On the sidelines: How Lowell students deal with injuries

Junior Sarah Ginsburg strikes the ball at the opponent’s goal.

“We were doing some one-on-one drills and I just pivoted and the next thing I knew I heard my leg snap,” junior winger Sarah Ginsburg said. Sprawled on the green field, Ginsburg couldn’t get up. All she could do was look at her leg which “looked kind of out of place,” and was later diagnosed as a tibial plateau fracture, a break in the top of her shinbone.

Every year, athletes at Lowell are injured. These range from minor sprains and muscle strains, to more severe injuries such as Ginsburg’s. There are systems in place for these injured players to get assistance and physical therapy at Lowell.

Ginsberg was injured over two thousand miles away from home while attending a soccer camp in Chicago in May. According to Ginsberg, college coaches were there scouting, and she had felt a lot of pressure to do well. Her parents flew out to be there for the surgery and accompanied Ginsburg back to San Francisco. “I was in a wheelchair and my dad had to argue with the flight attendants to get me more room on the plane,” Ginsburg said.

In the months that followed, Ginsberg started on the long road to recovery. Ginsburg went to physical therapy to help prepare her for her return to soccer. One of the exercises she focused on was weight training. “[Weight training is] preventative, making sure that I’m strong enough so that when I play the injury doesn’t happen again,” she said. While doing her physical therapy, Ginsburg still had to balance academic obligations. “I still had almost zero mobility and that was the time where I had my finals and AP testing so I had to work around that,” she said.

Ginsburg’s hard work allowed her to recover strongly from the broken leg and get out on the field again. Even now she is still careful to make sure she doesn’t get injured again. “I don’t push it if something feels off, and I stretch before the games and the practices,” she said. These are changes from her earlier training style. Before her injury, Ginsburg did no injury prevention and didn’t think that stretching was important.

Junior Sarah Ginsburg dribbles the ball up field.

Though Ginsberg had recovered from her broken leg by the start of Lowell’s winter soccer season, she was still unable to play until January. She had a torn muscle in her hip because she put too much pressure on it when her leg broke. In addition to Ginsburg, several other players were also out at the beginning of the season. “We had five or six injuries so it really impacted who we could play and who we could start,” Ginsburg said. The multitude of injuries also affected team chemistry. “It was difficult to only have a portion of our players play, and when they started slowly coming back we had to integrate them into the team so we could regain that chemistry,” she said.

Though Ginsburg was able to return to playing by the next season, other athletes, like senior Luxi Arnold who tore her ACL freshman year, had a longer road to recovery. Arnold tore her anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in her freshman year during tryouts for the soccer team. After being assessed, Biviano told her that she had probably torn her ACL and would need surgery if she wanted to return to sports. “I was definitely terrified,” Arnold said. “I had broken bones before and stuff like that, but I had never had something this bad. I had never had surgery.”

Arnold missed the last day of finals because of her surgery and spent all of winter break on bed rest. “I couldn’t take the brace off and it was left in extension the whole time and I was on crutches,” said Arnold. “About a month later I was allowed to turn it and let my brace actually turn into flexion to allow me to kind of move my leg when I had brace on.”

Arnold’s recovery continued after surgery, and even several years after her surgery she still has to remember to be careful with her knee while playing sports. “[Physical Therapy] lasted about a year after doing squats, lunges, a lot of redevelopment of muscle strengthening to kind of prevent my knee,” she said. “Muscle strengthening was something that became really relevant to me because muscles basically coat and surround the structure like your ACL and can prevent your from even tearing it in the first place.” One such precaution is a knee brace, which is supposed to help with stability and prevent another tear. It was around two to three years before she could get back to any sense of normalcy. Though she worked hard at physical therapy, Arnold hasn’t played soccer since.

Though her recovery process was difficult, Arnold was supported by Athletic Trainer Gina Biviano. According to Arnold, it was difficult to no longer play the sport that she had been playing since Kindergarten. “I think watching your friends play without you is the hardest part,” she said. During this time, Arnold was supported by Biviano. Though Biviano helps the athletes recover physically, she also tries to help them get into the right mindset so they can make a full recovery. “I try to address the mental aspect for the injured person, [because they do not] have the identity of being an athlete for a short time,” Biviano said. Biviano does this by speaking from her own experiences as an athlete and will sometimes introduce the injured student to another person who had the same injury.

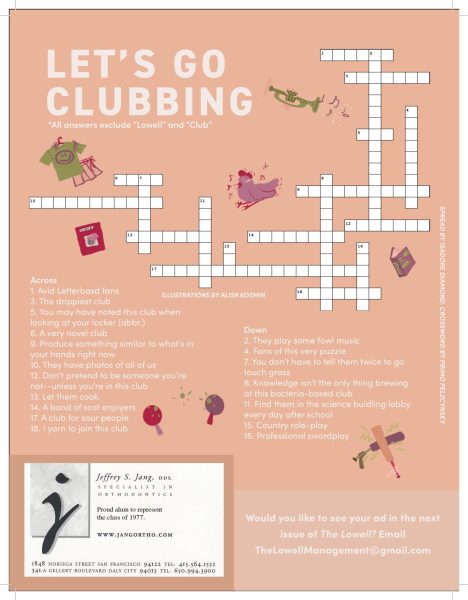

While recovering, Arnold found a community in the Sports Medicine Club, which Biviano sponsors. The club gave her an opportunity to meet and support other people who had gone through similar injuries. “What the club does is really kind of inspiring and powerful to the athletic community,” she said. “I do have friends now who have torn [their ACL as well]. I get to go through that process with them and be there as an advisor and somebody who’s been through it, kind of ease them along the same thing.” For Arnold, the club was a way to stay connected to the community she grew up in, despite her injury. “With sports medicine you can be with athletes again and specifically athletic trainers. You get to be on the field with the athletes and really be a part of that team and watch something that you love.”

According to Biviano, members of the club have not only learned more about potential careers in sports medicine, but they have also been taught some basic skills, like wrapping wrists or adjusting a crutch. Some club members like Arnold, who is now president of the club, have also had the chance to help Biviano on the sidelines of games.“We get to help [Biviano] in any way she tells us to help the player off the field,” Arnold said. “We might act like a crutch or after [they’re off] the field we’ll help them get what they need.”

One issue that Biviano teaches coaches about is injury prevention. For soccer players, the most common type of injury prevention is to prevent ACL tears. These drills can also be used as a warm up as the exercises strengthen leg muscles and teach the players how to jump and land safely. Though these exercises can help, several factors prevent them from being entirely effective. “The difficulty with prevention programs is that they take time, typically away from practice, and you have to do them consistently to see results,” Biviano said. “You can’t just do them once a week and hope that your muscles will remember.” Despite the difficulties, Biviano still encourages all coaches to do whatever injury prevention they can, and to try and go to the weight room when possible to strengthen muscle.

Though steps can be taken to reduce the risk of injuries, injuries still happen. “There’s an inherent risk of injury in any sport,” Biviano said. Ginsburg has seen this up close while playing soccer. “It’s a sport with a lot of contact so you never know what could happen,” she said. Despite this, hundreds of athletes at Lowell join sports teams every year and compete for a championship title. But with every title comes more players limping into Bivano’s office with hope to get back out on the field.