Annie Huynh’s odyssey from classics student to teacher

In the bustling atmosphere of the hotel lobby, an excited 24-year-old Annie Huynh stood by the refreshments table. In the lobby, many men and several women mingled with one another, each wearing semi-formal attire. She was at a conference for classics, the study of ancient Greek and Roman literature in their original languages, and she had travelled out of San Francisco to attend. Her mind was filled, anticipating the intriguing lectures that were to come, including one entitled “Global Feminism and the Classics,” when an older white man approached her, telling her that something needed to be refilled. Huynh looked over at the refreshments table, then back at the man. The excitement drained out of her as she realized what the man had meant. He had thought she was a hotel staff member instead of a conference attendee.

That was the breaking point for Huynh, who had been pursuing a masters in classics up until then. Her experience at that conference made it clear that she would never feel like she belonged in the field of classics. Worn out from having to face the impacts of race and gender on her career, Huynh made the decision to stop pursuing classics beyond her masters. Although not doing classics in academia anymore, Huynh’s love for Latin motivated her to continue with the field as Lowell’s Latin teacher.

When Huynh first started learning Latin, she didn’t expect to like it. However, under the influence of an engaging teacher, she came to enjoy learning the language. “Going into Latin, I had this idea that, ‘It’s a dead language. It’s so stupid and it’s not useful,’ a lot of the sentiments that I know a lot of people have,” Huynh said. “And then, as I started learning Latin, I grew to appreciate the challenge of it.” According to Huynh, she loved Latin so much that, despite not taking Latin her last year of high school, she decided to pursue classics in college.

Her choice to do classics was not an easy one. Huynh had many interests, specifically in the arts. She applied to many art schools because of this, but her parents in particular were wary about her choice to go into either. “Everything I wanted to do was considered impractical by my parents,” Huynh said. “Art, fashion and costume design, classics — they’re not considered the most traditional route to getting a job after college.” In fact, when Huynh declared herself a classics major, she recalled her parents telling relatives and family friends that she was going to be a teacher.

Although she did end up as a high school teacher, Huynh’s original interest was in becoming a classics professor. According to Huynh, she was in a small classics program surrounded by welcoming people in her undergraduate studies, and it made her excited to continue on to graduate school. “I kind of went into this field with rose-colored glasses,” Huynh explained. “This entire ancient world had opened up to me, and I was very excited.”

I kind of went into this field with rose-colored glasses. This entire ancient world had opened up to me, and I was very excited.

— Annie Huynh

It was while she was pursuing her masters in classics when Huynh started to struggle with imposter syndrome. It was difficult to fit in as an Asian woman in a field dominated by white men, and there were no professors or students in her graduate classes who shared her experience. Huynh considered the people who had shaped her classics education, from her high school Latin teacher to her professors in graduate school, and found that they were all white and almost entirely male. “When you take a look at that and you finally actually get to think about it, you know that you don’t belong,” she said.

Despite believing in the importance of feminism and race conversations in classics, Huynh quickly began to feel as if people only saw her as being a woman of color when she felt she had much more to contribute to the discussion. “I started to realize that no matter what I did, I couldn’t escape having to talk about being a person of color in classics and I couldn’t escape feminism in classics,” Huynh said. “It became something that wasn’t for me and the research no longer became appealing or interesting, and it just didn’t turn into something that I wanted to continue to do or continue to fight. I was exhausted.”

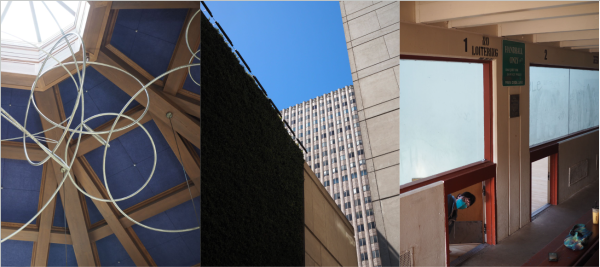

So, after completing her Masters of Art in classics, Huynh decided to go into teaching, and was hired as a Latin teacher at Lowell. On the first day of school in her first year teaching, she watched from her desk as her new freshman students walked in, their footsteps hesitant when they saw her at the front of the classroom. One student walked up to her and asked if he was in the Latin 1 class. Huynh was prepared. “This is Chinese,” she replied. After seeing the student’s expression, she laughed and added, “No you’re good — this is Latin 1.” Her seemingly nonchalant attitude betrayed her actual struggles with the transition. “My first year teaching, I was so nervous and anxious all the time that I would, after teaching, go home everyday and cry because I thought I was a complete failure,” Huynh admitted.

However, Huynh’s confidence in teaching grew with time. Now, in her third year teaching at Lowell, she always starts class with a friendly conversation before diving into Latin. She mentioned that teaching in a small program with few established resources was difficult because she had to put together tests, worksheets, and lessons for every language level on her own. However, she loves her students and designing curriculum. “I decided that I really liked teaching, and I just kind of fell into place,” Huynh said. “I love my job, and I wish that more people would give Latin a chance.”

I’m not saying there aren’t people of color in classics. There are also women in classics. It’s just that classics as of right now is a field that was not really designed for either of them.

— Annie Huynh

Though Huynh became a Latin teacher instead of a classics professor, she also didn’t give up the fight for inclusion in classics and Latin. She tackles racial inclusion in classics with discussions in class. During Black History Month this February, Huynh assigned two articles for her Latin students to read about the inherent white supremacy in classics, and how the classics community is attempting to deal with the problem. She then held a two-day discussion about white supremacy and classics with her students, hearing their input first before sharing her own opinion. Huynh still loves classics, but she also believes that it needs to become more inclusive. “I’m not saying there aren’t people of color in classics,” Huynh explained. “There are also women in classics. It’s just that classics as of right now is a field that was not really designed for either of them. But there are groups of people who are working to support these minorities in classics, so the field is slowly being diversified.”

Huynh’s career path has taken several turns, but she’s grateful for the experiences each one has given her. “I have my BA in classics and my MA in classics, but I never thought that I would end up as a high school teacher,” Huynh said. “I don’t regret pursuing classics in academia, but now I think teaching Latin to the students I have is great, too.”