Lowell admissions proposal for the 2021-22 school year divides San Francisco

Last Tuesday afternoon, hundreds of parents, students, and alumni hopped onto SFUSD’s Board of Education (BOE)’s Committee of the Whole Zoom meeting, ready to share their thoughts on a proposed policy that would make admission into Lowell for the coming school year a lottery. The event was filled with passionate interruptions and name-calling throughout, and text campaigns and social media rants afterwards.

Tensions are running high around the proposed policy and opinions are divided. Some are concerned about the process used to propose the policy in the first place, rising high schoolers and parents are worried about their chances of getting into Lowell, and still others are disturbed by the inequities in the current system. Many even anticipate that this policy, while only proposed for one year, could spur on the end of all merit-based admissions at Lowell, opening up a whole new debate and range of opinions.

The proposal was officially announced at 4:30 p.m. on Oct. 9 as a press release. Governor Gavin Newsom’s decision to cancel SBAC administrations and the BOE’s decision to make Spring 2020 grades Credit/No Credit due to COVID-19 make the existing admissions system unusable, according to the press release. If the policy is passed, Lowell’s freshman admissions for the 2021-2022 school year would follow the ranked-choice lottery guidelines of Board Policy 5101 like almost all other SFUSD high schools. This would give students with siblings in their preferred schools first priority, graduates of Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School second priority, students living in census tracts with the lowest average test scores third priority, and everyone else last priority. In addition, transfer applicants would not be accepted that year. On Oct. 13, four days after its announcement, the BOE held a Committee of the Whole meeting and opened the floor for community members to speak on the matter, giving the support and opposition sides half an hour each. The BOE plans to vote on the measure during an upcoming board meeting later today.

One of the biggest issues people have found with the policy does not have to do with the policy itself but rather the way it was proposed and how the BOE has been handling the situation. Multiple community members have criticized the timeline of the announcement as being rushed. In a statement released Oct. 19, the Lowell Parent Teacher Student Association called out the BOE for “[attempting] to bypass any meaningful conversation about Lowell’s admissions policy with the students, teachers, administrators, and parents it will affect the most” by “introducing the topic by press release on a Friday afternoon leading into a 3-day weekend” only 11 days before a vote. The statement further criticized the BOE for giving only four days’ notice to community members about the meeting for public comment.

In response to these complaints, Commissioner Rachel Norton explained the district’s timing is a result of the workload that the pandemic has brought on. “There’s been a lot going on, and people are tired,” she said. “I’m sorry, I don’t think this was the most urgent problem that we needed the staff to solve over the last six months.”

The reasoning for a lottery was also influenced by this limited time frame, as Assistant Superintendent Bill Sanderson, an author of the policy, explained in the Zoom meeting. He said that they had chosen to propose the lottery system due to the fact that it already existed, and so they would not need to take more time and build new infrastructure.

“Most Board members appeared to regard the ‘public comment’ as a nuisance, having already made up their minds,

— the Lowell PTSA

However, much of the community isn’t satisfied with this reasoning. Seeyew Mo, who created a change.org petition urging the BOE to consider alternative admissions systems and include more community input, is among those unsatisfied with these explanations. He wishes that Sanderson had given the community more information at the Committee of the Whole Zoom meeting and listed specific pros and cons regarding time and infrastructure for each option considered. Mo believes the BOE ought to do a better job and “consider all the options, evaluate the pros and cons, and pick the best decision out of all the alternatives.” He feels that adequately weighing all options is “how you make a decision that affects students.”

Many other community members and even a Board member agree that the district’s reasoning for the policy was unclear and did not allow for enough community voice. “I am not at all okay with the process that was put forward. I really feel that this process has shut folks out,” Commissioner Jenny Lam said.

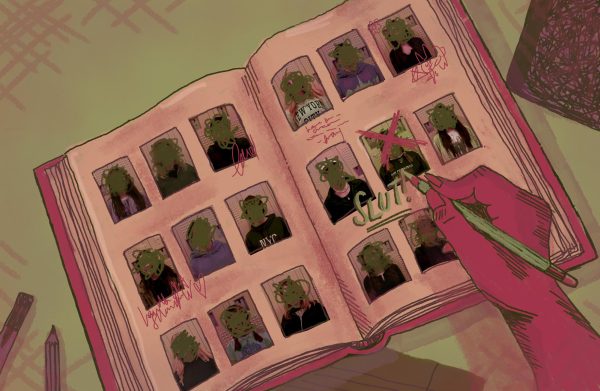

The Lowell PTSA further feels that not only did the Board “[fail] to engage with the Lowell community in the discussion,” but it also handled the little community discussion they did engage in in a dismissive, inadequate way. “Most Board members appeared to regard the ‘public comment’ as a nuisance, having already made up their minds,” they wrote in an official statement. “When the Board describes Lowell as a ‘sacred cow’ and people who disagree with them as ‘bunch of racists,’ it cuts off all meaningful conversation, and flies in the face of inclusivity.” They also expressed that the Board “[set] up a divisive dialogue” with public comment set up so that commenters first had to pick a side of the issue and then the two sides had 30 minutes each to speak.

Reciprocal concerns were expressed by the BOE. Board members felt that numerous statements from people opposed to the policy about Lowell’s supposed superiority as a selective high school were disheartening, especially to students not attending Lowell. To Commissioner Alison Collins, they brought on the assumption that students who do not attend Lowell are “doomed,” “lazy,” “violent,” or “substandard.”

Why did our school district suddenly decide that pre-COVID academic work is not valid?

— Emily Murase

In addition to the various concerns about the district’s timing and process, those who support a merit-based admissions system have pointed out multiple other options that would allow Lowell admissions to remain selective. In fact, many parents during public comment brought up alternatives to the lottery, and over 8,200 people have signed Mo’s change.org petition calling for the BOE to clearly show that they have exhausted those alternatives already.

Some prominent San Franciscan figures support alternatives like using grades from the first semester of 7th grade and 6th grade, along with the essay and extracurricular components of the application, none of which were be affected by COVID-19. This would allow Lowell to keep its selective admissions despite not having second semester 7th grade grades or standardized test scores. “I would really urge the district to at least—at a minimum—stick with the data that we do have,” California State Assemblymember Phil Ting said during Tuesday’s meeting. “It’s not entirely fair for the students who have been preparing for years, frankly.” Former BOE President Emily Murase also supports this option, writing in a Facebook post, “Why did our school district suddenly decide that pre-COVID academic work is not valid?” BOE Student Delegate and Lowell senior Shavonne Hines-Foster supports the use of an essay to determine admission and further believes they should be graded on message, not grammar or quality of writing.

Many believe that the district has not adequately considered these alternate options for Lowell admissions and instead see this policy as the BOE using COVID-19 as an excuse to eliminate Lowell’s merit-based admissions for good. They point to multiple BOE members having supported elimination of the selective Lowell admissions in the past and its history of being a highly debated topic. “[The decision to implement lottery admissions] has nothing to do with COVID. It’s clearly political, right? It’s sneaky,” one community member said during the public comment period of the BOE meeting.

Among those who have the most at stake if the BOE doesn’t consider other options are the current 8th graders looking to apply to Lowell. Hailey Huang, an 8th grader at AP Giannini Middle School has been working hard to keep her grades up in hopes of attending Lowell and was worried by the news of the policy. “My first thought was ‘Will I be able to get [into Lowell] this way? Will [getting in] be easier or will it be harder?’” she said. Lowell was previously her first choice school, but Huang is now considering private schools more seriously, preferring their merit-based admissions because they would allow her to earn a seat based on her work.

During Tuesday’s public comment section, other 8th graders also expressed frustration that their years of hard work might not be rewarded. “We’ve been working very hard for the past three years to just meet the application requirements,” said Aiden, an 8th grader at Alice Fong Yu Alternative School. “All our work has pretty much gone up in smoke.” Oscar, an 8th grader at Roosevelt Middle School, feels that the district could find a better alternative. “I think that SFUSD can take the steps to make sure that equity happens at Lowell by phasing in a new system without hurting today’s 8th graders, like me and my friends,” he said.

When we talk about merit, meritocracy, and especially meritocracy based on standardized testing…those are racist systems,

— Alison Collins

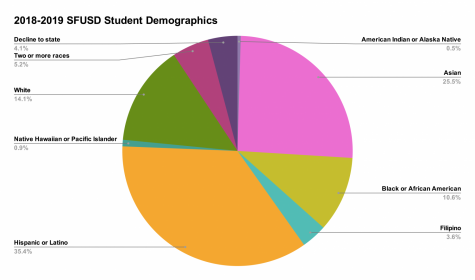

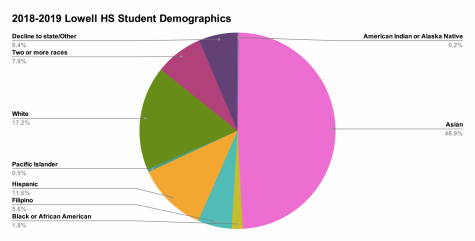

On the opposite end of the public opinion spectrum, many support the proposed change in Lowell’s admissions policy because they see the current Lowell admissions system as racist, classist, and inequitable. They anticipate a freshman class more representative of San Francisco under the lottery system, something Lowell’s 54.5 percent Asian and 17.2 percent White population during the 2018-2019 school year doesn’t quite achieve compared to SFUSD’s overall 25.5 percent Asian and 14.1 percent White population. Additionally, the 1.8 percent Black and 11.6 percent Hispanic population at Lowell is much lower than SFUSD’s overall 10.6 percent Black and 35.4 percent Hispanic population, something many attribute to the merit-based admissions system. “When we talk about merit, meritocracy, and especially meritocracy based on standardized testing… those are racist systems,” said Collins, explaining why she doesn’t support the current meritocratic admissions. Additionally, wealthier students tend to score higher on standardized tests. For example, the median SAT score increases with family income. Other factors, like parental education and native language have also been shown to correlate with performance on those tests. Most of the people who see Lowell’s meritocracy as inherently racist advocate for the permanent implementation of the lottery system in order to address these diversity and equality issues, beyond the one-year policy proposed by the BOE.

Others take a less absolute stance. Melissa Bowen, a parent of a Lowell freshman, doesn’t completely advocate for the lottery but still agrees that the current system has inequities that need to be fixed. She criticizes fellow parents definitively opposed to the policy, writing, “It’s really natural to want the best for our own kids, but it’s worth thinking about what’s really going on before committing oneself to advocating for the maintenance of a bad system and then being surprised when people are not sympathetic.”

Even among those pushing for more diversity at Lowell, however, there is disagreement as to how effective a lottery system would be at solving these issues. Some believe that a lottery may just be a first step to solving these issues, as the problem with diversity may run deeper. “When I’m helping [Black and Latinx] kids from Everett Middle School go over their Lowell applications, they’re like, ‘Y’know, my mom doesn’t really want me to go here because of all the racism they talk about,’” Hines-Foster said. Because of Lowell’s culture, Virginia Marshall, the president of the SF Alliance of Black School Educators, didn’t want her daughter, now a student at Phillip and Sala Burton Academic High School, to go to Lowell, despite a middle school teacher’s encouragement. “I want her to have a well rounded education, and she will not get that at Lowell, socially. She will be an outcast,” she said. Marshall hopes that with a lottery, more Black and Latinx students will have the opportunity to go to Lowell and eventually create a more accepting community for those students.

Others believe the lottery system might even have the potential to exacerbate the representation problems at Lowell. Lowell Alumni Association President John Trasviña mentioned in his official statement about Lowell admissions that the BOE has acknowledged that their lottery “actually exacerbates racial segregation.” He cited the BOE’s 2018 decision to phase out the system in an attempt to make school assignments more predictable and schools less segregated. Additionally, there are concerns that if White and Asian students bring their siblings, who are currently given preference under the lottery system, it could limit the number of underrepresented students being admitted. “If we’re going for a system that’s truly random and equitable, we should not have a sibling preference or geographic preference,” a community member said during Tuesday’s meeting.

With the stakes set high, many are anticipating the BOE’s decision this afternoon at their meeting, which will also have a time slot for public comment. And while opinions on the policy differ drastically, some community members from various sides are coming together to call for a more respectful dialogue, in order to avoid a repeat of the previous meeting. “We owe it to our students to model behavior that emphasizes collaboration and respectful dialogue, especially when we disagree,” the Lowell PTSA wrote. They also called on the Board to actively foster a sincere discussion and not immediately dismiss those who don’t agree, referring to the Board’s behavior in the previous meeting. “We are better than this, and our elected leaders need to be better than this.” Mo agrees and asks that both sides make an effort in future discussions, for the sake of the students. “I just really hope that people don’t break each other… [Let’s] try to have an honest discussion whichever side you’re coming from,” Mo said. “I think that’s only fair for the students.”

Lily • Jan 24, 2021 at 6:04 pm

Merit-based admission to Lowell is NOT racist or class-exclusive. Lowell has been a school to help understand privilege kids based on their hard work. However Lottery is telling kids there is no difference between hard work and laziness. Liberals is destroying the fundamentals values.

Tom • Nov 15, 2020 at 12:36 pm

Great piece of journalism. BRAVO LADIES

eNyese Joshua • Oct 27, 2020 at 10:40 pm

I’m praying Lowell moves to this idea of the lottery. FANTASTIC IDEA!!!!!

John Yelding-Sloan • Oct 25, 2020 at 10:00 am

Easily the best discussion of this issue I’ve read. The world needs journalists! Well done, Lowellites!

-John Yelding-Sloan

Lowell ‘85

Brooke Anderson • Oct 25, 2020 at 7:59 am

A thorough article on an important issue (from a Lowell alumnus who works as a journalist).

Simon Tan • Oct 24, 2020 at 12:57 pm

Excellent piece of journalism – finally a well researched and balanced take on the admissions issue.

Kudos to the staff – you’ve made us alumni proud.

— Simon Tan

Lowell alumni class of ’04

Rex Bell • Oct 21, 2020 at 5:01 pm

I’m very upset about the BOE decision. They jammed this change through without adequately considering alternatives. I feel especially bad for those students who have dedicated years of hard work to get into Lowell in 2021. For many, their hopes and aspirations are brushed aside. Merit-based admission to Lowell is NOT racist or class-exclusive. I know a of a young student from an underprivileged background, raised by a single mother who’s desire to attend Lowell caused him to focus, apply himself, and finally succeed. This taught him valuable lessons of discipline and perseverance that have carried him though life. That young student was me.

Please stay strong, adaptive, and strive to maintain Lowell’s proud tradition.

Rex Bell

Class of ’74