantly.

In 1907, the United States and Japan negotiated the “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” an informal agreement limiting the immigration of Asians particularly Japanese. At this time, SFUSD segregated Asian students into “Oriental Schools.”

Even though Asian immigrants have the highest rate of becoming college-educated, they and their families still face discrimination throughout all levels of schooling.

For example, students of a certain race may only associate with students of the same race, according to Russell Jeung, a Lowell alum and professor of Asian-American Studies at San Francisco State University.

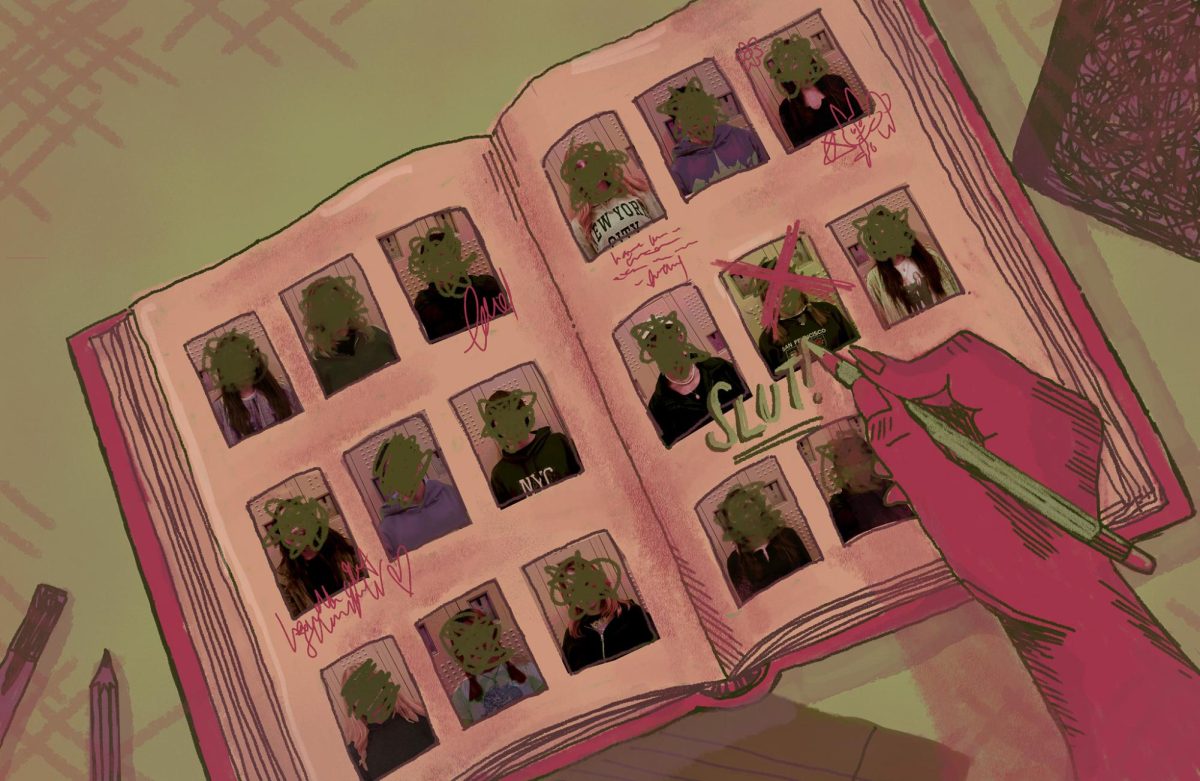

Some students segregate themselves because of bullying.

“Alex,” who requested not to use his real name for privacy reasons, is a senior at Lowell. He is half Chinese and half Vietnamese and has parents who immigrated to America when they were in their twenties.

Alex was bullied while attending E.R. Taylor Elementary School because of his race and accent. He also had very few friends, who were mostly Asians, so he was an easy target for bullying. Students would say to him, “Oh, you’re such a chink. You’re a FOB,” referring to the offensive phrase “fresh off the boat.”

Students would always ask him questions like, “What kind of Asian are you?”

He often found himself eating lunch alone. “All these kids have Lunchables and sandwiches, and I bust out a whole container of beef and broccoli with sweet and sour pork,” Alex said. “People would look at me and say, ‘Oh that’s weird. Why are you eating that stuff?’”

As he got to Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, Alex began to expand his group of friends to include all different ethnicities rather than only being around other Asians so he was bullied less.

Besides facing discrimination, immigrants, especially refugees and their families, have other challenges they must overcome in order to succeed.

Certain groups are allowed to enter the United States because they are professionals, such as engineers or doctors, or come from a higher socioeconomic class, while others are refugees who may not have been given the opportunity to achieve higher education, according to Jeung.

Senior Quang Truong’s parents left Vietnam in 1979. They became part of the “Vietnamese boat people” who fled from the Communist government after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Truong’s parents stayed in a refugee camp in Malaysia for two years and then immigrated to the United States. His family members moved from Albuquerque, New Mexico and Seattle, Washington to San Francisco and lived in the Tenderloin, a neighborhood known for its high crime rate, in the late eighties and nineties.

Despite having a disadvantaged background with almost no money and a poor understanding of English, his family managed to settle into a more financially stable status. His mother, for example, picked up trash and got a job on the side to support her family while maintaining straight As at Galileo High School. She was able to get a job as an accountant. One of his uncles earned a scholarship to attend a private boarding school in the east coast in sixth grade, and had the opportunity to do more with his life and escape the cycle of poverty to an extent, Truong said. His uncle eventually ended up becoming a researcher for AIDs and cancer medication in San Diego. “I feel a bit inferior by comparison,” Truong said. “I started out with all these advantages.”

Language barriers

Language barriers affect many Asian-Americans. According to the The Lowell’s survey, 49 percent of Chinese students do not speak English as primary language at home. The survey also found that 56 percent of students of mixed Vietnamese-Chinese background don’t speak English as the primary language at home.

According to the survey, 13 percent of all students and 20 percent of Chinese students are immigrants themselves.

Many immigrants need ELL (English Language Learner) or ESL (English Second Language) courses or teaching that acknowledges and is sensitive to language obstacles.

ELL programs have at least 30 minutes of specialized English instruction per day in the student’s primary language and/or English, with teachers who have certifications in teaching English Learners.

ELL courses are typically separated from general education classes. Lowell does not have separate ELL classes because only 1.8 percent of students are classified as ELL. Lincoln High School, on the other hand, does offer ELL programs as 16.4 percent of students are English Language Learners. Lowell does have a coordinator for the California English Language Development Test (CELDT). The test is intended to monitor the development of English learners’ English skills, and those who score high enough are identified to be potentially reclassified as English proficient.

When junior Raine Hu was in ninth grade, she immigrated to the United States from China. She went to Lincoln High School before transferring to Lowell as a sophomore. At Lincoln she took the ELL courses but was unhappy with the courses as they failed to teach her substantial English skills, she said. Instead, Hu learned English through reading, television, and talking to other students. Although she transferred out of Lincoln because she wanted a more rigorous academic environment, Hu felt that being at Lowell was completely different, as she was surrounded by native English speakers at almost all times. Hu said she feels comfortable at Lowell as she quickly became accustomed to taking regular classes.

Junior Yun Liu, who is Taiwanese, immigrated to America with her mother and brother in 2012 when she was in seventh grade. She had very limited English instruction prior to moving to San Francisco. She attended Everett Middle School where she received ELD (English Language Development) courses.

Because she attended a school with a low (five percent) Asian population, she was forced to speak English in order to communicate with others, and that was the main reason her English improved quickly, according to Liu. After a year, she felt that the ELD class wasn’t helpful anymore because she was being taught the same materials. As a result, she decided to transfer out of the ELD class because she felt she would learn more English in a regular class with native English speakers.

“I find in it a badge of honor somewhat, in that I’m accepted into mainstream American culture, but then again your individuality comes at the cost of it. It’s a double-edged sword.”

When Liu came to Lowell, she was placed in regular courses, as Lowell doesn’t offer separate ELL classes. During freshman year, Liu had difficulty in her history class because her teacher was speaking too quickly. When she asked him to speak slower, the teacher said he would, but the difference wasn’t enough for Liu, so the teacher advised her to get a tutor. Liu got a tutor but she still received a bad score, so the teacher pulled her out of class and said to her, “Why did you come to Lowell if your English is so bad?” according to Liu. She was surprised by her teacher’s direct words but felt that the teacher said it without thinking, so Liu was not extremely hurt.

The speed of his lectures was too fast for Liu to feel comfortable. “He spoke kind of fast for me, and he said he would slow down, but it was kind of like the same, so I felt like I had no help even if I asked,” Liu said. After the incident, she believed it would better for her to work alone. However she said she prefers to be in regular classes than ELL classes.

Pressures and mental health

Much of the pressure that Asian-American students face comes from traditional culture that their parents or family hold. Often in East Asian cultures, family is a person’s first priority. This expectation sometimes results in many students doing what will make their family happy instead of doing what they themselves want. “Being Asian, you’re taught that family comes first,” Truong said. “Growing up in America, you’re taught that the individual is just as important as the group. Growing up in this dual culture of East and West, it’s hard to explain to my parents that I’m not going to be this stereotypical Asian kid.”

He has mixed feelings about the model minority myth. “I find in it a badge of honor somewhat, in that I’m accepted into mainstream American culture, but then again your individuality comes at the cost of it,” Truong said. “It’s a double-edged sword.”

The cultural expectation of Asian-Americans is that Asians are academically smart, hard-working, self-reliant, submissive, obedient and are assumed to not need help, according to The Washington Post.

This unrealistic high standard for Asian-Americans creates a lot of pressure for Asian students, according to Jeung. As they measure themselves against the expectations of the model minority myth, Asian students may ultimately feel inadequate if they are unable to meet such expectations.

Jeung said that if Asians were quiet, they were assumed to lead problem-free lives. “Culturally, Asians may be more quiet, but that masks some of the educational needs that they have,” he said. “You might not recognize a learning disability. You may not recognize limited English language proficiency. You may not recognize mental health issues.”

Math teacher Robert Tran, a Lowell alum, said the model minority myth places unrealistic expectations and pressure to do well academically on Asian students in the classroom. “I have had students literally crying about getting a B,” he said.

In a competitive academic culture such as Lowell, Tran explained that many students and their parents believe they deserve an A, and so when students fail to receive the grade the students don’t know how to handle the situation.

“Though I may be generic in name or appearance, it is my interests, passions, and other traits that set me apart.”

Stereotypes, such as Asians are good at math, have also made some students feel as though they must live up to that. Tran recalls some students jokingly saying that since their peer is Asian, the Asian student is supposed to be good at math, even though he or she is struggling in the subject. “It definitely makes them feel bad,” he said. “You can see it in their face.”

Tran said much of the pressure comes from both parents and students themselves, who believe that getting a good grade is more important than the learning experience.

Sixty-five percent of Lowell’s Chinese students said parents pressure them to do well in school, according to The Lowell’s survey. However, Asian students are not the only ones who face parental pressure to do well. Seventy-seven percent of white students, as well as other ethnicities, agree that they face parental pressure.

“Alex” has also experienced immense pressure from Asian parents. Alex’s oldest sister attended UC Davis and later went to medical school.

His other sister, however, led a drastically different life. She got pregnant in high school, dropped out, and ran away to Mexico with her boyfriend. She came back after two years.

Alex took care of his five-year-old niece on a daily basis during freshman year, even during the summer, and then in later years, often watching over her and picking her up after school.

With the situation that his second oldest sister went through, Alex’s parents became increasingly strict about school. Every weekend, Alex would go to tutoring programs to help with his schoolwork.

He plans on attending UC Irvine, despite his parents’ disapproval of his decision, as they aspired for him to attend an Ivy League college. He said his parents pressure him so that they can compare their kids’ schools with their friends. “[My mom] wants me to succeed in life so she has bragging rights,” Alex said. “I never wanted to be a doctor. I’m majoring in science because I wanna make [my parents] proud. I feel like I have to make up for my sister’s mistakes. My whole family has my life planned out for me.”

Sometimes, this pressure can contribute to serious mental health issues which may be less likely to be addressed in Asian cultures.

Nationwide, Asian-Americans 18 or younger are less likely than whites, African-Americans, and Latinos to receive mental health support, according to New America Media. According to a national survey done by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2013, 29 percent of Asian-American high school students reported feeling “sad or hopeless” for at least two weeks in a row.

“At this point, he should be proud of me as long as I follow what I want to do, and have good intentions. I shouldn’t have to fit into his expectations.”

In his junior year, Truong was suffering from depression. “One of the issues was ‘Who am I supposed to be doing everything for? Myself or my family?’” Truong said. “I kept battling with myself over who I was as a person.” Truong eventually did seek help from the Wellness Center, friends and teachers, but he had to overcome the stigma behind mental health issues such as not seeking help initially, because he did not want to become a burden.

Seeking help

Truong believes that many Asian-American students refuse to seek help because they are afraid of bringing attention upon themselves.

This reluctance to seek help is also noted by Tran, who recalls how many Asian students are very closed about their stress. When he offers extensions on homework, his Asian students rarely reach out for help, even when they are facing lots of pressure.

At home, many students are unable to disclose their feelings and worries with their parents because of a fear of backlash and disconnection. Liu avoids opening up to her parents about her stress. “What they will tell me is the hardship they have [experienced] is not even close to [mine] and that I should know how to handle the stuff,” Liu said.

Alex too has difficulties opening up to his parents, because he believes that he will just be looked down upon by them. “I feel at times that I don’t feel loved,” he said. However, one person in his life that does support him is his oldest sister. “She’s more of a motherly figure than my own mom,” Alex said.

Wellness Center staff member Sarah Cargill said how different factors such as socioeconomic status, language barriers, citizenship status and cultural competency with health care providers make some in the Asian-American community reluctant to seek help. Some Asian communities may be more impacted by socio-economic barriers than others, Cargill said.

At Lowell, a sizable number of Asian students that do go to the Wellness Center and receive direct services such as counseling, groups, and clinic referrals. Forty-five percent of students who visit the Wellness Center identify as Asian, including Filipinos, according to data provided by the Wellness Center.

Despite what many think, this pressure can be managed.

Throughout elementary and middle school, Huang was pressured by his parents to do well in school. In high school, however, he began to take into account the importance of making his own choices rather than having his parents create his life for him. “My dad always wanted me to be a lawyer or a doctor,” Huang said. “In the beginning, it did affect me, because I would do things just to please him. At this point, he should be proud of me as long as I follow what I want to do, and have good intentions. I shouldn’t have to fit into his expectations.”

Sophomore Sheena Kanon Leong, who is of Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese descent, also realizes the importance of making her own choices rather than following what others want her to do. Leong mentioned how many of her friends take as many APs as they possibly can without thinking about the stress and pressure that comes with APs. However, she believes that the pressure at Lowell is related to the school’s competitive environment rather than race.

“I just go on my own pace,” Leong said. “I do sometimes feel kind of left out because in reg they are all taking these hard AP classes, and I’m just like ‘Oh, I’m in Modern World History.’”

Affirmative Action

The term “model minority” was first mentioned in a 1966 New York Times article “Success Story, Japanese American Style.” The article praised the success of Japanese-Americans while criticizing African-Americans, reflecting the idea pushed by Caucasians of the time that if Asians were thriving, then so could other minority groups.

For decades, Caucasians placed a spotlight on Asian-Americans as the model minority as a method of discouraging other minority groups, like African-Americans, from protesting, according to Ethnic Studies teacher Soo Park. These unfair comparisons disregard the discrimination other minority groups face.

Affirmative action in college admissions is a highly debated topic within the Asian-American community. It is meant to level the playing field for those who have been historically discriminated against in college admissions, for race or socioeconomic reasons. Supporters of affirmative action also claim that these measures increase diversity on campus. Opponents say that affirmative action sometimes disregards qualified applicants.

“I’ll rather push through myself and go through failure and all that than just to give up.”

However, affirmative action in some cases does help Asian-Americans, as many underrepresented Asian subgroups such as Cambodian, Laotian, and Burmese benefit from affirmative action. Some organizations, like the Chinese for Affirmative Action organization, believe that a holistic review helps disadvantaged Asians get into colleges and recognize the importance of affirmative action in diversifying the college’s community, according to Cynthia Choi, active executive director of the Chinese for Affirmative Action organization.

The University of California system does not use race-based affirmative action. This is as a result of California proposition 209, which was approved by voters in 1996 and prevents state government institutions from using sex or ethnicity for public employment, contracting, and education. In 2014, a bill to revoke California’s ban on using race on university admissions was challenged by over 20 Asian-American organizations, and the bill was ultimately dropped.

Some claim that private schools, such as Ivy Leagues, set a quota on Asian students. Thomas Espenshade and Alexandria Walton Radford of Princeton concluded in 2009 after studying data on admissions that Asian-Americans need 140 more SAT points out of 1,600 than whites to get a place at a private university.

Forty-three percent of Lowell Chinese students think that their ethnicity negatively influences their chances of college admissions, while 18 percent of white students agreed with the statement, according to the survey by The Lowell.

Truong, whose family is conservative, at one point believed that affirmative action was unfair towards Asian students, but after he researched more into the topic, his beliefs began to change. “I did believe that affirmative action unfairly grants people money that they do not deserve, until I looked a bit closer,” Truong said. “This is true for some cases, but in a lot of cases [affirmative action] also works. But I think we should tweak the system a bit to make it more fair.”

Senior Crizalyn Dela Rosa is concerned that the model minority myth will affect her chances for college admissions. Until the age of eight, she was raised by her grandmother, who immigrated from the Philippines.

Dela Rosa’s transition between middle school and high school was not easy. She attended James Denman Middle School where the environment and workload were less rigorous than Lowell’s, she said. Because she had not learned how to balance her academics with her personal life at Lowell, her GPA dropped drastically during her freshman year.

Throughout high school, she had to deal with personal family matters, including taking care of her two-year-old sister. She was unable to focus on her academics and extracurriculars as much as she wanted.

Despite all her struggles, her goal is to go to college. “I’ll rather push through myself and go through failure and all that than just to give up,” she said.

Dela Rosa identifies as a Pacific Islander, but she says that many people and colleges still consider Filipinos to be Asians. “I feel like if they looked at [Filipinos] as Pacific Islanders then I would have maybe a chance to have them view me differently,” she said.

The US Census classifies Filipinos as Asian. Both SFUSD’s and the California Department of Education, on the other hand, distinguish Filipino and Pacific Islander from Asian.

Dela Rosa believes that affirmative action is unfair towards her because if she is classified as Asian, colleges may be less likely to recognize her family circumstances. “What about the Asians that are struggling and they still want a life for themselves?” she said. “You’re not going to look at them because you just want to cut down on Asians?”

Lowell admissions

Lowell has also struggled in the past with the affirmative action debate.

In 1983, SFUSD implemented a race-based admissions policy as a result of the San Francisco NAACP v. San Francisco Unified School District ruling that the district was discriminating against African-American students.

This resulted in the now expired Consent Decree of 1983 to create more diversity at Lowell, which was predominantly Chinese-American.

In 1994, Ho v. San Francisco Unified School District case challenged the racial quotas used to limit the number of students of Chinese descent. As a result, SFUSD implemented a “diversity index” which excluded race from the quota system.

The current policy divides applicants into“bands” based off criteria such as current middle school, grades, test scores, socioeconomic status, score on the Lowell admissions exam, and special circumstances, such as coming from underrepresented schools.

Raising awareness

English teacher Samantha Yu wants to see change in the English curriculum in order to address and raise awareness on issues that can affect Asian-Americans. She believes that writing assignments focused on topics such as procrastination and depression and then sharing them with others who may relate to the content could help raise awareness about the issues. Yu wants to see actionable steps that students of all different backgrounds can relate to.

In some English classes, students read literature that covers the experiences that minorities in America face. One of these books include The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston, and describes the experience of a young Chinese-American woman with immigrant parents.

Last year, Park addressed the model minority myth in her Ethnic Studies class. Next year’s Ethnic Studies teacher Matthew Bell plans to continue to address important issues that minorities face in next year’s Ethnic Studies class by focusing on students’ personal experiences rather than teaching a narrative on the topic. “The Ethnic Studies course is meant to be empowering students to name their struggle, identify barriers, and listening to others,” Bell said.

Cynthia Leung, Yun Liu, Giping Huang, Tammie Tam, Tobi Kawanami and Ciara Kosai contributed reporting to this article. Special thanks to Debbie Lum.

Correction: The May 24 print edition version of this article did not include the fact that Yun Liu’s freshman year history teacher advised her to get a tutor and talked with her after she still received a bad score.

May 25 at 7:56 p.m. correction: A previous version stated that the purpose of the California English Language Development Test is to test students into regular classes. For clarification, the test is administered annually to measure the development of English learners’ English skill level and identify potential students to be reclassified as English proficient.

Note: This is an extended version of the article that appeared in the May 24 print edition.