The elusive quest: Lowell’s struggle to achieve racial equity

Four years after the BSU staged a walkout to protest the unwelcoming climate for African American students at Lowell, the school is still grappling with how to create a more inclusive environment for minority-group students.

“I don’t see why I can’t use N—-.”

Senior Stephanie Duru, a member of the Black Student Union (BSU), was chatting with friends during her AP Computer Science class last semester when she overheard this comment coming from a group of Asian and Caucasian boys in the class. The boys were discussing if they should be allowed to use the “N-word.” Upset over their use of the slur, Duru approached the boys and told them that no one should use the “N-word,” regardless of their race. The boy leading the discussion looked confused, and said to Duru, “There are such things as freedom of speech.”

It is racially insensitive instances like this that Lowell has been trying to address and curb through monthly two-hour equity-centered professional development meetings since the start of the 2016-17 school year. The aim of these faculty-focused trainings is to make Lowell a more inclusive and culturally sensitive environment so that minority-group students like Duru can have a more positive and comfortable experience.

The issue of inclusiveness boiled to the fore for the Lowell administration four years ago, according to senior and BSU co-president Ediana Berhane. With BSU members already weary from experiencing an abundance of microaggressions and racist comments, the group was incited to stage a walkout in February 2016 following a fellow student posting a racially offensive collage on the windows of Lowell’s library.

The walkout to protest Lowell’s unsettling racial climate culminated at San Francisco City Hall, where members of the BSU presented to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors a list of demands they believed would improve the experiences of African American students at Lowell. One of these demands called for Lowell teachers to be required to participate in a cultural sensitivity program, prompting the implementation of the equity trainings.

Now, three and a half years into the trainings and with more than $358,000 spent by Lowell and the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) in fees to the nonprofit consulting firm hired to facilitate the meetings, many Lowell stakeholders feel that far too little progress has been made and much more work needs to be done, including creating opportunities to educate students to be more mindful of their behavior.

“I feel like I’m having the same experience just in a different grade,” Duru, who has acted as a student facilitator during the equity trainings since the 2017-18 school year, said of the progress that has been made.

In fact, Duru says her participation at the meetings has made her experience at Lowell more difficult at times. She explains that after pointing out instances of microaggressions or implicit bias and offering ways to address these issues, she would later be singled out in the classroom by her teachers who attended the meetings where she spoke. Following making the same type of comment that Duru explicitly discussed and discouraged, they would say, “‘Oops, sorry! This offends Stephanie,’” Duru said.

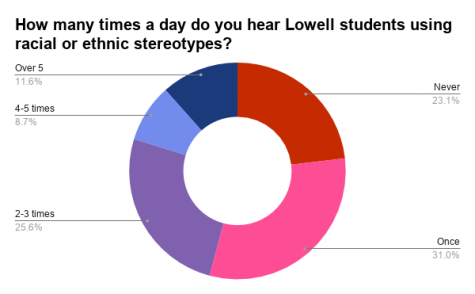

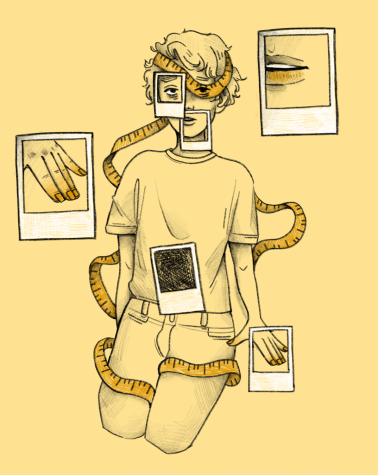

More than 45 percent of student respondents hear their peers using racial or ethnic stereotypes at least two times a day (Data from a random survey of 246 students conducted by The Lowell in March 2020).

The lack of significant forward movement is also evident quantitatively when comparing the results of a survey conducted by The Lowell and the Lowell Data Club in February 2016 with the results of a student survey conducted by The Lowell in March 2020. The February 2016 survey found that more than 30 percent of the student respondents heard people using racial or ethnic stereotypes about once a day, and more than 25 percent reported hearing such stereotypes many times a day. The March 2020 survey found that more than 30 percent of the student respondents hear their peers using racial or ethnic stereotypes about once a day and more than 20 percent hear such stereotypes at least four times a day.

While assistant principal Orlando Beltran acknowledges that Lowell has a long way to go toward providing an inclusive environment for minority groups, he also believes the trainings have been successful in increasing awareness among teachers of the prevalence of microaggressions and implicit bias. “[The trainings] have brought a lot of stuff to light,” he said. “But I think a lot of it still exists and I think that affects teachers, it affects staff members and students.”

English teacher Nicole Henares also acknowledges the struggle facing Lowell. “We have huge issues with equity,” she said. “We have huge issues with learning how to be inclusive, but the inclusion begins with us [teachers].”

However, Henares says participating in the monthly trainings has been beneficial. For example, using a protocol focused on improving listening behavior has brought more inclusion into her classroom.

I feel like I’m having the same experience just in a different grade.

— Stephanie Duru

While Beltran and Henares have found positive outcomes regarding the monthly trainings, many other faculty members expressed feelings of disconcertion over the trainings, particularly because of the style and approach of the San Francisco Coalition of Essential Small Schools (SF-CESS), the organization hired to facilitate the meetings. “When [SF-CESS] walked in, it felt very punitive instead of enriching,” ethnic studies teacher Lauretta Komlos said. “I think had it felt like an educational program or professional development instead of a punishment, it might’ve been better received.”

Science teacher Catherine Christensen concurs, saying that SF-CESS seemed to be operating under the misconception that most teachers were coming into the meetings without any previous experience teaching at underfunded schools or schools with large African American and Latino student populations. “They assumed because we’re at this school, we’ve had no other experiences, which was wrong because most teachers who are here have been to many other schools,” she said. “[SF-CESS] didn’t look at what our experiences were and what’s really going on in our classrooms. They were kind of pointing the finger at us.”

The implementation of small-group trainings, called “iGroup” meetings, was an additional source of frustration for some faculty members, including AP Physics teacher Scott Dickerman. Dickerman, who disagrees with the overall premise of the meetings, which he labels “ideological indoctrination,” says his opinion was solidified at the second iGroup meeting in which he participated.

During this meeting, Dickerman and other teachers were instructed to discuss a cartoon’s depictions of “equality,” “equity,” and “liberation.” The first section of the cartoon illustrated “equality,” showing three boys, regardless of height, standing on three equally sized boxes, attempting to look over the fence to watch a baseball game. The second section illustrated “equity,” showing the same three boys, but the shortest boy was given three boxes to stand on so he could see over the fence. The last section illustrated “liberation,” showing the fence knocked down, and the three boys watching the baseball game uninhibited.

Many teachers were displeased by the approach and methods used by SF-CESS to facilitate the equity trainings.

From Dickerman’s point of view, SF-CESS’ use of the word “liberation,” a term often associated with neo-Marxism, demonstrates that a politicized ideology was being promoted rather than a practical pedagogical solution. “When I saw the word ‘liberation’ that said to me, ‘This is ideological,’ and I cannot take it seriously and I will not take it seriously,” he said.

Another significant point of contention for Dickerman and other teachers was the restrictive nature of the trainings. Each iGroup meeting was required to start with an activity to review the “norms,” a set of guidelines and rules established by SF-CESS for how the trainings were to unfold, according to Dickerman. These norms included “go to the source” when a conflict arises and “speak your truth.” Dickerman saw the norms process as “an insult to our intelligence,” recalling one review activity in which the SF-CESS facilitator instructed faculty members to explain information to their peers as if they were five years old. That was the breaking point for Dickerman and from then on, he would leave during the norms reviews and return when they were completed.

One of the norms that teachers’ Union Building Committee (UBC) representative and AP Environmental Science teacher Katherine Melvin had the biggest issue with was “expect and accept non-closure.” “One of their standards was that we needed to accept non-closure and that was a problem because I’m a teacher,” she said. “Speaking for myself, if you point out that there’s a problem, I want to fix it. I don’t want someone to tell me that there’s no fix.”

For Melvin, the norms review activities exemplified the confining nature of SF-CESS meetings, and what hindered their potential for effectiveness. “Because SF-CESS’ structures were so strict and stringent, some [faculty] members just felt that they lost their voices completely,” she said.

Melvin felt this way herself at times. At one iGroup meeting in which teachers were instructed to respond to a prompt, as Melvin answered the prompt, the SF-CESS facilitator corrected her word usage to be more in line with protocols. “She was rewriting my sentence as I was talking, which is a very difficult way to communicate and very, very frustrating,” Melvin said.

Because SF-CESS’ structures were so strict and stringent, some [faculty] members just felt that they lost their voices completely.

— Katherine Melvin

What was even more problematic than the restrictive and controlling nature of the meetings for Melvin and other teachers, was that SF-CESS never outlined an objective for the program. “They never had a goal,” Melvin said.

Komlos echoes Melvin’s sentiment, noting that it was difficult for the meetings to be productive because teachers did not know what they were working toward or if they had accomplished anything. “How do you know if you’re improving if you don’t measure improvement,” she said. “If you don’t establish tracking, you don’t know where you were and you don’t know where you are now….You go on gut feelings and anecdotal evidence.”

Operating without a clear understanding of the goal of the meetings and perplexed and annoyed by some of the methods used by the SF-CESS facilitators, teachers found it difficult to be motivated about participating in the meetings — something that senior Karla Magallanes, who is a student facilitator and a member of the BSU and the Latino cultural club, La Raza, observed and believes was a significant factor in the trainings’ lack of effectiveness. “When we would talk about race or bring up certain things that were about racism in this school or problems like that, it didn’t seem like [teachers] wanted to talk about it,” she said. “It kind of just went silent and that’s why I feel like the meetings never really went as we [student facilitators] wanted them to.”

Berhane, who attended equity trainings on and off for two years, also did not notice improvement when she attended the last equity meeting of the 2018-19 school year. “A lot of [teachers] didn’t really learn as much as they should have,” she said. “What they were focusing on is how can we fix [racial equity] in the classroom and that was just kind of a question they couldn’t answer.”

As dissatisfaction over the meetings continued to mount, looming budget constraints for the current academic year combined with a fee hike from SF-CESS became the impetus for change in the monthly trainings. In September 2019, Lowell negotiated a new contract with SF-CESS that effectively brought the management of the trainings in-house, with SF-CESS providing monthly consultation regarding teachers’ progress and assistance in brainstorming new ideas for the program, according to Beltran.

The monthly meetings now take place in a professional learning community (PLC) format in which teachers have been split into 10 groups, with approximately 20 teachers per group. Each group is facilitated by a Lowell faculty member and discusses a different topic, such as “Equity through Critical Thinking Strategies,” “Equity through Project-Based Learning,” and “Equity through Small Groups and Collaboration.”

Due to budget constraints for this school year, Lowell has taken over much of the facilitation and organization of the equity trainings.

Beltran took the lead in creating this new program. He and principal Dacotah Swett identified teachers they believed would be willing to lead groups and were already using collaborative teaching strategies, such as small-group work, in their classrooms. Beltran then worked with these teacher-leaders to devise a plan for their group meetings for the remainder of the school year.

The goal of these reformatted monthly meetings is to take the equity knowledge gained through the SF-CESS program and to apply it to new teaching practices that are aimed at reaching and impacting students of all races, ethnicities, and backgrounds. “[Teachers were wondering] what can I do now aside from just understanding that there’s racial inequities. And a lot of the problems are beyond teachers and that’s frustrating,” Beltran said. “The idea was we can control what we’re doing here. If we learn these strategies and implement them successfully and appropriately, then it should, in turn, empower a lot of our students of color to perform better in the classroom and feel that they’re part of a community.”

Six months into this reformulation, teachers are welcoming the new approach, particularly having their peers lead the monthly meetings. “I think people respect the time that [teachers] put in to organize the meetings and the fact that we can go and we can learn something from each other,” Christensen said. “When you walk away and you say, ‘That’s kind of good. I learned something today from my colleagues that I didn’t know before’ or ‘I thought about something I hadn’t thought about before,’ that’s always pleasant. It doesn’t feel like it’s forced on you.”

With SF-CESS consultants no longer facilitating the meetings and much of the firm’s restrictive language discarded, Melvin, who facilitates a PLC group, says that teachers feel a new sense of comfort in expressing their opinions and asking questions. “It feels much more productive, which is a win, and much more relaxed. It’s not as judgmental,” she said.

Many Lowell teachers say the transition to PLC meetings this year has resulted in a more welcoming approach to the trainings originally developed by SF-CESS.

Rather than adhering to a strict structure, meetings tend to be more flexible, with faculty members learning new methods of teaching and problem solving from one another, says Melvin.

Beltran notes that he has seen faculty attendance at the PLC meetings increase over the last six months in comparison to the SF-CESS trainings, when some teachers refused to participate.

Despite the positive teacher response, Duru is concerned that the meetings are overlooking the reason the trainings began in the first place — the lack of racial equity at Lowell. “I feel like [Lowell] gave up on SF-CESS,” she said. “In terms of what [Lowell is] doing now, it’s very different from what they were doing the first time I was a student facilitator and I’m not really sure it is that effective because I still don’t see any change here.”

Beltran, however, says that the issue of equity remains at the core of these new PLC meetings. “Equity is still at the forefront, so it’s not like we don’t talk about equity at all anymore,” he said. Beltran ensures that each training begins with an “equity frame” — an activity or group discussion that articulates, through an equity lens, the purpose of the work teachers will be doing that day.

Melvin echoes Beltran’s assurance that racial equity is a significant part of the new trainings, and she says that what matters most is that teachers are addressing equity as a whole. “At the end of the day, as a teacher, what’s important to me is that every student, regardless of their background, regardless of how they come in, regardless of what they’ve got going on, feels heard and learns and is supported,” she said.

Either way, Duru believes that students need to take more responsibility for their actions and begin to take steps as a community toward changing the culture at Lowell. “Students have to step up,” she said. “It should not just be one student who changes Lowell. It should be all the students.”

Members of Peer Resources developed the LRP during the 2017-18 academic year to help resolve conflicts rooted in race, religion, ethnicity, and gender within the school community.

Over the last two years, members of Peer Resources have demonstrated student-led initiative by developing the Lowell Restorative Protocol (LRP). Through LRP, students act as mediators in conflicts that are rooted in race, religion, ethnicity, or gender. The procedure works to address school-wide conflicts and conflicts that occur between students, which often go unresolved. “One of the complaints that we’ve heard over the years and that I’ve heard over the years is if there’s some kind of microaggression and [a student] reports it, nothing happens,” Peer Resources coordinator Adee Horn said. “It kind of falls into this black hole.”

The aim of this protocol is to assist students like Duru, who has experienced this “black hole.” After overhearing the Asian and Caucasian boys in her AP Computer Science class discussing the use of the “N-word,” she reported the incident to dean of students David Beauvais. Citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), Beauvais said he was not able to comment or provide information to The Lowell on the incident. Beyond an initial meeting with the boys, Duru is not aware if any further action was taken.

With mediation being optional and Peer Resources members struggling to find more ways to inform the Lowell community about LRP’s existence, only three conflicts have been brought to the LRP team to date.

Going forward, Beltran says he is planning to devote more time to educating students about racial equity — a seemingly much needed intervention, as 63.3 percent of students surveyed by The Lowell in March 2020 do not believe that lack of racial equity is an issue at the school. “There aren’t any racial problems I’ve heard or seen,” one student responded in the survey. “I don’t think there is a racial equity issue,” said another.

Such opinions demonstrate the dearth of awareness and insight about this topic among the majority of Lowell students — and the need for teachers to diffuse the knowledge they have gained in the trainings to their students. “If teachers model behavior, I think as young students, you see that and follow that model,” Christensen said. “As teachers, if we walk by and hear stuff, we have to stop it…. We can’t just turn our head and say, ‘I don’t want to deal with it’ because we have to educate kids. That’s our job.”

Beltran’s plans include making time at the beginning of the 2020-21 school year for separate class assemblies in which he and other administrators will relate important class-specific information and have a conversation about racial equity with students. “I think that’s a space where we can also say, ‘Let’s have a quick talk about microaggressions, racial sensitivity, cultural appropriation,’” he said.

Beltran acknowledges that these assemblies will not rid Lowell of race-based conflicts, but he thinks that they can help students to be more conscious of their actions and the consequences. “The goal isn’t to not make mistakes,” he said. “It’s to be aware of them and be able to own them.”

I think that some of the problems we have are people come and go, positions change, students change, and so I think there is improvement, but I think we’re looking for it to be immediate and that’s just not going to happen. It’s not the way the system works.

— Orlando Beltran

Duru, Magallanes, and other minority students remain frustrated with the slowness of change and Beltran knows that. He says that it is difficult to enact change with a new class of students joining the school each year and a senior class leaving. “It takes a lot of time,” he said. “I think that some of the problems we have are people come and go, positions change, students change, and so I think there is improvement, but I think we’re looking for it to be immediate and that’s just not going to happen. It’s not the way the system works.”

Beltran asks that students and teachers recognize and appreciate the small changes that have come about at Lowell since the equity trainings began. Since he joined the Lowell administration at the start of the 2017-18 school year, Beltran has seen cultural events grow in size and popularity, including La Raza beginning the tradition of organizing a Day of the Dead celebration and the BSU having an increasing number of students join club members to celebrate Black History Month as part of the annual BSU assembly.

Meanwhile, the monthly teacher trainings in the PLC format will continue next year with possible minor adjustments, depending on the results of the program evaluation Beltran says he will conduct later this semester. The Lowell administration has not decided if it will continue to use the services of SF-CESS next school year.

What is most crucial for Duru is that Lowell continues with efforts to bring issues of inclusiveness and cultural sensitivity to light. “The issue will definitely be forgotten if no one continues to talk about it,” she said. Despite the trials she has encountered, Duru remains hopeful. “With the students here and how diverse the school is, we can do a lot,” she said. “Just integrate, assimilate, and move on with the change.”

Adrian Lee • May 3, 2020 at 6:33 pm

Aloha!

I’m a graduate from the Class of ‘81 and it was great attending a school on the academic cutting-edge of preparing its students for college.

The following excerpt from this fine article represented how I felt during my years at Lowell:

“… 63.3 percent of students surveyed by The Lowell in March 2020 do not believe that lack of racial equity is an issue at the school. “There aren’t any racial problems I’ve heard or seen,” one student responded in the survey. “I don’t think there is a racial equity issue,” said another”

I would have been part of the 63% and I would have been WRONG!

Micro aggressions are something my wife has been educating me on. When people like myself don’t get to experience it first hand it’s hard to explain. Often, the victims of micro aggressions feel like others are gaslighting them.

May I please ask if a mandatory course in racial equality is in the curriculum?

May I also ask how many teachers at Lowell are black?

It’s my hope that Lowell will make large strides in creating a school that’s cutting-edge in racial equity and preparing the students to be more racially understanding of all.