Navigating collegiate sports and recruiting during the pandemic

In a typical fall semester, sports at all levels would be underway. Throughout the West Coast, crowds would be gathering in high school gymnasiums and college stadiums, enthusiastically rooting for their favorite teams and participants. But not this year.

While some states are allowing athletic seasons to proceed as normal, the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF), the governing body for high school sports in California, chose to postpone fall sports. As some of San Francisco’s most iconic structures such as Kezar Stadium lay empty, Lowell’s student-athletes find themselves stuck at home, not knowing of their future in athletics. And some recent Lowell grads are in college unable to play the sports for which they were recruited.

Not being able to participate in a sports season has had implications beyond the games themselves. For student athletes seriously involved in recruiting, the process where a college coach scouts and encourages an athlete to join their team (usually using scholarships as incentives), they are denied opportunities to further dazzle college coaches with their performances in hopes of solidifying a scholarship, or chances to visit schools to help determine where they can best thrive athletically. However, even those who currently play for a college’s athletic team are unable to pursue their sports at a more competitive level, as some collegiate sport seasons across the country have been postponed or cancelled.

According to cross country coach Andy Leong, the biggest obstacle high school athletes, specifically California athletes, face is not being able to display their improvement to college coaches. Citing a few of his own runners, Leong emphasized the difficulty the postponed season has had on athletes who were primed to have breakout performances during the fall. Unable to showcase the growth that could propel them to the next level because of CIF’s strict guidelines, they can only be hopeful for an opportunity to play next semester.

Junior cross country runner Jenna Satovsky has been recruited by multiple schools since sophomore year, after college coaches took notice of the times she posted. Entering this school year, Satovsky was looking forward to talking more with coaches and gaining more results for her to market. Instead, she finds herself being unable to race and present the concrete results college coaches want. While there are alternatives to races, such as time trials, where the runner is recorded running a certain distance in an isolated circumstance, Satovsky says they don’t carry the same weight a race would. This poses a major disadvantage to athletes in states where stricter guidelines have prohibited seasons from occurring. “It’s a lot harder to push yourself in a time trial than it would be in an actual race,” Satovsky said, “I know there are people across the country who are having seasons currently, [so] I hope they will be respectful and considerate of those of us who haven’t been able to.”

Similar to Satvosky, senior varsity girls volleyball player Gabriella Quach became involved with recruiting as a sophomore. She started by creating montages of her performances and emailing them to coaches over the summer. When her junior year began, Quach managed to visit a few college campuses and chat with coaches. During the spring semester, Quach was set to participate in a national tournament with her club team, offering her a platform to exhibit her skills to coaches from around the country and an advantage when she would start applying to colleges. But, unfortunately for Quach, the tournament was canceled because of the pandemic, leaving her disappointed and scrambling for a way to stand out as an applicant.

The interactions Quach can have with coaches is hampered without a season. Having no games to play limits the amount of performances for coaches to evaluate Quach’s skills. “It’s competitive gameplay for [coaches] to see how I’ve grown as a player since the last time they got to see me play,” she said.

Satovsky admits that not knowing when she can gain results for coaches to assess has caused her to lose confidence about her recruitment. Skeptical about a season occurring this school year, she is unsure about what steps she should take to help her appeal to college coaches. “I don’t want to have my hopes up because everything recently has been unexpected, so I’m not going to set the expectation for myself to be let down,” she said.

A position on a college team’s roster is not guaranteed for Satovsky or Quach, and both athletes face losses if they aren’t offered a roster spot. Quach’s odds of making a team would be slimmer if she has to try-out after enrolling at a school as most of the roster would already have been determined, and Satovsky could lose the ability to run competitively in the National College Athletic Association (NCAA) altogether. Nonetheless, both athletes continue to hope for the best.

College sports haven’t escaped the grasps of COVID-19 either. Some athletes received plans from their schools’ athletic departments in a swift manner, while other athletes awaited on edge.

2020 Lowell graduate Hannah McCord, who was recruited to play women’s soccer at the University of Portland faced such a predicament. After weeks of anxiously checking Twitter for updates in her dorm, Mccord finally learned during a tear-filled Zoom call with her coaches that her season would be postponed during the fall, with only a narrow possibility of playing in the spring.

McCord admitted being unable to competitively play the sport she loves since March has been hard, and longs for gameplay. “I miss playing in general, scoring goals, [and] cheering each other on,” she said. “I miss every aspect of the sport.” She had come into her freshman season with a goal of immediately proving to her coaches that she deserves plentiful playing time. But now that her season is postponed, McCord is training in anticipation of playing early next year. Under NCAA and local guidelines, McCord and her team are allowed to train together.

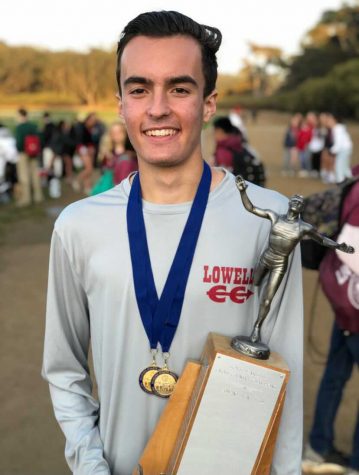

Not all collegiate athletes are as fortunate, however. Zachary Parker, Lowell class of 2020, was recruited to run cross country at the University of California Santa Barbara. Parker’s beginnings with the team have been limited, saying he hasn’t had anything more than voluntary workouts given by coaches. Parker said that meeting his entire team was something he’d been looking forward to, but he has met only a few of his teammates thus far. “I was hoping to have a good team atmosphere,” he said.

Despite these hurdles, both Parker and McCord have found support from their teammates and parents. McCord described how her teammates have checked in with her often, despite not being too familiar with her. Parker explained how although he only has met a few of his teammates, he appreciates the limited company they have provided.

While the process has been emotionally draining for McCord and Parker, both are understanding of the choices made by the authorities of college sports. “These are incredibly unprecedented times and nobody is going to make the perfect decision,” McCord said. Parker echoed McCord’s sentiment: “I think [the NCAA] is doing about as well as they could.”

Even as the outlook of college sports looks fuzzy and recruiting has been muddled without matches for coaches to scout, Quach and Satovsky continue to find optimism in their situations ahead. Quach is willing to embrace the stakes, confident she will be able to work for a spot on the team of the college she ends up attending. Satovsky is hopeful, yet flexible, explaining that while she would love to run as an NCAA athlete, she is open to exploring other options for running in college. “I’ll probably end up joining a [running club] at the school I end up going to if I’m not able to make it to the team,” she said.

Although their immediate future may appear bleak, student athletes remain resilient, continuing to train in anticipation of playing in the spring. “Mentally, I have to believe that I have a season. It gives me something to look forward to and work towards,” McCord said. “I really just want the freshman soccer season that I hoped for.”